Behind good news headlines on recovery and jobs we are no better off than at the start of this slump

Recession will have lasted three years longer than any other in the past 100 years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Look behind the headlines and the “good news” for the UK from the International Monetary Fund and the jobs market wasn’t actually too much to celebrate. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook raised its forecast for the UK by more than for any other country, by 0.6 per cent in 2014 to 2.4 per cent and up 0.2 per cent to 2.2 per cent in 2015. But this is slow growth that likely will not be enough to lift living standards much at all. Even if the economy does grow by the amount predicted, by the time of the election in 2015 it will have barely restored the output level at the start of the recession.

The recession will have lasted three years longer than any other in the past 100 years. And don’t forget the IMF forecasts are still markedly lower than those for the United States of 2.8 per cent and 3.0 per cent which, in output terms, continues to strongly outperform the UK. By the start of 2015 if the IMF’s forecasts come to fruition, US output will be over 8 per cent higher than at the start of the recession compared with the UK’s big fat zero.

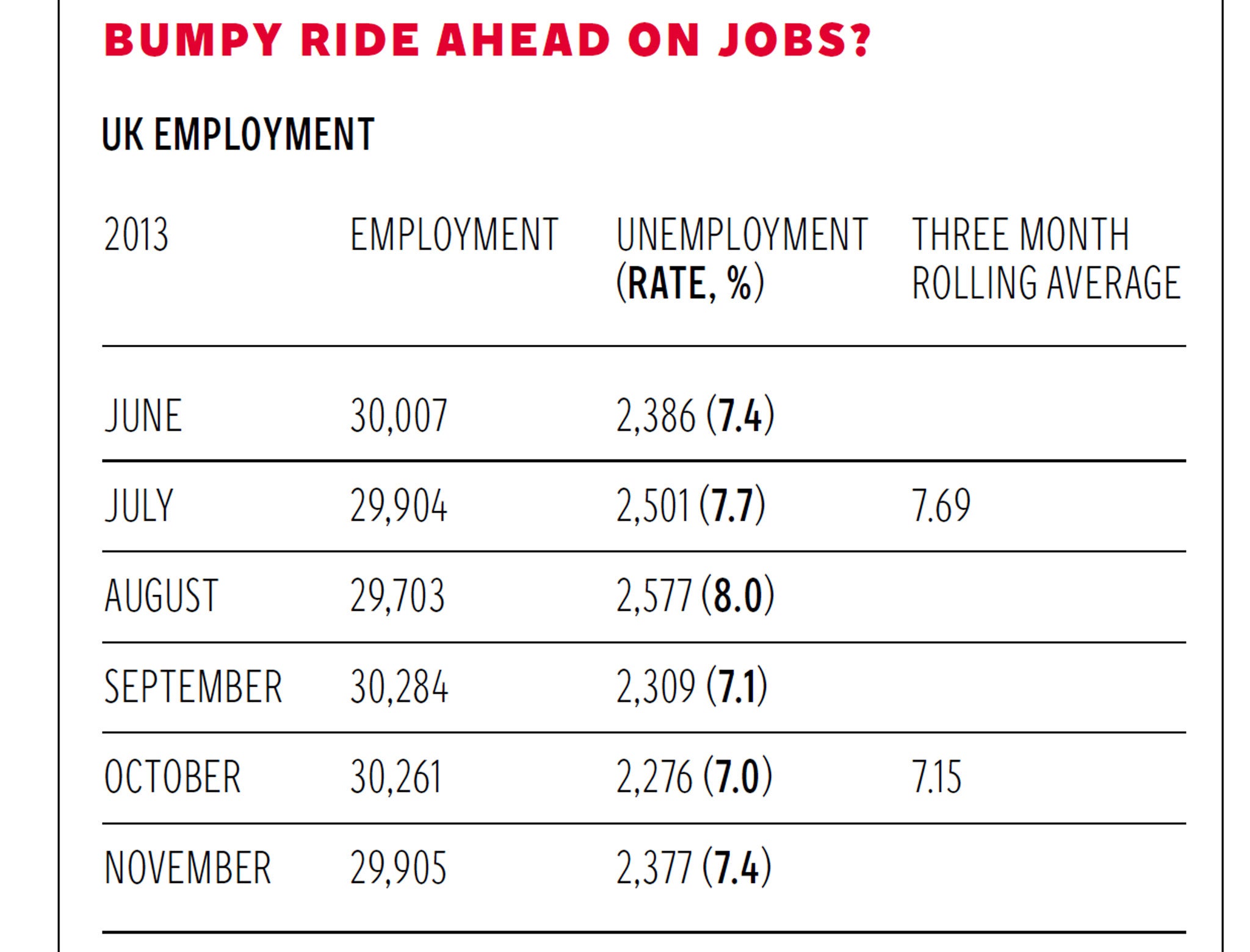

But then there were those good jobs numbers. Again, the big story remains that real wages continue to fall; average weekly earnings growth remained unchanged at 0.9 per cent, so real wage growth continues to fall at over 1 per cent a year. Improvements in the three-month rolling average of employment and unemployment though grabbed the headlines.

Compared with June to August, the data for September to November suggested that employment rose by 280,000 while unemployment fell by 167,000, with the unemployment rate dropping to 7.1 per cent. The numbers of part-time workers who wanted full-time jobs and the numbers in temporary jobs wanting permanent jobs also fell, but the number of inactives who couldn’t find a job rose a little, by 10,000.

But as the table shows, the single monthly data used to create the rolling averages painted a less rosy picture – and puts in question where we go from here. The three-month rolling average of employment in June-August of 29,871,000 compared with 30,051,000 for July-September shows a rise in employment of 280,000, despite the fact that on the month, employment fell by 357,000. Similarly, despite a big fall in the quarterly unemployment rate, the latest monthly estimate jumped from 7.0 per cent to 7.4 per cent; in contrast unemployment on the month rose by 100,000. I should caution of course that these monthly numbers are highly volatile; the big question remains whether the September and October numbers were just pleasant outliers and a harsher reality is now about to return, or perhaps we are just headed on a delightful but bumpy downward trend.

The sharp fall in the unemployment rate to 7.15 per cent from 7.69 per cent means that the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee is faced with the prospect that one of its triggers for raising interest rates may soon be breached, even though for once, inflation is at target. In an important speech rate-setter Paul Fisher argued that, “even if the 7 per cent unemployment rate threshold were to be reached in the near future, I see no immediate need for a tightening of policy”. He noted the MPC is a long way from tightening because of the levels of output and employment, not their growth rates. After nearly six years since the start of the crisis, the level of output in the economy is still 2 per cent below its peak in 2008. “A conservative extrapolation of the pre-crisis trend would suggest that UK output is some 15-20 per cent below where it would have been expected to be by this time in the absence of the crisis.” That seems right.

A rate rise would not be good for the Tories’ electoral prospects despite George Osborne’s suggestion this week that he had no problem with it. This is trying to have it both ways given that he warned in 2011 that a 1 per cent rise in lending rates “would add £10bn to household mortgage interest repayments and £7bn to business costs”. Interestingly, despite better economic news, the Tories have seen no improvement in their poll ratings, presumably because living standards are still falling for most people.

I should add as an aside note that the fall in the unemployment rate remains a major puzzle. No forecasters and economists, including me, had expected to see so much of the strain being taken by wages. There was nothing in the data pre-recession to make anyone think that wages in the UK were more flexible than those in the US. I suspect a good deal of the reason is because variable rate mortgages in the UK resulted in reductions in mortgage payments which meant wages were more flexible. The drop in mortgage payments cushioned the shock. A public sector pay freeze in the UK wasn’t repeated in the US, plus fixed interest rate housing loans in the US meant mortgage payments didn’t fall over the cycle.

The concern is that in the recovery phase the UK is highly interest rate sensitive. Wages are unlikely to rise much until the unemployment rate approaches full employment which in my view is likely to be below 5 per cent and we are a long way from that. Unless real wages rise hugely over the next 18 months the Labour Party will be able to ask the question on election day in May 2015, “are you better off under the coalition than you were in May 2010?” The answer will almost inevitably be “no”. Sorry George.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments