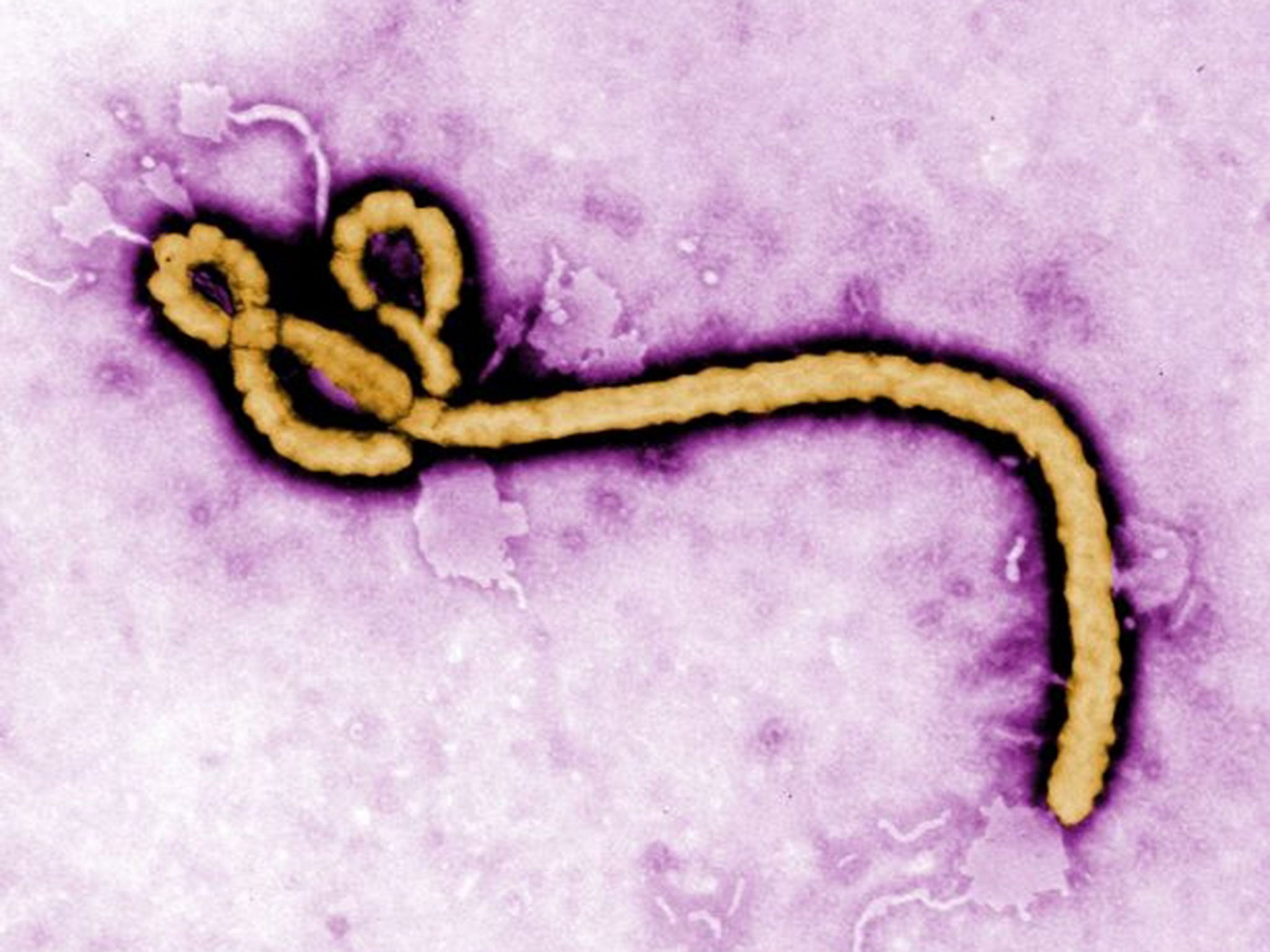

Ebola is inspiring irrational fears that are potentially more damaging than the disease itself

We need to look beyond the stigma that attaches to those who have been infected

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For the British health worker infected with ebola who may be evacuated from Sierra Leone back to the UK as early as Monday, there are only hopes and prayers. There is no proven treatment for the disease. Supplies of the experimental drug ZMapp used on two American victims are exhausted, and the drug may anyway have prolonged their illness rather than made them better, according to the infectious disease specialist who treated them.

As he fights for his life, the health worker – who is employed by the World Health Organisation (WHO) - deserves our gratitude for his selfless dedication. Instead his return may spark fear. That would be an ignorant and foolish response.

Preparations have been made to fly him into RAF Northolt and transfer him to a specially equipped isolation unit at the Royal Free Hospital in north London, so the risk of him transmitting the virus within Britain is extremely low.

The ebola virus is spread via bodily fluids – blood, vomit, diarrhoea - and transmitted by touch (unlike flu which is an airborne disease). If you don’t touch, you won’t be infected. Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, has said he would be prepared to sit next to an ebola patient on the Tube.

But what of the impact on the British victim’s colleagues who remain in Sierra Leone? We do not know how he came to be infected. There may be a straightforward cause – an accident with a needle used to take blood, perhaps – so measures can be taken to prevent it happening again. If not, it will add to the fears of those doctors and nurses who continue on the front line against the disease. They will wonder who is going to be next.

This is rational fear. It may even be helpful if it causes health workers to redouble their efforts to protect themselves. The fundamental rule on ebola is: don’t touch. But health workers must touch – to take blood for tests, administer fluids and antibiotics and provide the supportive treatment that can help patients survive. Hence the need for rigorous protection – gloves, masks, body suits – and immense care over the disposal of corpses and contaminated materials.

The bigger danger is the irrational fear which has infected families, communities, towns and cities across West Africa. As the virus has spread so have wild rumours about its cause, which have been variously attributed to witchcraft, a Western plot, and a conspiracy by African governments said to have introduced the disease in order to extract multi-million pound payments in aid from the West.

Irrational fear is posing as a great a threat to the countries affected as the virus itself. In Liberia and Sierra Leone, the two worst affected countries, hospitals and clinics have closed, leaving patients with other diseases such as malaria with nowhere to go for treatment. The official toll of 1,427 deaths and 2,615 cases in Guinea, Liberia, Nigeria and Sierra Leone is certain to understate the real total, as many people with ebola in rural areas will have died and been buried without their ever reaching hospital. But even the real figure is likely to dwarfed by collateral deaths caused by the collapse of the countries’ health systems.

A clinic and quarantine centre in Liberia’s capital, Monrovia, was attacked a week ago and 29 suspected ebola cases fled while an angry mob looted medical items, instruments and soiled bedding. They were heard chanting that ebola was a hoax by the Liberian president to get money.

At least 129 health workers have died fighting the current outbreak, according to the World Health Organisation. Yet instead of receiving gratitude for their dedication and courage, many have been ostracised and driven from their local communities.

Josephine Sellu, deputy matron in charge of the ebola nurses at the government hospital in Kenema, Sierra Leone, which lost 15 of its nurses to the disease before they were trained in how to protect themselves, was herself threatened by the remaining nurses. “If one of us dies again, prepare yourself to die,” she was warned.

Now a more rigorous system for testing and holding suspected patients has been instituted with international help, and confidence among the nurses has been restored.

But the stigma remains. Her staff had been abandoned by their husbands and shunned by neighbours, Ms Sellu said. One nurse returned home to find her belongings in a suitcase on the pavement. Another looking for a place to rent had to lie to her landlord telling him she was a student.

The impact on the economies of the affected countries – Liberia is reported to be facing 30 per cent deflation - may in the long term cause the most damage. Airlines including British Airways have halted flights despite advice from the World Health Organisation that travel restrictions were not necessary. Cities have been locked down and placed in quarantine, businesses have closed, and farmers who account for two thirds of the working population have abandoned their fields, threatening food shortages. There are fears that the panic caused by ebola could damage the entire continent’s economic revival.

To be afraid of ebola, a lethal disease with a death rate up to 90 per cent, is understandable. The challenge facing West Africa, and the world, is to respond effectively to the threat whilst vigorously confronting the irrational fears that may otherwise multiply the harms it causes and inflict even more pain, suffering and economic damage than the virus itself.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments