I can’t say Brian Sewell was my friend, but we were allies

It was always comforting to know that in the battle against the architecture establishment I was not entirely alone

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

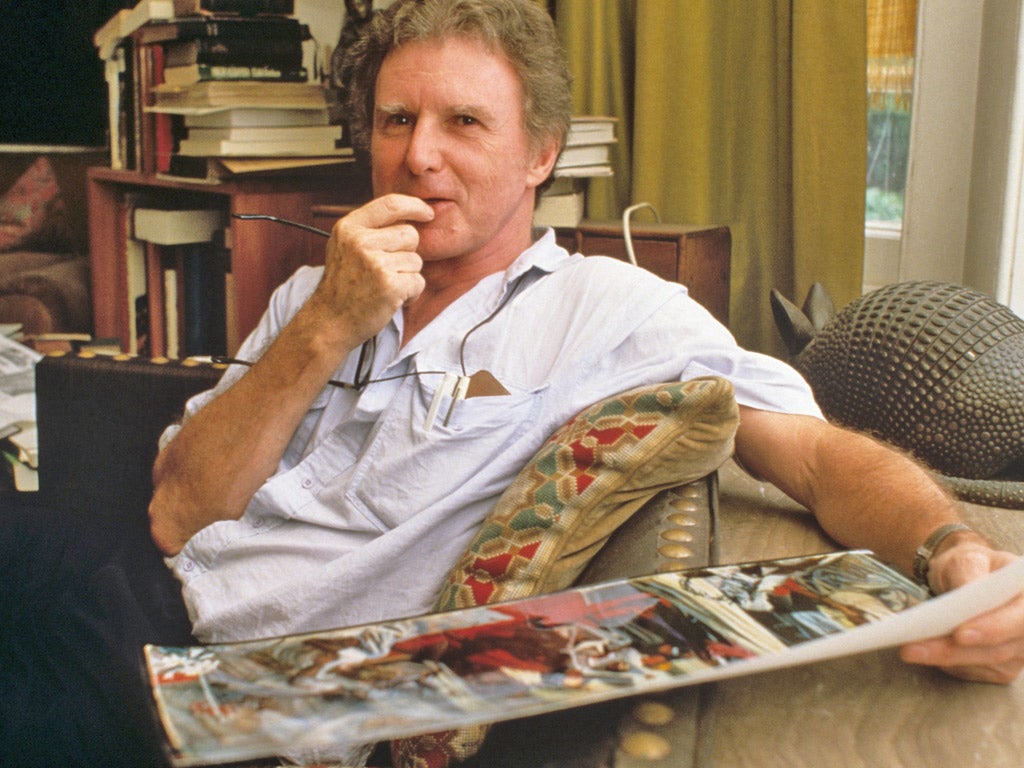

Your support makes all the difference.Did anyone really know Brian Sewell? I somehow much doubt that anyone did – which is probably why, as soon as I heard of his death, my first thought was, “I hope someone is looking after Brian’s beloved dogs.”

I first came across Sewell when he was already at the peak of his work, where he stayed until his death last week. My career at the London Evening Standard was just beginning. It was June 1986 and I had spent an evening at Old Spitalfields, where the discussion soon turned to the proposals to develop Paternoster Square, the bleak and windswept precinct surrounding St Paul’s. We all agreed that the modernist plans by architects Arup were a slap in the face of Wren’s masterpiece.

One of the assembled complainants was John Simpson, a young architect who believed that Prince Charles felt as strongly as we did. I asked him whether he would spend some time drawing up a scheme the Prince would like. When he did I showed it to the Evening Standard’s editor, the late John Leese. He said: “Ask Brian Sewell.” The rest, as they say, is history.

I discovered that Brian’s criticisms of modern art were identical to mine of modernist architecture. I can’t say it made us friends, because that was not his style – or perhaps because I am a woman, a gender of which he did not often speak highly.

Indeed, when he moved from Kensington to Wimbledon after his mother’s death, I invited him to come to my house and meet my Turkish cats. I knew he had a very soft spot for Turkish animals, having rescued Turkish dogs and brought them to this country to dote on. But, after asking twice, while he was nothing but impeccably polite, I realised my invitation was not welcome and desisted. We remained allies, however, and it was comforting to know that, in the (mostly losing) battle against the architecture establishment I was not entirely alone.

One regret I still nurse is that, when an opportunity arose in 1991 for Brian to meet Prince Charles, who held him in high esteem, I was not able to fight off Charles’s “advisers” and courtiers who strenuously objected to a meeting between the two men who lived and worked less than a mile apart. Not that Brian gave it a second thought. At that time he was more interested in the television version of A Question Of Attribution, Alan Bennett’s play about his Cambridge colleague Anthony Blunt – the one-time MI5 double agent, celebrated art historian and surveyor of the Queen’s pictures. The BBC production contained one massive and private example of Sewell’s wit.

James Fox, who played Blunt, spent months studying the aloof, arrogant, condescending and snobbish miser. For hour after hour he mimicked his every mannerism, including the stoop. But the voice – it was the voice of Sewell. That extraordinary voice, which Sewell always denied was unusual or special in any way, even though he later made use of it for advertising voiceovers.

But, as he told us in the office, after the play was broadcast to much acclaim: “Blunt didn’t sound anything like me. It was a bit of a joke between Bennett, Fox and me. He studied my voice and used it. Most people thought I had copied Blunt’s way of speaking – not a bit of it.”

I hope you find peace wherever you may be Brian – and I hope you meet all your dogs there.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments