George Osborne's latest flop over 'shares for rights' is typical of modern government

Since it became law the Department for Business has received only four inquiries, but this measure's history says a lot about the replacement of ideology with marketing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

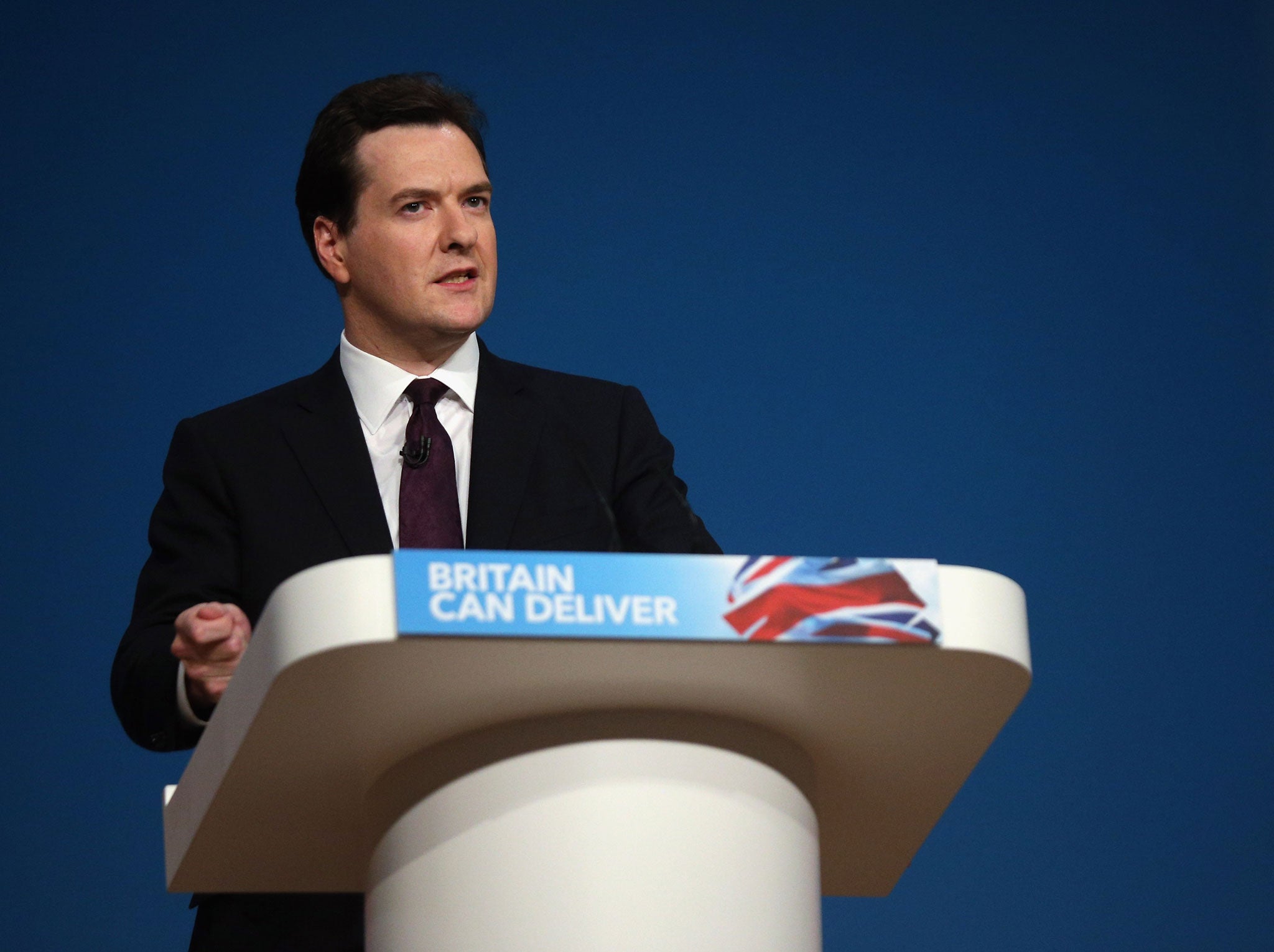

Your support makes all the difference.It was the lead story in the Financial Times on Saturday: “Osborne shares for rights plan flops”. Yet when the Chancellor of the Exchequer first announced that employees could be given shares in the businesses they work for in return for giving up their employment rights, he was lyrical in describing his proposals. He introduced them at the Conservative Party Conference in Birmingham last year in language that counts as uplifting on such occasions. Mr Osborne told delegates that “we will be the Government for people who aspire. Our entire economic strategy is an enterprise strategy”. And so on.

Here is the deal as he explained it. “You the company: give your employees shares in the business. You the employee: replace your old rights of unfair dismissal and redundancy with new rights of ownership.” And we, the Government? We will “charge no capital gains tax at all on the profit you make on your shares.” Then George Osborne seemed to make fun of himself, or perhaps of the Prime Minister, with his Big Society ideas: “owners, workers, and the taxman, all in it together,” he added.

However just five minutes’ thought would have been enough to show that this was a pretty stupid idea. How exactly would employees value the rights they were being asked to give up? Wouldn’t they smell a rat? Would they not think that they would be done out of their employment rights when they most needed them, in return for worthless shares? And would the typical, medium-sized enterprise, with shares tightly held and rarely traded, want the bother of making a new issue? Just completing the documentation would be a formidable task. Worse still, it quickly became apparent that the scheme could open the door to fresh tax avoidance opportunities. As Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, commented: “Just as Government ministers are falling over themselves to condemn such [avoidance] behaviour, that same Government is trumpeting a new tax policy which looks like it will foster a whole new avoidance industry.”

Then, when the Government asked 209 businesses last year for their comments, only five gave their full support. Yet despite this disappointing response, ministers pressed on. And now it turns out that since April, when the plan became law, the Department for Business has received only four inquiries and HM Revenue & Customs just two. What a flop! It’s not going to fly. The relevant clauses in the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 will scarcely ever be used.

The history of this minor measure says a lot about the quality of Government. What was the attraction of the scheme to Coalition ministers in the first place? As an unexamined notion, it perhaps seemed a good idea that workers should own shares in the companies for which they work. In particular, as one official remarked, ministers had in mind “innovative new start-up businesses that are keen to grow and to share ownership”. I believe quite the reverse. It would be foolish to trade away your redundancy rights in return for shares when there is any risk of your company going out of business. You don’t want to lose part of your savings at the same time as you lose your job.

A second factor in favour of the scheme must have been that it was anti-union. But is trades union activity really a problem for the British economy at the moment? Only, I would say, where trades unions have obtained a blocking position on certain public services such as the London Underground. Otherwise not.

So how should the Government have proceeded? Before making an announcement at a high-profile occasion like a party conference, it should have carried out research to discover whether the proposals had merit or not. This begs the question, what is “merit”. My answer would be that the plans would have merit only if they were likely to contribute either to economic growth or to fairness.

As far as one can see, the Government did none of these things (and there is a reason for this that I shall come to). They are such elementary preparations for any sort of policy making that they could well be taught at school. But there was still one final step to take. Before going public with the new initiative, the Government should have undertaken some user testing. Actually it did this when it asked the 209 businesses what they thought – but by then ministers had already made up their minds. So that was a charade. And as to questions of merit, my assessment is that swapping employment rights for shares would contribute infinitesimally to growth and zero to fairness.

What I have described is contemporary politics. I compress the basic rules. They are these. Ideology has gone. There are no differences of principles between the three main parties, only of emphasis. So general elections provide a choice between rival teams of political personalities rather than between ideas. These contests last not the statutory three weeks before polling day, but the entire space between elections. They are marketing battles, no better nor worse than the tussles between, say, rival brands of beer. In this context, only headline-grabbing announcements count. Say it loudly and clearly to an adoring party conference. Only when the applause has died away, do the work and pick up the pieces. The announcement is all that matters.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments