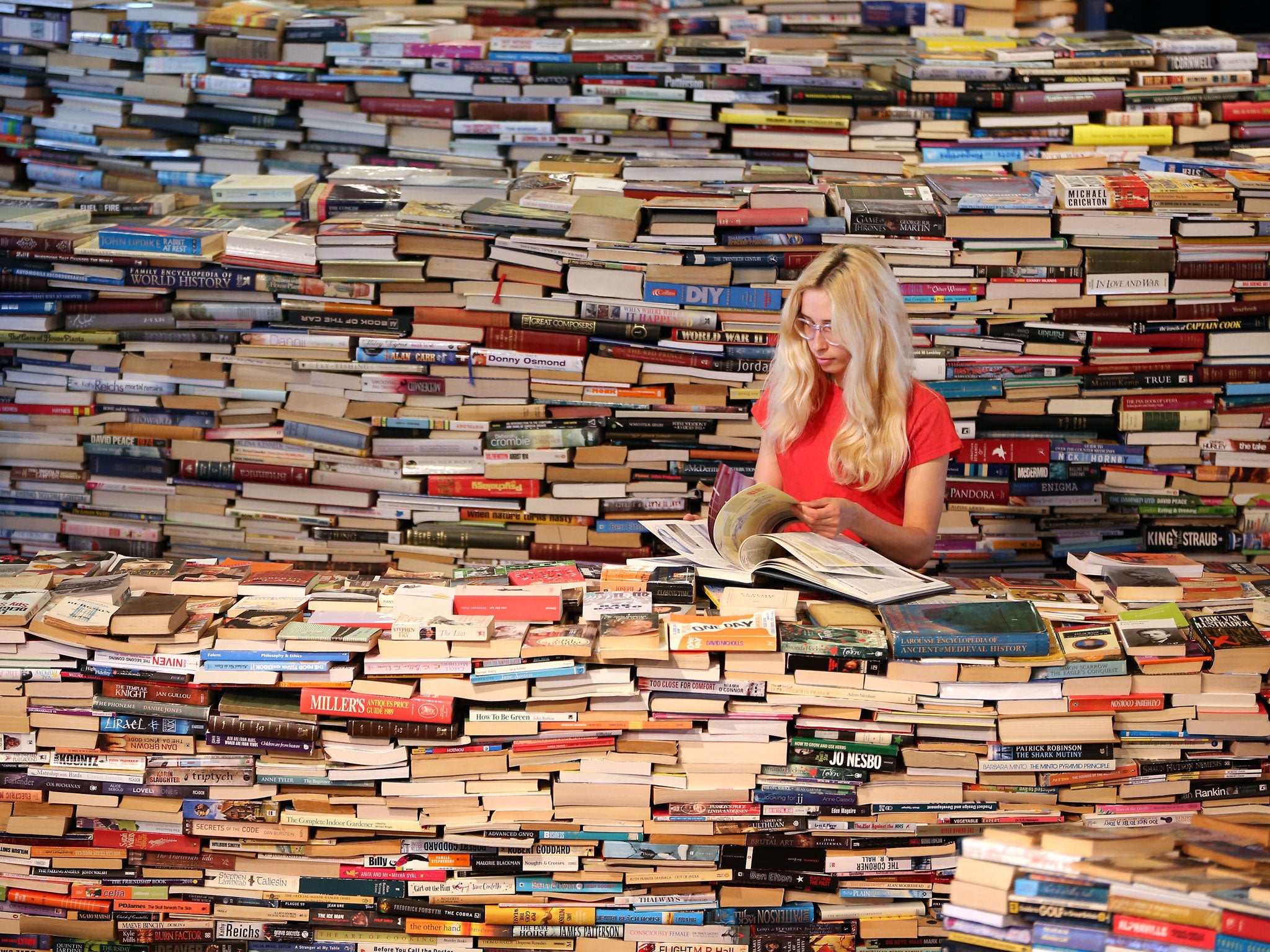

Granta's once-a-decade list of rising novelists is more important than ever

In an increasingly crowded book market, this list of Who will be Who matters to readers because, on the whole, it has got things right.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The year 2013 is partly going to be one of anniversary celebrations – Verdi, Wagner, Britten. But more interestingly, it’s going to be a year when we’ve found a way of looking into the future of creativity, too. The literary magazine Granta is going to produce its once-a-decade list of British novelists under 40. It will be the fourth one since 1983, and just now a generation of hopefuls is quaking in its boots. It matters; it genuinely matters; and it matters because, on the whole, this list has got things generally right.

Before 1983, the promotion of novelists was a haphazard, gentlemanly sort of affair. A publisher might recommend a young novelist to a literary editor, they might acquire a readership, an interview or two might take place, and a small lecture tour of foreign parts, sponsored by the kindly British Council. Literary festivals and creative writing courses were foreign curiosities; the Booker Prize, until very recently, used to be that thing that Olivia Manning always got so cross over not winning.

The wonderfully named British Book Marketing Council, at the turn of the 1980s, had the bright idea of packaging up the best living British writers for promotion, regardless of age. The result was very distinguished, but perhaps not terribly sexy – John Betjeman, Laurie Lee, V.S. Pritchett turned out. It had some effect – I remember reading a very superior article in The Sunday Times, laughing at readers who routinely confused Gerald Durrell (not listed) with his brother Lawrence (listed). At 15, that would have been me.

In 1983, the Council teamed up with the tyro magazine Granta, and produced what undoubtedly was a sexy list. It made the radical decision to limit the list to novelists under the age of 40 – not new novelists, but ones who were born after 1943. That has always seemed arbitrary to me. Many great novelists don’t get started until middle life. One of the greatest of modern British novelists, Penelope Fitzgerald, didn’t start publishing until she was 60. Women, in particular, have often found children delaying their writing career.

Still, it took the imagination of a reading public. It did so not through hype, but because the judges of the 1983, 1993 and 2003 lists have been proved to be excellent judges of talent. (OK, declaration of interest – I was on the 2003 list, though whether I’v e since fallen into the ‘fulfilled’ or ‘sad let-down’ categories is for someone else to say.) Many of the names on the lists were not, at the time, in command of the huge readerships and critical acclaim that subsequently came their way. Rose Tremain, Kazuo Ishiguro – the author of only one novel at the time – Will Self, Monica Ali, Hari Kunzru and others were identified when they were not easy or popular choices. Notoriously, one journalist remarked of the 1993 lists, “But who is Louis de Bernières?”

Of course, there are some names on all three lists who didn’t fulfil their talent, or who haven’t so far. But it’s difficult to find one who was identified for no good reason. Ursula Bentley, from the first list, didn’t become a famous novelist before she died in 2004, but the novel that put her on that list, The Natural Order, is a perfect joy. More problematically, the lists have undeniably failed to identify some major talents; the power of the Granta imprimatur has meant some very good writers have had a harder path in life. It has, undeniably, its biases away from genre and popular novels. Douglas Adams could and should have been on the first list, Sebastian Faulks and Robert Harris on the second, China Miéville on the third, and maybe even J.K. Rowling, too.

It has, though, avoided the overvaluing of “significance” which has made the Booker, in recent years, such a poor identifier of literary value, let alone literary promise. The judges have seemed to enjoy brio, schwung and pizazz, and, mirabile dictu, comedy in whatever shape it comes, whether Martin Amis, Helen Simpson, or Nicola Barker. Brio, unlike the decision to write a long dull novel about a historical genocide, is a quality that tends to last. What is great about these lists is they successfully identify writers who, at the right age, are exulting in sentences, literary form, and even individual words, not ones who think, like any boring blog writer, that they have something to say.

Last time round, I thought there were probably 10 names that would have gone without much debate, and another 10 that might have been them, or someone else entirely. After 10 years, I think the panel got much more right than wrong – well, I would say that, and I’m very grateful for the boost, but I couldn’t name 10 authors who should have been there and were snubbed.

This year, it’s much the same. There are 10 names who I’m sure are already there, and 10 who are going to be fought over. My 10 dead certs are Jon McGregor, Zadie Smith, Ned Beauman, Ross Raisin, Joe Dunthorne, Sarah Hall, Adam Foulds, Samantha Harvey, Nick Laird, and Paul Murray. The next 10, I guess, will be Stuart Neville, Naomi Alderman, Evie Wyld, Neel Mukherjee, Courttia Newland, Tahmima Anam, Owen Sheers, Helen Walsh, Alex Preston, and Gwendoline Riley. I think the judges will pass over A.D. Miller and Stephen Kelman, relics of the worst Booker shortlist ever in 2011, and generously reward a novelist whose first novel still sits in typescript, unknown to you or me.

The accurate gaze forward is what the judges have to embody; it’s been done before, but it’s going to be quite a challenge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments