As the daughter of a billionaire, I know it is right not to leave millions to your children

Great wealth is not beneficial to someone who has not earned it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

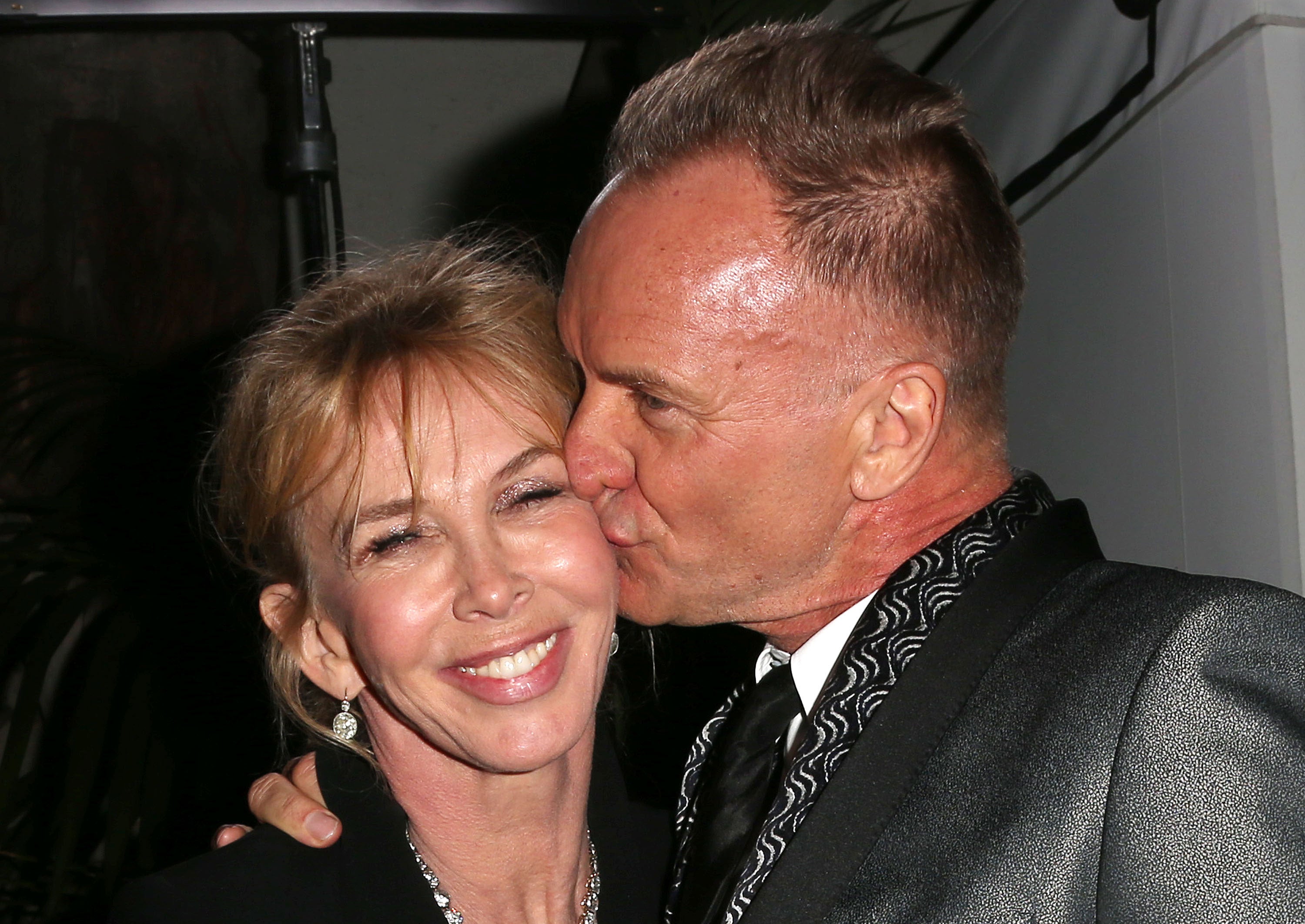

Your support makes all the difference.Got rich parents? Then you’ll be rich too, right? Well, actually, no. Take Sting’s offspring, for example. The Police frontman and tantric sex god – a giant of pop’n’rock for 35 years and a man worth £180 million – just revealed that his six children – ages ranging from 37 to 18 – can’t expect a great big inheritance.

In an interview with this week’s Mail on Sunday Sting said: “I certainly don’t want to leave them trust funds that are albatrosses round their necks.”

Is inheritance such a burden to bear? A signal to others to stay away, for here lies evil? A person made lazy, greedy, materialistic by unearned wealth? We do tend to approach rich kids with a vague distaste and suspicion. We don’t feel warmly predisposed to people who have such an unwarranted head start in life. Even I scoff at rich kids, and I am one of them.

My father, the philanthropist and mobile phones entrepreneur John Caudwell, has done his best to navigate what is essentially unknown territory to him: money and offspring. Never before has a Caudwell had to worry about the consequences of an excess of money.

One thing he always felt was that nothing noteworthy was ever born out of complacency. You have to be hungry; you have to have fire in your belly, courage in your heart and rage, rage against your circumstances. You take away the survival instinct and what are you left with? Dad battled his way out of poverty, lean and hardened while all I do is bat away the malaise that comes with a safe, soft life. It’s never really that simple, and I’m not unburdened by strife, but I know my fight does not begin to compare with my father’s. Who knows if I am the better or worse for it?

Dad sensed early on that great wealth is not psychologically beneficial to someone who had not earned it. He made it clear early that he was not amassing wealth for his children to fritter but in order to gather the resources and power to redress some of the great injustices of the world. As a member of Bill Gates’s Giving Pledge, he has already committed to giving away at least half of his wealth to philanthropic causes upon his death. And the rest he wants his family to disperse via the Caudwell Foundation.

In the meantime, I’ve reached my mid-20s unaided – or burdened – by huge paternal hand-outs. Privileged, certainly, but not excessively so, I believe. For now, I have a job

and live off what it pays me, and am no different from my friends and colleagues. Will my siblings and I eventually receive anything personally? I’d like to think that I’ll get a contribution to my handbag fund but the fact is that we just don’t know. We can’t bank on anything. And thank God: I suspect the flickering candle of my own ambition would be extinguished entirely by such a promise.

Money does not have to be the albatross borne by the future generations. It does not have to be a signifier of incompetence, indolence and apathy. We have shining examples in Holly and Sam Branson – Richard’s children - who seem to have pulled the albatross from about the necks and have restored it to the sky: an omen of good fortune once more. Wealth springs myriad opportunities and can inspire greatness in those who have the strength of character.

For the rest of us: being good is enough. Over the years I battled with feelings of inadequacy, uselessness and the paralysing fear of not living up to the opportunities afforded me. Dad would reassure me that his expectations were pretty humble: “To be good, happy members of society who contribute more than they take away. That’s what I hope for my children.”

Isn’t that what we should all strive for? And money can either be a massive help or a massive hindrance to that. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the parent to know if and when their child is able to utilise money to that end. One thing’s for sure, though: no one ever squandered, snorted and partied their way to happiness.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments