If Labour wants to win again in 2020 it needs to unite and distance itself from the past

Tony Blair didn't go around in the mid-1990s pointing out that Harold Wilson had won four elections

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

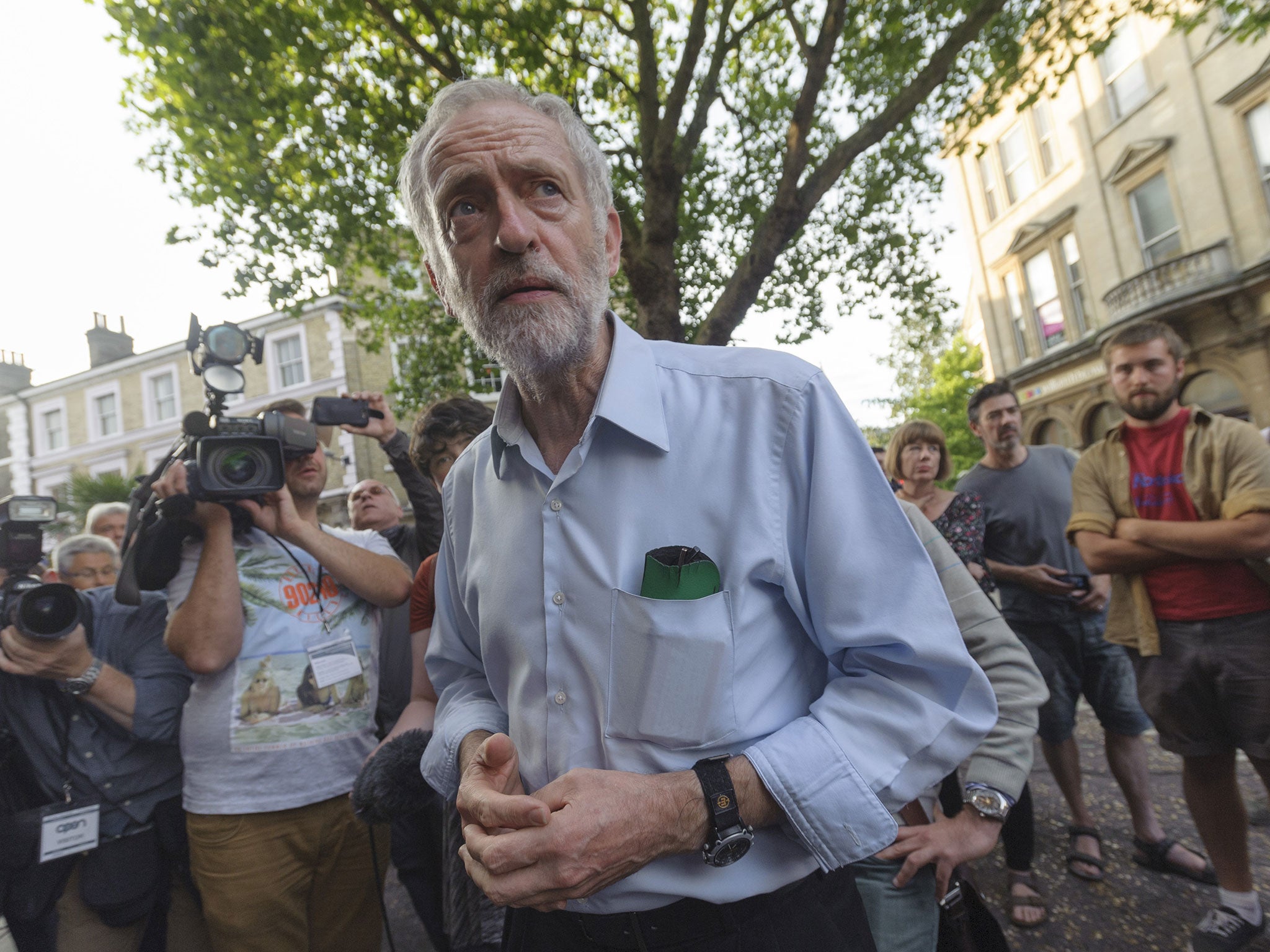

Your support makes all the difference.Leadership campaigns are the moment in politics where individuals appear to matter most. In the case of Labour’s latest election one individual, Jeremy Corbyn, is having a more dramatic impact than any candidate in any contest since 1945. But the power of the individual is an illusion. Political contests are all about the context in which they take place, the precise timing, and the state of the party that is electing a new leader. These explain the rise of Corbyn. Jeremy Corbyn does not explain the rise of Corbyn.

Campaigns that take place in the immediate aftermath of defeat struggle to focus on the next general election. The traumatised party is still getting over what has just happened. Those that take place later are different; the past is a little more distant, the next election closer.

The Tony Blair who won in 1994 could not have done so in 1992 when he toured the studios praising Labour’s campaign in the aftermath of defeat. Margaret Thatcher won in 1975, a year after her party’s first election defeat of 1974. In a fragile mid-1970s hung parliament there was a sense that another general election could follow at any time. In striking contrast Labour’s current contest is the first it has staged in a fixed, five-year term parliament, an overlooked factor in explaining the volatile mood. The next general election seems miles away because it is.

When contests take place priorities surface within parties that are beyond the power of any individual to challenge. The Conservative party did not elect the popular Kenneth Clarke in the various contests in which he stood from 1997 onwards because most members disagreed with him about Europe. They stuck to their beliefs and he stuck to his. Parties and potential leaders must dance together, or not dance at all.

Labour’s current campaign is a reaction to the New Labour era, and more specifically, to how that era ended. Blairite commentators point out that Labour won three elections under Tony Blair as if this provides precise navigation towards the future.

In truth, a modern equivalent of Blair would not have cited the Blair era as persistently as his more ardent admirers do now. Blair did not go around in the mid-1990s pointing out that Harold Wilson had won four elections. He did the opposite, establishing distance with the past. New Labour was itself a reaction to the party’s traumatic defeats in the 1980s, a beautifully orchestrated response. But the seeds of New Labour’s success also led to the downfall of its main, brilliant orchestrators. This is what the current contest struggles to make sense of, the significant triumphs and the ending.

Tony Blair was not an expert on Iraq when he backed President Bush’s war, but he was a world specialist on why Labour lost in the 1980s. One lesson learnt was that a Labour leader had to stand shoulder to shoulder with US presidents. That propelled Blair to spectacular election victories but ultimately led him towards his doom in Iraq.

As another world expert on Labour in the 1980s, Gordon Brown assumed that being close to bankers would give him cover to address issues of inequality. For years the bankers’ shield offered protection, but then the shield clobbered him. The photo of Brown opening Lehman Brothers headquarters in London is one of several that haunt him. More recently, Ed Miliband and Ed Balls both felt that to win last May it was necessary to pretend that they broadly agreed with the Conservatives’ approach to tax and spend. Contrary to mythology, Labour presented the most carefully costed and fiscally cautious manifesto of modern times. They lost.

Into the leadership contest comes a candidate who challenges assumptions that led Labour’s last three leaders towards different forms of political hell. Parts of a party that lived through the trauma of Iraq, the financial crash, erratic public-service reforms and a defeat in May hail Corbyn. Those who cheer him are not indifferent to their party’s fate and are not naive. They have ached for a voice that questions the stifling consensus in England about economics and the role of the state, orthodoxies that terrify Labour leaders into submission, acts of submission that in turn destroy the leaders.

But the ecstatic cheers of Corbyn’s fans are largely cathartic. Those cheering hear words that appear to make sense of the recent past. Their response has less to do with the next far-off election in 2020 and the qualities required in a leader. By 2020 Corbyn will be over 70. He has no experience at the top of British politics. On the basis of his own statements he would not go into that distant election with the manifesto he currently espouses. He points out that Labour is a broad church. To keep the broad church intact Corbyn would have to disappoint those cheering now or preside over some form of schism.

If Labour’s members focus even fleetingly on 2020 and agree with Corbyn about their party being a broad church, they must opt for another candidate. If they avoid the tempting high-voltage drama of a Corbyn leadership, they will need to still feel a sense of historic significance or else lapse into anti-climactic gloom. Yvette Cooper would represent historic change in a different form; the first woman to lead Labour, and one who might have the experience to unite a party more openly split than it has been since the early 1980s. She also refuses to fall into the current media trap in which each candidate must admit Labour’s spending levels made the country uniquely vulnerable during the crash, an act of submission as dangerous as any demanded of leaders in the recent past. The next general election may seem centuries away, but it will arrive. Labour needs sweeping change to have a chance of winning, but first it needs to survive as a broad church.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments