David Cameron's response to refugee crisis is mainly about keeping the Tories united

Fragile, narrow-minded expediency is playing a key part in the PM's calculations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

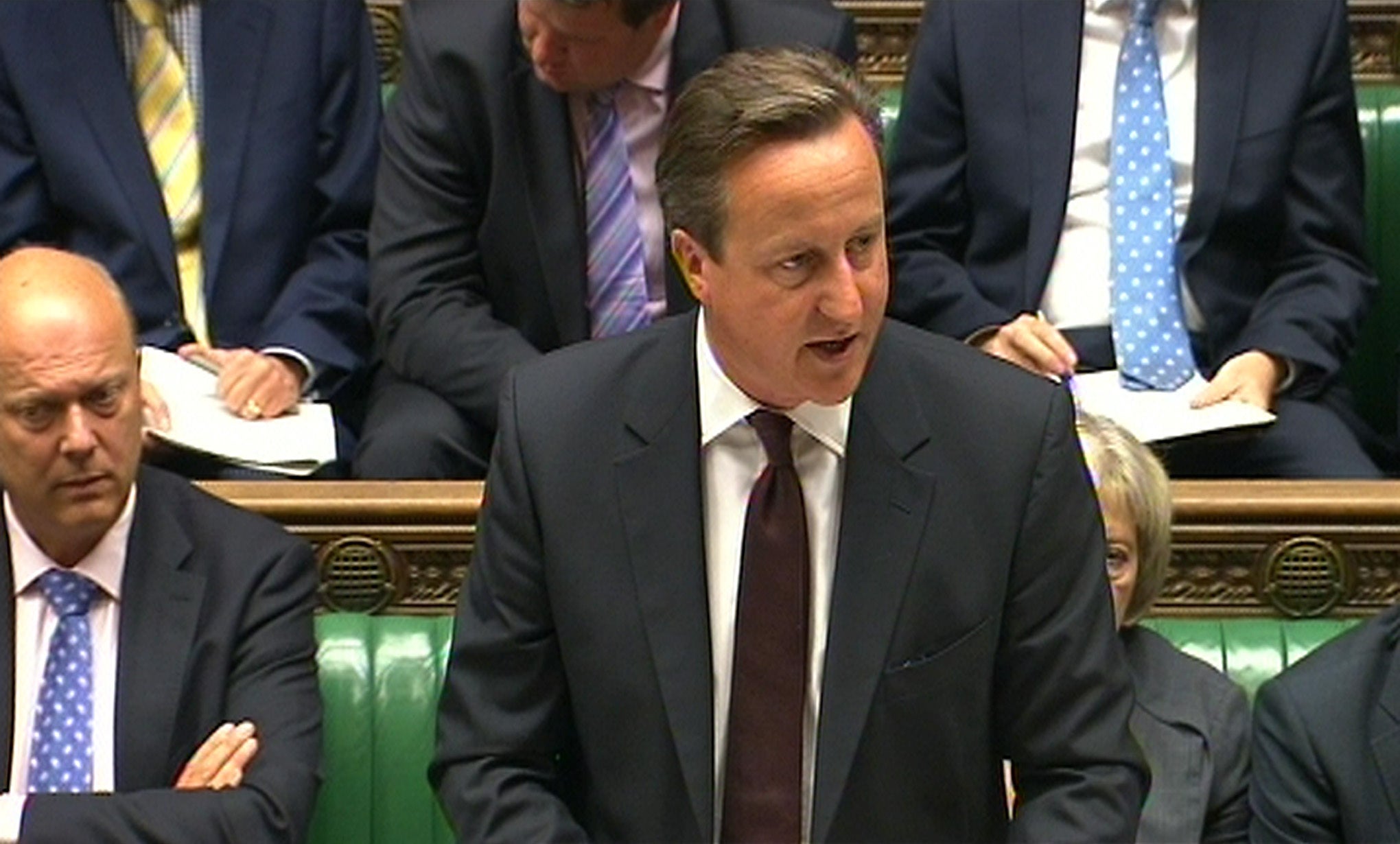

Your support makes all the difference.I had expected to write about David Cameron’s dramatic U-turn on the refugee crisis, reflecting on how a single photograph of a dead child and the emotional response had propelled a Prime Minister into a sweeping change of policy. Instead, what is more striking after his statement to the Commons yesterday afternoon is the degree to which Cameron has stood his ground.

Yes, the government will take in many more refugees from camps near Syria – but over the course of a parliament. No, the Government will not co-operate with others in the EU who seek to reach an agreement on quotas of refugees already in Europe. Yes, the government will make resources available to local councils and other agencies in order to accommodate the additional refugees. No, the government will not spend additional cash, but instead will revise radically the priorities for the overseas aid budget. This was not a U-turn, but what Tony Blair would have called a “third way” between Cameron’s original approach and his need to respond to the media and public demand for action.

Cameron’s response shows both how strong and weak he is since his victory at the election. Had he still been a leader of a coalition, I suspect the Liberal Democrats would have insisted on a more immediately generous response to the refugee crisis, and one delivered earlier than yesterday afternoon. The former cabinet minister, Vince Cable, insisted that would have been the case in an interview this weekend. Freed from such constraints, Cameron has moved in only a limited way after the highly-charged onslaught of recent days. It suggests a confidence that he can stick more or less to what he believes to be the right course, rather than the one suddenly being demanded of him.

At the same time his actions suggest a constrained vulnerability too. I presume Cameron personally believes that he was right to be wary of allowing thousands of refugees into the UK before that photo of a dead child was published. I assume also that he is personally against an EU quota, in which members of the EU accommodate refugees according to their current population levels and other agreed criteria. But fragile, narrow-minded expediency plays a part in his calculations too.

Because the outcome of the general election was a surprise, Cameron and George Osborne are portrayed as giants, titans ruling without obstacles of any significance. In reality they have a majority in the Commons of 12. They are acutely conscious of their parliamentary fragility. Earlier this summer there was no guarantee that most of Cameron’s MPs would have welcomed even the cautious balanced “third way” statement he made yesterday afternoon. Even now there are plenty of intelligent doubters, such as David Davis, putting forward valid arguments about the risks of moving with this latest tide of public and media opinion. With a tiny majority, Cameron needs to move carefully at all times.

Cameron's sense of strength and vulnerability applies also in the approach to military action in Syria. During his statement, he also revealed that an RAF drone attack took place last month on British Isis fighters in Syria. He insisted the attack was legal and an act of self-defence. Still, he felt politically strong enough to authorise the strike when, before the election, Parliament had voted against military action in Syria. With good cause Labour’s acting leader, Harriet Harman, wanted to know more about the evidence to justify the strike. She did not get more details. Immediately after, I spoke to two very senior figures – one Labour and one Conservative – who had voted against military action in Syria. They were uneasy and wanted to find out more about the incident. Cameron will have known he would generate unease but felt strong enough to press ahead.

George Osborne was also candid about the government’s constrained scope for a military option in Syria in his interview with Andrew Marr on Sunday. Osborne argued that, although he and Cameron wanted military action in Syria, they will not come forward with a proposal if they cannot guarantee winning a Commons’ vote. On one level this is a statement of the obvious; Cameron is not going to risk being defeated again. The argument is also partly an attempt to reignite Labour’s divisions over the issue. But it is also a significant public admission of weakness in the face of a tiny Commons majority. They want to act militarily, wrongly in my view, but they do not know whether they will be able to do so.

The fragile parliamentary context seemed to shape Cameron’s broader thinking in relation to the refugee crisis. His statement yesterday was narrow and incremental. There was no sense of historical sweep, no evocation of a challenge for the whole of Europe, that Europe would have to manage together. Presumably he does not personally see the crisis in such terms. But even if he did, he would not be able to act on an EU-wide basis because parts of his party would not let him.

Cameron has a referendum to fight, one in which he and Osborne plan to argue that the EU has changed, with some countries integrating more closely and others like the UK having a looser arrangement. Cameron’s response to the refugee crisis, in which the UK makes unilateral decisions rather than co-operating with the EU, becomes part of his early attempt to win a referendum and keep his party united. Again Cameron is defiant, sticking with his original stance of refusing to co-operate with Merkel’s plans for an EU quota, and yet weak in his focus on party considerations at a moment of historic challenge. Media and public opinion spur a modest shift from Cameron. I doubt if it will be enough to address the scale of the crisis or the change in an admittedly fickle public mood.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments