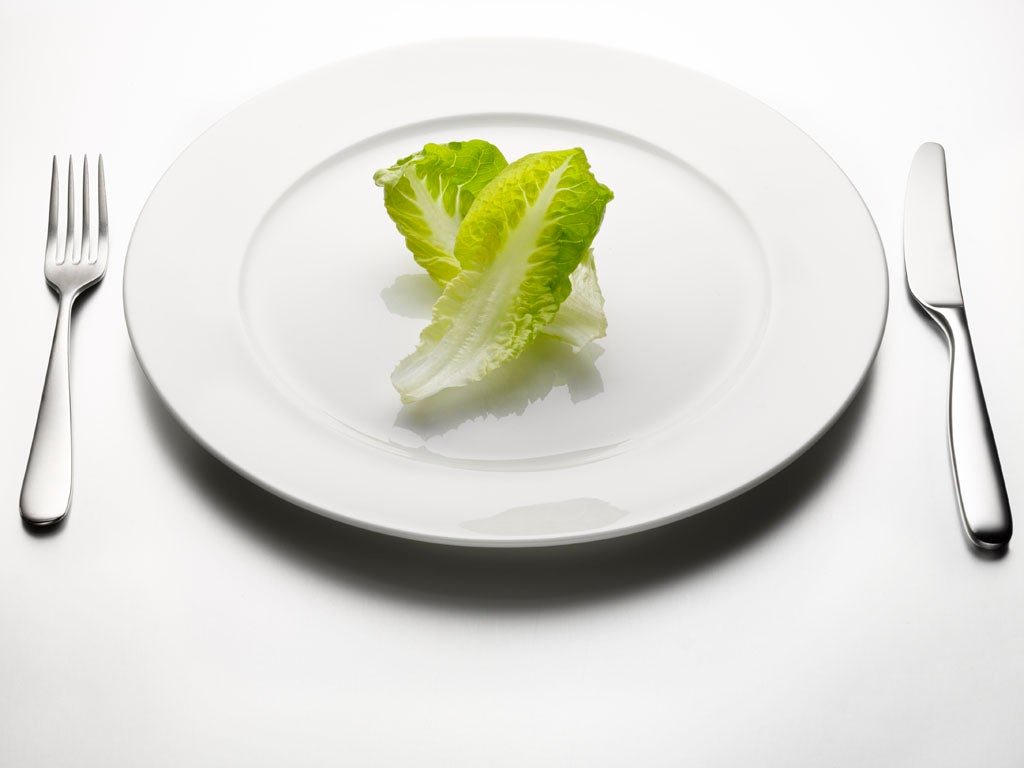

Eating Disorders Awareness Week 2014: you can be too obsessed with ‘healthy’ eating

Many young people are confused about what constitutes ‘health’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I began teaching body image lessons in schools in 2007. Back then, teenagers were pretty much exclusively concerned with the aesthetics of the body. Over the past few years, however, I’ve seen them become focussed, almost to the point of obsession, on the notion of ‘health’.

On the face of it, this appears to be progression. Except most young people’s ideas about what constitutes health are not only woefully skewed, they’re also being encouraged by certain sectors of the medical community, the media and industries intent on selling them potentially dangerous ‘health’ products.

In my experience, most teenagers believe that health can be assessed by factors like weight and body shape. When I ask them how we know if we are healthy, they will invariably suggest hopping on the scales or looking in a mirror, rather than consulting our lifestyle choices.

Physical education teachers tell me it is now widely accepted for young men aged 12 and over to use protein shakes and the lurid, liver destroying powder kreatin to ‘help them perform’ in competitive sports. Boarding house mistresses confessed to me last week at a conference that their female pupils were ordering ‘herbal’ tablets designed to promote weight loss over the internet and, when confronted, were arguing that they were ‘natural’ and that the endeavour was being undertaken in the name of ‘health’.

There appears to be no concept of moderation – going to the gym is considered ‘healthy’, no matter how obsessive or time-consuming the habit becomes. Eating any type of sugary or fatty food is universally dubbed ‘unhealthy’, no matter how much mental anguish and social exclusion the act of refusing that food might cause.

In school canteens, I now routinely hear teenagers claiming to be ‘allergic’ to wheat, dairy, gluten and sugar, or to be embarking on ‘raw, vegan’ diets they have seen espoused by celebrities in the pages of glossy magazines.

Well-meaning ‘nutrition’ lessons, which are given to primary school children as young as five, present health as a black and white issue, attaching moral judgments to basic biological functions: Fat =BAD, thin =GOOD. Biscuit = BAD, fruit =GOOD. Our children are being set-up for a lifetime of anxiety and food and body issues. Ironically, we’re sowing the seeds of shame and guilt which form one of the primary factors behind binge-eating related obesity.

This week is Eating Disorders Awareness Week in the UK. ‘Orthorexia’ – a media-created term meaning ‘obsession with health’ – is growing, with some bloggers arguing over whether it is the newest eating disorder or merely a social trend. Susan Ringwood, Chief Executive of the charity B-eat, however, believes it is more complicated than that. She says:

“The link to ‘ultra-healthy’ eating and exercise habits as a means of adopting a highly restrictive diet is part of a cultural context, as I see it. It used to be vegetarianism, then veganism, and now it’s the issue of food purity. It’s a growing part of the spectrum of eating disordered behaviour, because it’s now culturally acceptable to say you are down the gym every night, or intolerant to wheat, or only eat raw food.”

So our culture of ‘health’ can, in some respects, be viewed as a new way of approaching an eating disorder. This is in the same week that we hear B-eat calling for changes to diagnostic criteria for more traditional eating disorders because these mental illness are STILL being measured by some GPs in stones and pounds. It appears that mental health, which is easily as important as physical wellbeing, is still consistently being pushed aside in the pursuit of a socially-acceptable body type.

The Health at Any Size (HAES) movement, which has taken the US by storm, is now taking root in the UK. Advocates (rather sensibly) claim that if we eat all food groups (paying special attention to consuming five fruits and vegetables a day), make sure we engage in regular physical activity (but not obsessively), drink enough water to stay hydrated, do not smoke and drink alcohol within the recommended guidelines then we are healthy, regardless of how we might look.

It isn’t particularly groundbreaking or glamorous, but it seems this old-fashioned advice of the sort your Nan might have given you is the true path to physical wellbeing, and this is what young people need to hear.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments