From Leveson to Jimmy Savile: our love for public inquiries is more about entertainment than truth

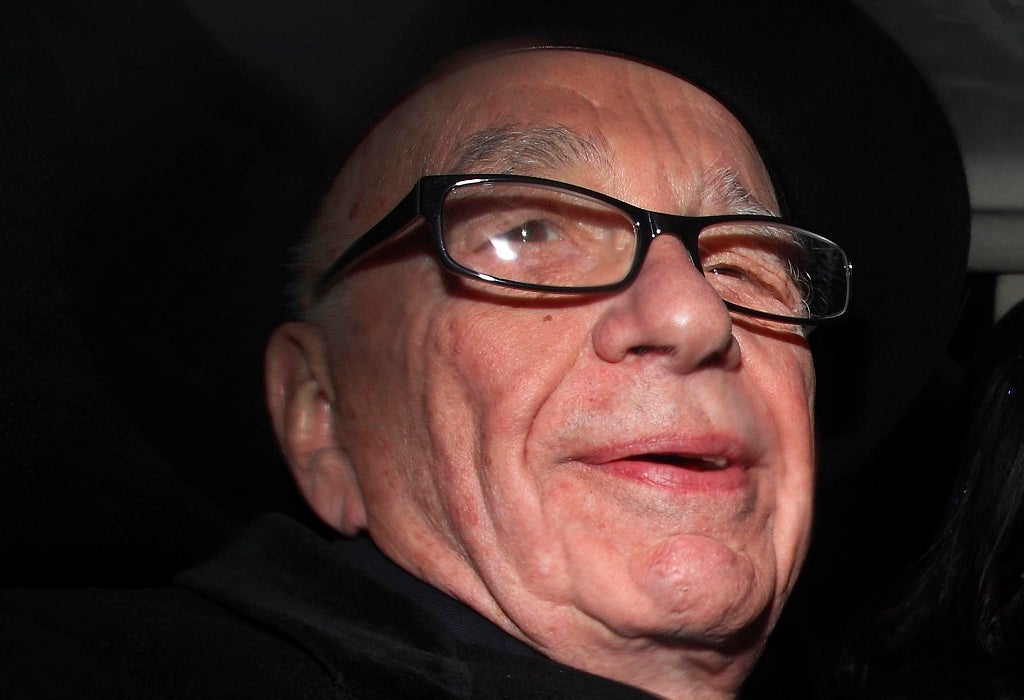

Figures like George Entwistle, who are not made for television, can appear weak and indecisive when they are merely being honest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.During those rare interludes when a public inquiry is not on daytime TV, it is instructive to look at clips from the House Committee on Un-American Activities of about six decades ago, when it was under the chairmanship of Senator Joe McCarthy.

The focus of the respective investigations may be different – banking, journalism and Jimmy Savile take the place of McCarthy’s search for “Communistic activities” – but there are unmistakeable similarities in tone.

A powerful atmosphere of social disapproval attends the hearings. Questioning can be showily aggressive and sanctimonious. Sometimes it can seem as if discovering the truth is secondary in importance to humiliating the person under cross-examination.

No one could deny that inquiries, judicial or parliamentary, can make for great TV. Suddenly the highly paid, privileged people who are normally well protected in their position within the establishment are made gloriously vulnerable, like schoolchildren summoned to headmaster’s study.

We have become sophisticated at watching these new Courts of the Star Chamber, and know every move: the faltering voice, the swivelling eyes, the general air of clammy panic of someone whose argument – whose career maybe – is disintegrating before the delighted eyes of the nation.

Every alibi (“I’m afraid I don’t recall”) and trick (“May I first of all apologise…?”) has been heard before. Our champions, the MPs and lawyers, take pleasure in their new and somewhat surprising role.

On Twitter, a good gauge of people’s moods as they happen, the tone of viewers is gloating and unkind. Seeing the powerful appear foolish and guilty has become a favourite national pastime.

Politicians, too, like nothing better than a well-marketed inquiry. For years, they were the ones on the naughty step; now they can smugly and self-importantly express public outrage to vote-winning, career-enhancing effect.

What the McCarthy hearings showed, though, was that, in a febrile atmosphere of paranoia and moral panic, the truth tends to become skewed. As the broadcaster Ed Murrow said at the time, congressional committees could be useful but there was “a thin line between investigating and persecuting”.

Such is the pressure, the charged atmosphere, which now attends inquiries that it affects the way evidence is given. Some public figures are strong and arrogant enough to show little respect to proceedings (the Daily Mail’s editor, Paul Dacre, before Leveson was an obvious example), and their cheerful truculence carries the day.

Others, most recently George Entwistle this week, can appear weak, timid or indecisive when they are simply trying to be honest. On this type of reality show, the blusterers fare better than the mild-mannered.

Televised inquiries fuel public cynicism, and sanction a new form of bullying. Their popularity has as much to do with retribution and entertainment as with any search for truth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments