Hiroshima 70th anniversary: The past can be forgiven here, but it will never be forgotten

Once a year, elderly survivors must relive the most excruciating experiences of their lives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is impossible to conjure up the agony visited upon Hiroshima’s 70 years ago as you walk around the rebuilt city, with its airy shopping centres and tree-lined boulevards.

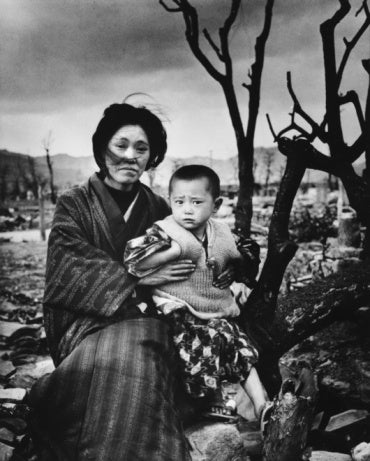

Photos of the vaporised city taken in August 1945 are poor, grainy substitutes. The main conduit to the past is through the memories of the atomic-bomb survivors.

Once a year, elderly hibakusha (survivors of the bomb) must relive the most excruciating experiences of their lives. Their stories become numbing: people blown away like flecks of dust; children dying as they screamed for mothers who had been incinerated; the dangling eyeballs, burst intestines and mutilated skin of neighbours and friends; the stench of burning flesh and death in the summer heat.

Sakue Shimohira, 80, has told the same story in thousands of speeches: finding her mother turned to charcoal, and how when she touched the corpse it disintegrated; her brother dying in agony days later, his body wracked with vomiting and bloody diarrhoea, the symptoms of the then-unknown radiation poisoning. “He kept saying: ‘I don’t want to die.’”

Terumi Tanaka tells me how as a 13-year-old boy he helped cremate much of his family before the end of August; of witnessing ponds and rivers filled with bloated corpses, the survivors sitting blank-eyed, their wounds filled with maggots. “Nobody wants to remember such things but we do because we want people to know the truth,” he says.

“These are people who lived through the worst hell imaginable yet they’re not bitter and they don’t want revenge,” explains Peter Kuznick, a history professor at American University who brings his students every year to Hiroshima. “They want to use their experience in a positive way to build world peace. It’s such a powerful message.”

Official Hiroshima cultivates this message, with its museums, memorial parks, peace boulevards and the iconic, hollowed-out Dome. In August, schoolchildren stage “die-ins” beside the dome, replaying the events of 70 years ago. As I watched, the sound of John Lennon’s “Imagine” wafted from a speaker across the river.

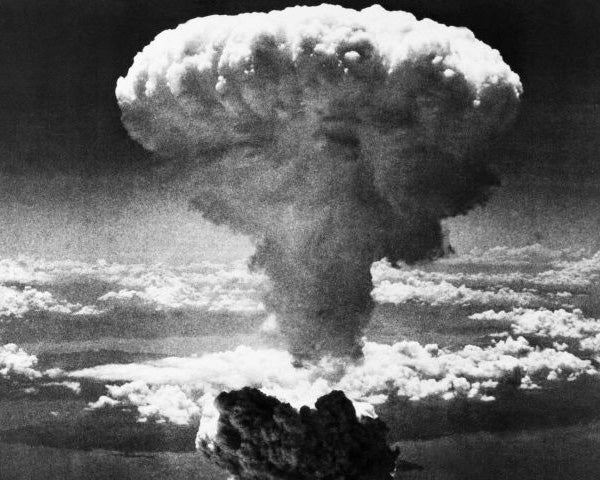

Survivors have made thousands of pilgrimages to the US to lecture on what happened beneath the twin mushroom clouds of August 1945. Many Americans still have little idea of the horrendous human cost of the bombings because they have been told that they saved lives and ended the war, says Mr Tanaka.

But America is not alone in being accused of sanitising the past. For many Asians, Hiroshima is a talisman for selective pain. The Japanese paid into the bank of suffering with the atomic bombing and they’ve been withdrawing ever since, whitewashing the suffering they inflicted on others in their schools, history books and popular culture.

Writer Ian Buruma calls the city the centre of “Japanese victimhood”. “It has martyrs, but no single god. It has prayers and it has a ready-made myth about the fall of man.”

China is particularly sensitive to Hiroshima’s status: earlier this year, it blocked Japan’s attempt at a UN disarmament conference to extend an invitation to world leaders to visit the A-bombed cities. Japan, said Chinese delegates in a familiar refrain, was again trying to portray itself as a victim and not the victimiser.

Most hibakusha reject this narrative of selective pain. They are among the fiercest critics of attempts by Japan’s government to rewrite history or water down its commitment to pacifism. It is telling that in polls, the percentage of Japanese who describe the bombings as “unforgivable” is higher nationwide than in Hiroshima, where most appear to have forgiven – but not forgotten.

Forgetting the past puts Japan on the road to war again, says Shoji Sawada. He was forced to abandon his mother to the fires that blazed after the bomb. “I was 13 years old,” he recalls, his face blank. The least he can do, he says, is remember her and speak up about what happened. “It’s what she would have wanted.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments