Cecil Rhodes protest: On Whitehall's 'murder mile', the Empire's heroes are steeped in innocent blood

During the recent campaign to remove Cecil Rhodes' statue from a college in Oxford, its leader claimed the city's very architecture was an affront to 21st-century sensibilities. He should try a stroll round central London's statuary, says Charlie Gilmour. On 'murder mile', the Empire's heroes in marble and bronze are steeped in innocent blood

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Britain, if you're a mass murderer, your fate seems to depend largely on how many people you kill. Slaughter a few innocents and you'll be counting bricks in Belmarsh for the rest of your years; spill the blood of continents and it's Portland stone and a plaque in your honour.

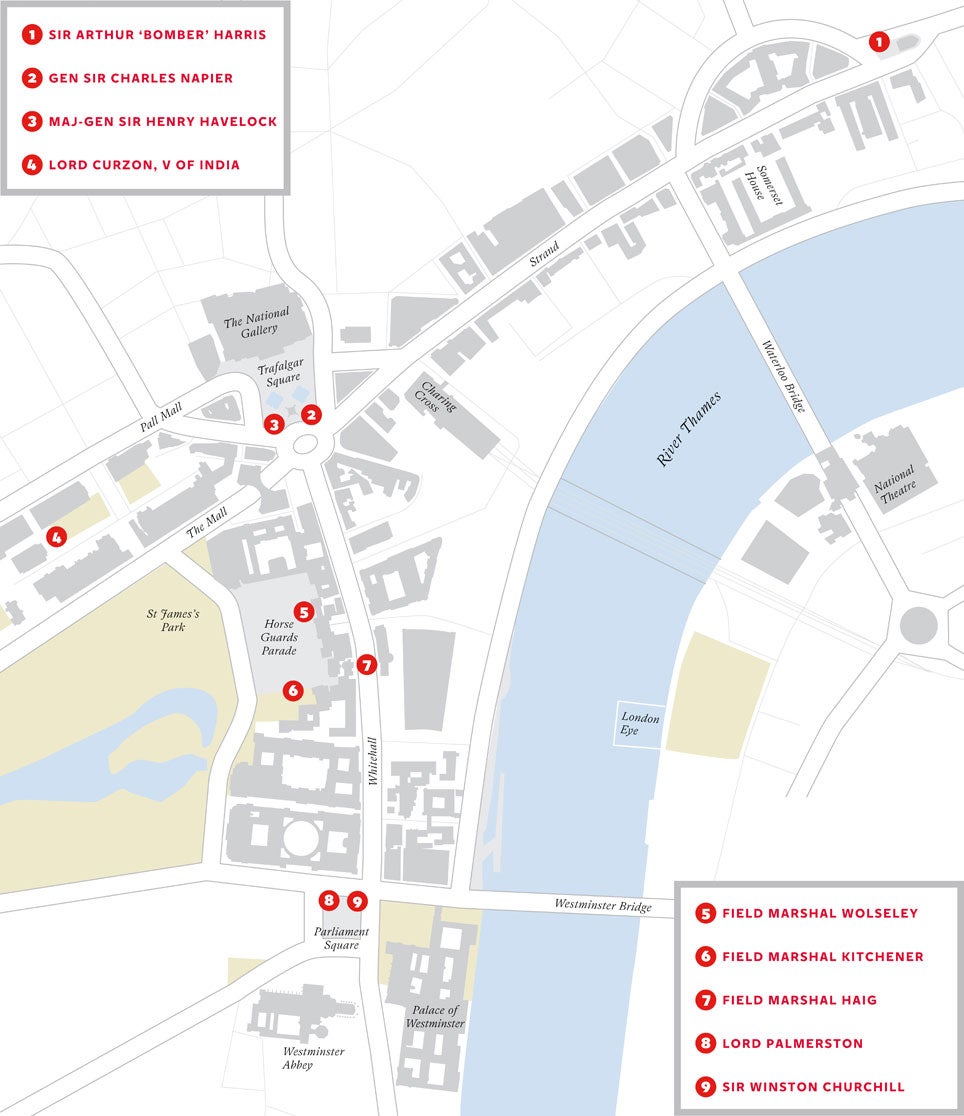

Campaigners in Oxford recently made headlines with their attempts to topple a statue of Cecil Rhodes. Organising member of Rhodes Must Fall (RMF), South African law student Ntokozo Qwabe, even claimed the very architecture of the city was laid out "in a racist and violent way". But can stone and metal really engender such feelings? Well, a brisk walk through central London certainly turns up a killer on every street corner. Forget Clapton or Moss Side: Whitehall's the real "murder mile".

Unlike in Russia, where from 1991 statues of Stalin and other undesirables were dumped unceremoniously in Fallen Monument Park, or Germany, where you'd be hard-pressed to find anything glorifying its most recent empire, Britain has yet exorcise its imperial past.

The short stretch from the Strand to Parliament Square contains more butchers than Smithfield Market. Together, they're either directly responsible for or implicated in the deaths of as many as 30 million people.

When I arrive on the Strand to begin this atrocity tour, the first item on the agenda – a larger-than-life statue of Sir Arthur "Bomber" Harris – is under armed guard. It's nothing personal: Princess Kate is gracing the nearby RAF chapel with her presence. She blithely greets current members of the air force beneath a bronze of the man who, as commander-in-chief of Bomber Command during the Second World War, was, among other things, responsible for the incineration of at least 25,000 civilians at Dresden.

Unlike in 1992, when the Queen Mother unveiled the thing, there are no boos from protesters – dubbed "peace idiots" by the Daily Mail – just exited squeals from tourists who can't quite believe their luck. Nor are there any traces of the splashes of red paint that meant it had to be guarded by police day and night for several months afterwards. The history of dissent has been wiped clean, and the plaque beneath contains no reference to what many consider to be a war crime.

Harris is unusual – but not for his body-count. Rather, he is one of the few statue-people whose victims were mostly white. Passing General Sir Charles Napier, conqueror of much of what is now Pakistan, and Major General Sir Henry Havelock, hammer of the First Indian War of Independence – who still hold their ground at Trafalgar Square, despite an attempt by then-mayor of London Ken Livingstone to get rid of "the two generals that no one has ever heard of" – and walking down Carlton House Terrace, we come to the feet of Lord Curzon.

As Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905, Curzon oversaw one of many famines to afflict the subcontinent during the period of British rule. As about 1.25 million people starved to death, and a further two million perished from disease, Curzon cut rations he considered "dangerously high" and attacked "indiscriminate alms-giving" that "weakened the fibre and demoralised the self-reliance of the population".

Stringent tests were introduced that deprived many of aid. In the Bombay district alone, the government boasted that it had deterred a million people from claiming. The relief camps – in which the starving were forced to engage in strenuous physical labour in exchange for help – were made as unpleasant as possible. Essentials such as blankets and fuel were regularly withheld. The Guardian's horrified correspondent described the situation as "a grand hunt of death with scores of thousands of the refugees at the famine camps for quarry". But today Curzon stands unchallenged, dressed in mock-Roman garb, above a plaque that reads: "In Recognition of a Great Public Life."

Across the Mall, on Horse Guards Parade, Field Marshal Viscount Garnet Wolseley sits proudly astride his mount. Such a fine military leader was he that the phrase "everything's Sir Garnet" became army-speak for "everything's great, thanks!" Engraved in the rear of the pedestal is a list of the campaigns in which he served: Egypt 1882; South Africa 1879; Ashanti 1873-4; Red River 1870; China 1860-1; and, of course, the "Indian Mutiny" of 1857.

Britain's response to what is more correctly referred to as India's First War of Independence was truly savage. A captain at the time, Wolseley recalls having sworn an oath "of having blood for blood, not drop for drop, but barrels and barrels of the filth which flows in these niggers' veins for every drop" of British blood that had been spilled by the rebellious sepoys [Indian soldiers].

While most accounts suggest about 100,000 Indians were killed following the rebellion – in many cases, forced to lick blood from the floor before being hung, bayoneted in the stomach or tied over cannon and blasted to smithereens – historian Amaresh Misra has calculated that almost 10 million were in fact wiped out over the next decade. As one British official recorded after the event: "On account of the undisputed display of British power, necessary during those terrible and wretched days, millions of wretches seemed to have died."

On the other side of the parade is a hero, at last. Field Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum was one of the truly great men of the British Empire – so much so that his image was famously used for recruitment purposes during the First World War: "Your country needs you!" But it wasn't just Britain's youth that he ushered into an early grave. During the Second Boer War, in response to the guerrilla tactics of the Afrikaners, he vastly expanded the use of a new tactic: the concentration camp.

Tens of thousands were interred in filthy, under-supplied and exposed camps. Emily Hobhouse, a campaigner who made it her mission to expose conditions, wrote that "the whole talk [in the camps] was of death – who died yesterday, who lay dying today and who would be dead tomorrow". The reward for her efforts was an attack piece in the Daily Mail, written by that great author of Empire, Edgar Wallace (Sanders of the River, King Kong and scores more). It was headlined, simply, "Woman – The Enemy".

By the end of the war, 28,000 Boers, mostly women and children, had perished in the camps. The black victims of the policy went uncounted. Years later, when the British Ambassador to Germany expressed concerns about Nazi use of concentration camps, Hermann Goering reached for his encyclopaedia: "First used by the British in South Africa," he announced. It's hard to imagine a more inappropriate figure for us to place on a pedestal – yet there he stands.

Down Whitehall, giving a wide berth to General Haig, the bloody-minded butcher of the Somme, we arrive at Parliament Square, where statues dot the green like giant chess pieces. To the north, there's Lord Palmerston, declarer of the First Opium War and poster boy for "gunboat diplomacy", whose time at the Foreign Office was described by the Liberal politician John Bright as "one long crime"; next, Jan Smuts, a South African statesman whose advocacy of racial segregation laid the ground for apartheid; and finally, Sir Winston Churchill himself.

True, Winston beat the Nazis. But a game of "Who said it: Hitler or Churchill?" is still more difficult than one might think. Who called for the "feeble-minded" to be "segregated under proper conditions so that their curse died with them"; suggested "mental defectives...tramps and wastrels" be sent into forced labour; and warned that the "multiplication of the unfit" constituted "a very terrible danger to the race"? I'll give you a clue: not Hitler.

Unfair? One of his own cabinet ministers, Leo Amery, accused him of having a "Hitler-like" attitude when it came to India. And remember – the war effort bled India white. During the first half of 1943, even as famine set in, 70,000 tonnes of grain were extracted for use abroad. Churchill was reportedly unmoved. "The starvation of anyway underfed Bengalis is less serious than [that of] sturdy Greeks," he said. But then, he didn't have time for most Indians. Hindus were, he later said, "a foul race" who, in any case, "breed like rabbits".

The consequences were devastating. As Pier Brendon writes in The Decline and Fall of the British Empire: "Clutching infants of skin and bone, skeletal women cried for alms... Every morning corpses, decomposing in the steamy heat and often gnawed at by rats or jackals, littered the streets." As many as three million perished in what some refer to as the "Bengali Holocaust". Which sure puts Cecil's achievements into some perspective. Of course Rhodes Must Fall, but so too must Churchill, Kitchener, Wolseley, Curzon and the rest; in fact, statues that deserve their pedestals seem to be few and far between. So, what to do?

As the Oxford campaigners have been discovering, resistance to change is, well, set in stone. Lord Patten, Chancellor of the University, responded to the demands of the Rhodes Must Fall campaign by suggesting that its supporters should "think about being educated elsewhere". Many online responses were just as bad. "Cecil Rhodes did more for Africa then you'll ever do," wrote one typical commenter.Then, after RMF won an Oxford Union debate, donors stepped in and threatened to withhold funding. And so – for the present, at least, – Rhodes Must Stand.

For insensitivity, perhaps? As Dalia Gebrial, an organising member of RMF says: "I wasn't quite aware of the level of cognitive dissonance that exists. People really don't know what the realities of the British Empire were. It's not that surprising – I studied history to A-level standard and I never once engaged with the Empire. But Rhodes is not an exception. His statue exists within a wider trend: the nationalistic distortion of history," says Gebrial. "This notion that we shouldn't interrogate one statue because it might compel us to think more broadly about other statues and history is absurd."

Still, Britain's nostalgic view of Empire seems to be very much entrenched. A recent YouGov poll revealed that more than 40 per cent of people believe that British colonialism was "a good thing" and remains "something to be proud of". Which might explain why – when some Royal Holloway University students recently posted a group-photo of themselves next to an on-campus statue of the "Empress of India", with the question "How can we feel included when there's a statue that celebrates the subordination of our people?" – they started an online storm. .

"I had some seriously nasty comments," says Grace Almond, vice-president of the Royal Holloway Women of Colour Feminism Society. "People trying to defend Queen Victoria, saying that colonialism was the best thing to happen to India." She finds the sheer hypocrisy of her attackers almost overwhelming. "People don't seem to have a problem with the fact that British people were looting India and Nigeria and all sorts of other colonised countries and bringing it back over here. But, as soon as you suggest knocking down a statue of someone who is – in my opinion – one of the most evil men to ever walk the planet, people get extremely defensive."

One soft option is to simply update the monuments. In 2004, Italian artist Eleonora Aguiari famously covered the equestrian statue of another imperial figure – Lord Napier of Magdala, who sits at the gates to Kensington Gardens – entirely in red tape. "We have to discern between what's good about our past and what is not – or no longer – good," she says. "I believe in transformation more than destruction. It would be interesting to use these statues as a base for a new message, to transform them into something more in line with the new moment and society."

From a different perspective, Professor Mary Beard, the TV historian, author and Cambridge don, has consistently opposed the toppling of Rhodes. "Wanting to preserve his statue is not about saying that Rhodes was a good guy," she claims. " But I think people have to see...what we're the beneficiaries of. I want to empower [students] to put two fingers up to that statue and say: 'He was wrong.' We've got to be able to look these figures from the past in the eye; otherwise we just push them underground, and that doesn't solve the problem."

From across the quads, though, comes a dissenting voice. Actually, says Dr Priyamvada Gopal of Churchill College, Cambridge, tearing down statues is an "interesting idea". She continues: "I would welcome any move that actually began the process of undoing imperial amnesia, a condition that afflicts large swathes of Britain, not least élite institutions." Britain, she adds, needs to "look at itself in the mirror and finally undertake a reckoning with a history that is not beautified or sanitised",

For her, RMF was, and is, far more than a reductive debate about masonry. "As the campaign has demanded," says Dr Gopal, "at a practical level, there needs to be a totally honest accounting-for of Britain's imperial past, combined with a monumental effort to acknowledge how the legacy of that past shapes the present – including in relation to immigration, racism and the BME [Black and Ethnic Minority] presence in British institutions such as Oxbridge – and a decolonising of the curriculum in the arts and humanities to make it not just more 'inclusive' but considerably less centred on white Britons."

She can take heart. While the statues might not be torn down in the foreseeable future, the structures that support them are slowly but surely being eroded away. RMF started in South Africa, spread to Oxford, and now, across the nation, the legacies of Britain's colonial past are being interrogated on campuses and in society at large. Meanwhile, from new and popular cultural hubs such as the Decolonising Our Minds Society, formed by London students to "critically examine the legacy of colonialism" through debates, poetry nights and hip-hop events, to Facebook groups such as Why Is My Curriculum White?, there is a sense that a "reckoning with history", as one activist calls it, is at hand.

There's an African proverb that Grace Almond always bears in mind: "Until the lions have their own historians, tales of the hunt will always glorify the hunter." And she's a lion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments