If the social contract is to remain fair, the well-off elderly will need to make a bigger contribution

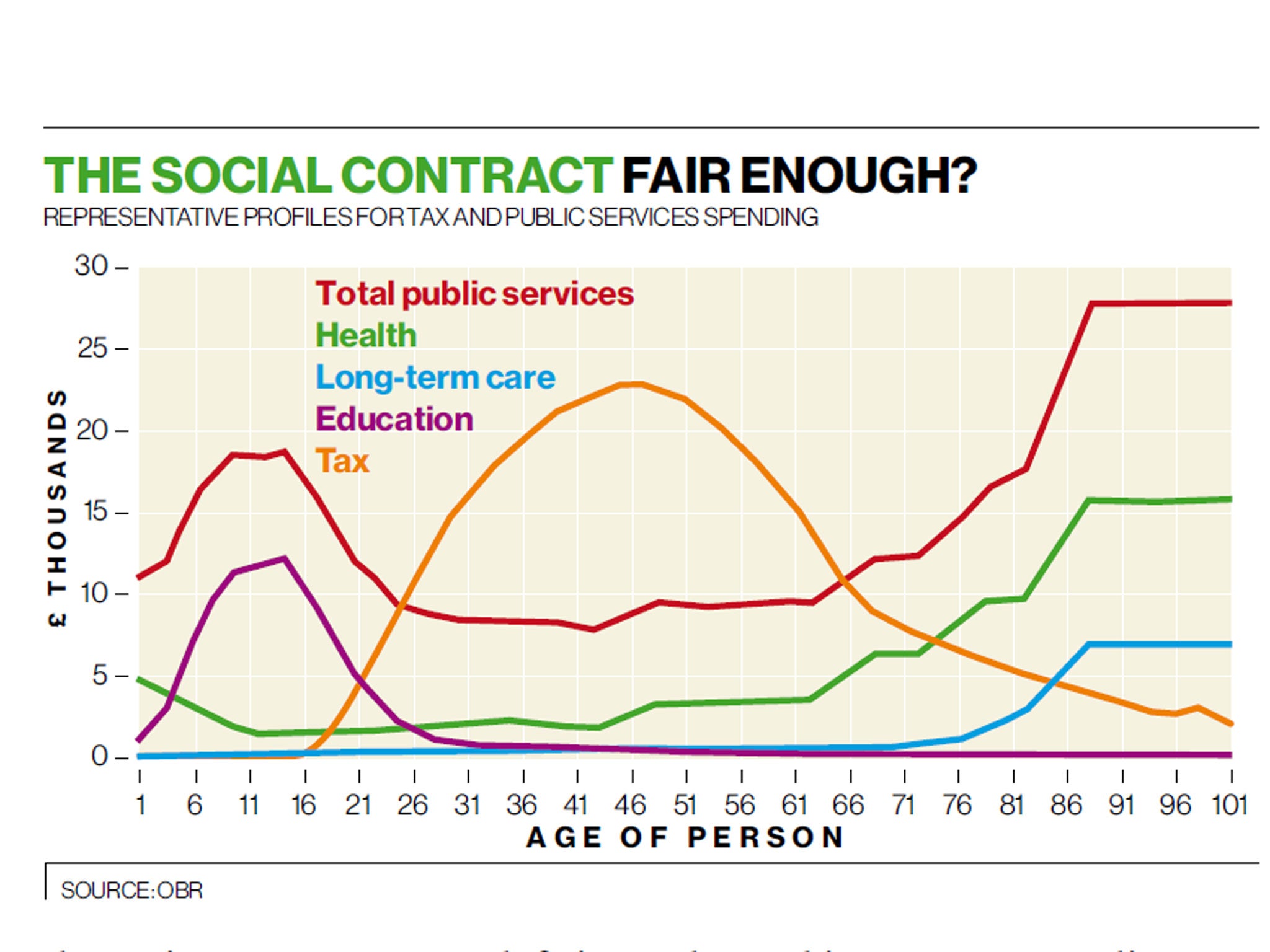

Most spending goes on old people, financed by the taxes of the middle-aged

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The last time the UK economy saw decent growth for more than a few months was the summer of 2010. On that occasion, growth was derailed by a combination of bad luck and bad macro-economic policy, in the UK and in the eurozone.

The result has been two years of economic stagnation. In January 2011, after the government had announced its fiscal consolidation plan, but before it was apparent just how prolonged and painful the eurozone crisis would be, we at National Institute of Economic and Social Research forecast recovery, in the sense of above trend growth and falling unemployment, would begin in 2012.

This was too optimistic — as well as international factors, we underestimated the damage done by tightening fiscal policy too quickly, combined with the reluctance of business to invest in a climate of uncertainty about demand both domestically and internationally. Nor did we anticipate that six years after the start of the financial crisis, Britain’s financial sector would remain largely unreformed.

But it is equally possible that we will underestimate the strength of the recovery. Given the amount of spare capacity — as the regular author of this column, David Blanchflower, has shown, not only is unemployment very high but underemployment is still higher than it was in 2009 — the scope for rapid growth is there. There is no sign of wage inflation, and with the Bank of England pledging to keep interest rates at effectively zero until unemployment does fall significantly, interest rates will not be going up any time soon. Meanwhile, the Government’s effective abandonment of its initial deficit reduction strategy (absolutely the right thing to do) has meant that fiscal policy has been much less contradictory of late.

So the good news is there’s no reason we shouldn’t see sustained, non-inflationary growth for some time to come. However, we’ve seen no sign at all of economic rebalancing. Business investment remains at extraordinarily low levels while the UK’s current account deficit remains high. Growth is being driven by domestic demand, which in turn has been driven by a fall in household saving and by a renewed rise in house prices, which the government’s misconceived Help to Buy scheme risks pushing up further. One risk is that this is unsustainable, and households decide to start saving again. This would pose a short-term risk to consumer demand and recovery; hence Mr Carney’s pledge to keep rates low.

But the other risk is that this low level of household saving is sustained; this would be good for growth in the short term, but over the longer term the UK needs to save more, not less. My predecessor as NIESR director, Martin Weale, now on the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee, wrote in 2005 that the UK was saving less than half of what would be a “sustainable” level. Since then, saving hasn’t doubled — it’s halved.

So what should policymakers do? Making monetary policy contingent on a fall in unemployment probably makes the best of a difficult position. We can’t afford to abort another recovery, even if that means higher house prices and lower household saving than is ideal. On fiscal policy, the priority is still increasing public investment. This remains flat at historically low levels, after the sharp cuts of 2010-11. Increasing it would have both short-term benefits, helping to rebalance the recovery towards investment and employment, and pay longer-term dividends by increasing productive capacity.

Alongside that should go a renewed effort towards tackling youth unemployment. A compulsory jobs guarantee for young people not in education or the labour market, based on the successful Future Jobs Fund (cancelled before the Department for Work and Pension’s own evaluation showed it to be a great success) would be relatively cheap, and good value for money. One thing we shouldn’t worry too much about in the short term is the deficit. I have long argued that talking about another “decade of austerity” is overhyped. As I’ve argued repeatedly, the experience of the 1990s shows that with a few years of decent growth, much of the problem will vanish, as tax revenues rise and some spending falls. If recovery strengthens, we may see some rise in gilt yields but this will be a good sign not a warning.

However, a respite from constant scaremongering about the debt and deficit doesn’t mean that we don’t face serious challenges over the longer term. And it is to these challenges, highlighted by the Office for Budget Responsibility’s recent Fiscal Sustainability Report, that the debate now needs to turn.

The OBR analysis doesn’t say that the UK’s welfare state is unsustainable or unaffordable; overall, it isn’t. But it implicitly highlights a contradiction. The public remains committed to high-quality public services – education, health and social care – provided largely free. But it also remains reluctant to pay the taxes necessary to fund them.

This will intensify: over time, an increasingly affluent society (as, on the whole, we will become) is likely to want to spend more on improving the lives of its citizens, and an older society is likely to want to spend more on the priorities of older people. And, as the chart above shows, most government spending goes on old people (especially very old people), financed by the taxes of middle-aged people in work.

This increased spending can only be financed by individuals directly, or through taxes, social insurance, or cuts elsewhere: it must be financed fairly. If we are not to place an unacceptable burden on those in work — or to cut spending on everything else we want government to do, from providing a good education for children to protecting the environment to building roads — then this has to mean, one way or another, better-off older people, especially those who benefited from the long house-price boom, paying more.

There are lots of ways this could be done — higher property or inheritance taxes, or charges for services, payable only after death for the asset-rich on low incomes – but we need to end the expectation among relatively well-off people that they are entitled both to depend on publicly financed services in their old age and to leave their houses to their children. Ducking this choice will just guarantee a future crisis, fiscal or political.

Jonathan Portes is director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research. David Blanchflower is away

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments