Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hearing of last week's "night of the long knives" Cabinet reshuffle, in which the Prime Minister sought to promote a group of ambitious younger women at the expense of a band of fifty-something men, and reading the numerous articles that followed in its wake by middle-aged males lamenting the fact that their professional lives seemed effectively to be over, I found myself thinking of two Conservative politicians, each of whose careers has some bearing on the eternal generational conflict between youth and seniority.

The first is William Hague, in whose college rooms I once lurked about a third of a century ago helping to lay out some student manifesto or other. This, I thought to myself, eyeing up a domicile whose ornaments included a signed photograph of Margaret Thatcher and a book entitled The Pursuit of Power, while the officers of the Oxford University Conservative Association swarmed sedulously around us, is a man who clearly intends to devote his life to politics. But no, here we are a mere three and a bit decades later and Mr Hague, having failed to acquire the supreme prize to which his ambitions inclined him, is detaching himself from the political process at the ripe age of 53.

The second is Leo Amery, Secretary of State for the Colonies between 1924 and 1929 and Secretary for India in Churchill's war cabinet, who, after a 34-year tenure, lost his seat of Birmingham South in the Labour landslide of 1945. Undeterred by this rebuff, and at this point in sight of his 72nd birthday, Amery immediately began to explore the possibility of finding a new constituency. According to his biographers he was baffled to discover that, here in the wake of a parliamentary melt-down, the party was, in that ominous phrase, "looking for younger men".

All that was nearly 70 years ago, at which point the battle for precedence between young and old had only just got going. Here in 2014 it has not only been decisively won by the youngsters, but extended its scope to practically every branch of politics, industry, commerce and the arts. I can always remember the horror with which I greeted the news, a year or two back, that the judges of some literary prize had decided – another ominous phrase – to "skip a generation" by excluding Ian McEwan and Martin Amis from their shortlist: not merely because these gentlemen were the enfants terribles of my own adolescence, but because literary prizes are supposed to reward merit and there is no hard-and-fast law of creativity that says it vanishes with age.

Anyway, youth won; the accountants' offices in London Wall are full of 30-year-old audit partners; last year's Man Booker prize was won by a 28-year-old, and an undergraduate contemporary of mine was recently appointed head of an Oxford college – a job previously reserved for retired civil servants – at the age of 51. The fascination of this momentous demographic shift lies not only in its implications – more of these in a moment – but in the sheer speed of its historical advance.

Throughout the 19th century, for example, the idea of "young people" as a social category barely existed. Thackeray's novels are full of the embarrassments suffered by teenage boys once family dinner parties had broken up: not wanted by the men, who feared the consequences for their manly chats over the port, and a hindrance to the ladies, who wanted to trade scandal above the teacups.

Naturally, the First World War offered a crucial stepping stone to the emergence of "youth". Not only did the slaughter of so many young men on the Western Front between 1914 and 1918 make it a desirable quality in itself, but there was also a widespread feeling that responsibility for the Flanders campaigns could largely be laid at the door of the social entity known as "old men in clubs". The teenager might not yet have existed, but many a novel was predicated on the failsafe newspaper discussion topic of the "younger generation" and lucrative Fleet Street careers could be fashioned by writers – most notably Evelyn Waugh – who set themselves up as generational spokespersons. "England has Youth. Make Use of It" was one of Waugh's early efforts in this line.

And yet a glance at the political and cultural arrangements of the 1940s and early 1950s reveals just how incremental this advance turned out to be. The general election of 1951 was won by a man of 77 against an opponent of 68, who went on to lead his party for another four years. The best-selling paperback author of 1946 was the 90-year-old George Bernard Shaw, 10 of whose plays were issued simultaneously in Penguin. A S Byatt (born 1936) has recalled how the role models offered up to teenage girls in the post-war era were almost exclusively maternal: the married woman with her swarming brood and her dutiful husband was still regarded as a much more potent lure than the flat-sharing, latchkey-toting bachelor girl about town.

Looking about for the most significant force lined up against age, wisdom and seniority in the post-war world, one finds it, infallibly, in the media. As the tidal wave of American mass consumer culture broke upon these shores in the mid-1950s, no one was more youth-conscious than the average newspaper editor. Hugh Gaitskell, still in his forties when elected Labour leader, and with a glamorous wife to boot, seemed a creature from another planet when set against the 80-year-old retired miners of the Opposition back bench. Back in the world of the arts, several papers began an unseemly competition to find the youngest literary prodigy – a title eventually scooped by a nine-year-old French girl named Minou Drouet who was persuaded to write a poem live on Panorama.

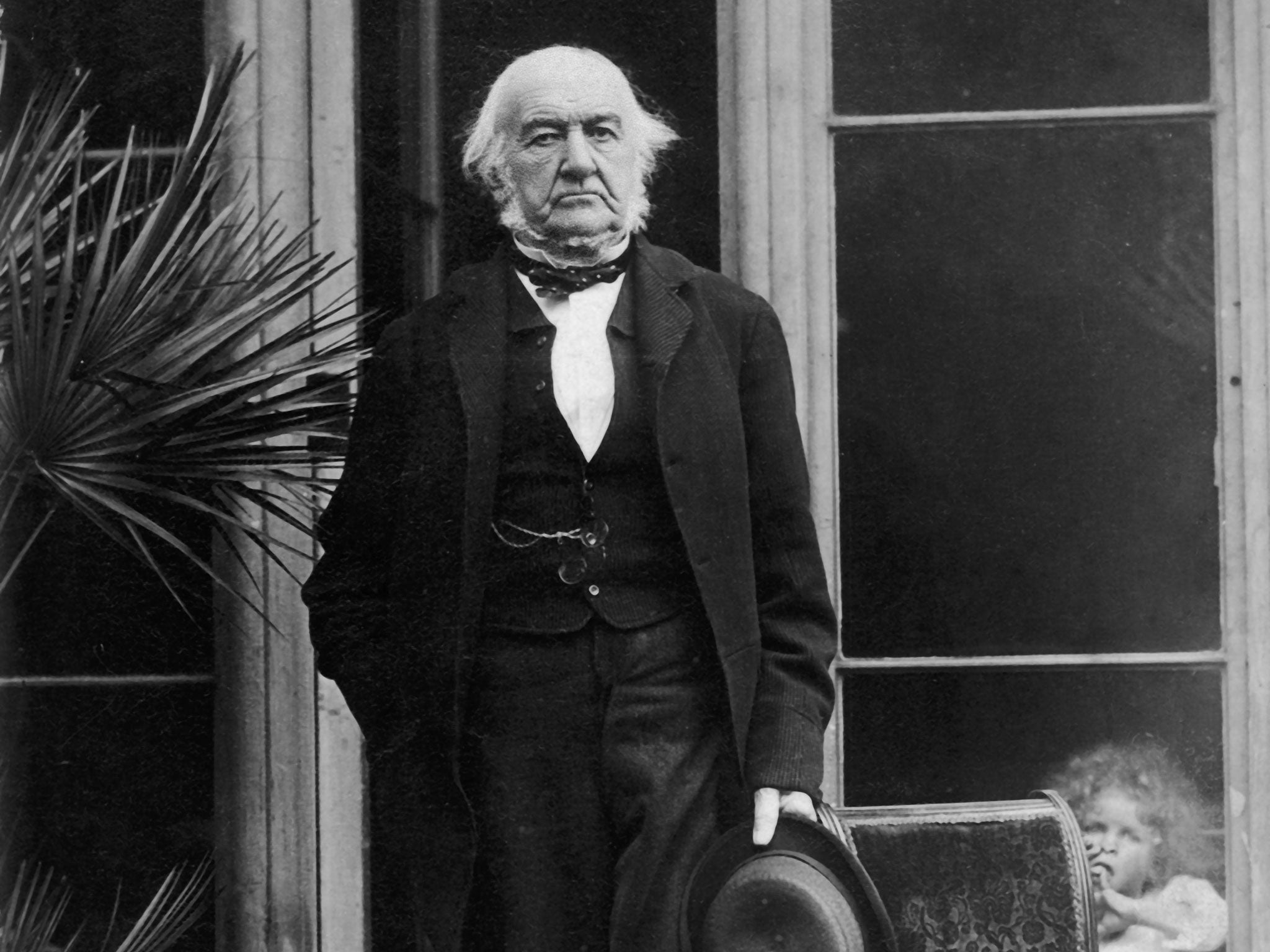

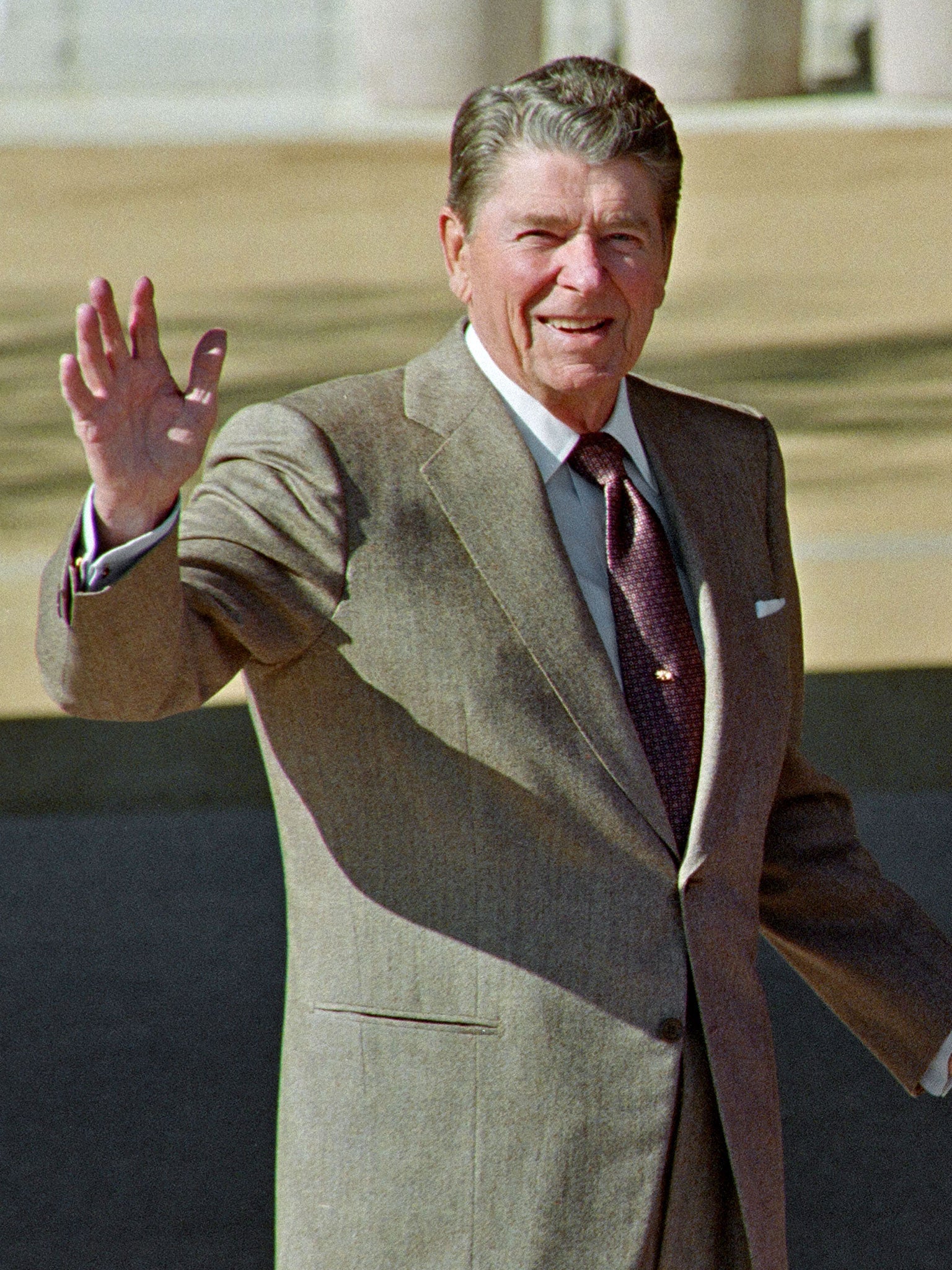

Sixty years later, with the leaders of the main political parties all under 50, and the soon to retire President of the United States a stripling of 52 – compared, that is, to Ronald Reagan, who went on until 77 – many of the implications of this obsession with youth have yet to be grasped. William Hague, it seems generally accepted, has been quite a good Foreign Secretary: why should he be abandoning parliament at an age when Gladstone was merely getting into his stride? Several of the new Cabinet ministers, as commentators have pointed out, have no experience of the departments they are now commanding. They are simply there to provide window dressing for a Prime Minister anxious to show he is in touch with whatever demographic currents can be perceived beyond the Downing Street window.

But there is a wider difficulty beginning to rear its head, over and beyond the limited and specialised world of politics. The world – the Western world at any rate – is growing older, and yet its advertising, its consumer durables and its technology are still aimed at the young, a part of the populace with no money and little influence. In all kinds of ways the interests of an ever-growing number of old people are being administered by an ever diminishing number of young people. One might not go so far as Martin Amis, who some years ago predicted a generational war between resentful pensioners and ingrate under-30s, but one doesn't need to be a 21st-century Alvin Toffler to predict that, sooner or later, there will trouble about this.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments