Adolf Hitler's ‘Mein Kampf’ is the story of more than one struggle

Churchill thought the book demanded vigilant attention. He is still correct

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few visitors to the National Gallery’s recent show of Viennese portraits from around 1900, “Facing the Modern”, will have lingered long over an insipid family group by Alois Delug. The artist was, in every sense, an academic painter. He taught at the city’s school of fine arts in the years before the First World War. According to a later account, Delug while wearing his professorial hat one day turned down a keen would-be student. He had good reason. The no-hoper applicant couldn’t manage more than pitifully conventional, cack-handed daubs.

Looking on the bright side, the reject later claimed the prof had said: “My talents obviously lay in the field of architecture.” Yet at the time he was “downcast”, and bitterly disappointed. “I was so convinced of my success that the announcement of my failure came like a bolt from the blue.” The candidate felt “dissatisfied with myself for the first time in my life”.

Would 20th-century history have taken a turn for the better had Delug (if it was indeed him) softened and offered a place to the young Adolf Hitler? A double rebuff from the Vienna academy deepened the alienation experienced by a penniless loner of small talent and few prospects. Like so many country kids adrift in the big, scary and impersonal city, this one looked around for a pattern, a story, that would make sense of his solitude and give meaning to his plight.

Descending step by step into the anti-Semitic abyss, Hitler found an enemy to give purpose to his life: the Jews, with their socialist politics and degenerate art that “denies the value of the individual in man, disputes the meaning of nationality and race”, thus “depriving mankind of the assumption for its existence and culture”. The vague anti-establishment resentment of this disaffected youngster craved a focus. It soon found one, in the perennially handy scapegoat of the West and – more recently – the Middle East as well. The scorned nobody from Linz, thwarted in the single skill he thought that he commanded, had found a lifelong mission: “By warding off the Jews I am fighting for the Lord’s work.”

I would not exactly recommend that you read the first parts of Mein Kampf. Yet, as forensic evidence of the psychological roots of venomous racism in urban anomie, it is in its own sick way a precious document. Anti-extremist activists could still study it with profit. On the eve of Holocaust Memorial Day, as witless footballers and mirthless “comedians” fling their arms across their chests in a knowing bad-boy gesture that can strike only one target, we may need more than ever to illuminate the path that leads from humiliation to hate. But in which format, and under whose eyes?

The edition I quoted came out in the US in 1939. It was co-translated by a team of anti-fascist scholars from the New School of Social Research in New York. Even then, more than two years before the US entered the Second World War, they sought to draw a moral and intellectual cordon sanitaire around the besmirching volume. “Mein Kampf is a propagandistic essay by a violent partisan,” their preface squarely states. “We have therefore felt it our duty to accompany the text with factual information which constitutes an extensive critique of the original.” Which they, admirably, do.

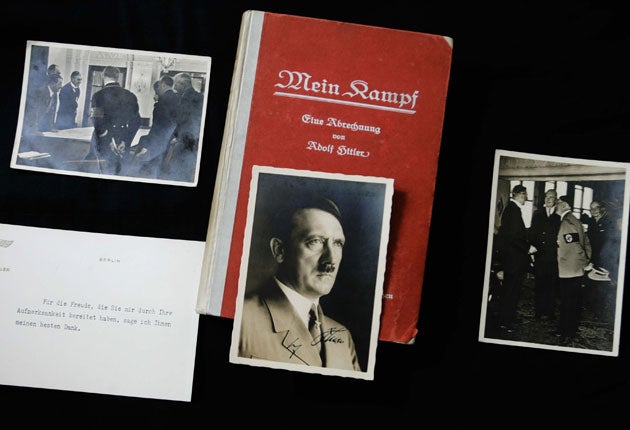

Three-quarters of a century later, the same anxieties surround the same incendiary testament. This week, the Bavarian state government in Germany flip-flopped yet again. After an agreement in 2012, then a reversal last year, it will now authorise an annotated critical edition of Mein Kampf to appear in 2016. At that point, in the year that follows the 70th anniversary of its author’s death, copyright will expire and Hitler’s memoirs will enter the public domain.

A tangled and bizarre publication history surrounds Mein Kampf. Pedantic points of intellectual-property law cling to the “literary” legacy of Europe’s most shameless law-breaker. Hitler wrote – or rather dictated to Rudolf Hess – the gargantuan rant in a comfy jail at Landsberg am Lech during his slap-on-the-wrist eight-month imprisonment after the 1923 Munich beer hall putsch.

Forcibly pressed on every German couple as a wedding “present” by the Third Reich, it ran through perhaps 12 million copies. The book earned its author an estimated $150m in today’s values. On the Führer’s suicide in 1945, copyright was held by the Nazi publishing house Eher Verlag. By default, at its liquidation, the state of Bavaria inherited rights to this work by a resident of Munich.

Mein Kampf was never “banned” outright in Germany, although post-war law forbade fresh versions. Meanwhile, US and UK translations continued to rack up royalties that embarrassed their publishers. In Britain, several Jewish charities refused to accept a penny of this loot. The German Welfare Council, originally a refugee support group, handed back the proceeds channelled to it from a UK edition published in 1969.

With the rise of neo-Nazi revisionism, and access to Hitler’s ideas via the internet, scholars of the Institute of Contemporary History at Munich University embarked in 2010 on a project that would – like the work of their New York forerunners – aim to detoxify and defuse those deadly words. The Bavarian finance minister Markus Söder said in 2012 that “we have to demystify this book” by putting it under a scholarly spotlight. Remonstrations from Holocaust survivors led to a U-turn in 2013, now itself overturned. Stefan Kramer, general-secretary of Germany’s Central Council of Jews, backs the critical edition. However, the institute’s version will remain the only legal German print edition.

On the web, of course, it’s open house for the Führer. You can buy his elephantine apologia online for 99 cents. In the US, it has topped the Amazon chart for “propaganda and political psychology”. This week, Amazon.co.uk offered 147 mainly positive reviews with an average four-star rating. “Surprisingly well-written by a surprisingly clever man,” opines one sadly representative punter.

Should we despair, or censor? Neither. Cyberspace and the subcultures it nourishes will mock any attempt to block Hitler’s testimony – or to shackle Dieudonné, for that matter. Churchill thought Mein Kampf demanded vigilant attention. He is still correct, both for the fountainheads of anti-Semitism and every later gush from the same source. The challenge – as with so much noxious material a mouse-click will reveal – has to do with context and conversation. For excellent reasons, anti-racist teaching – of the sort provided by the indispensable Holocaust Educational Trust – concentrates on the grisly outcomes of ethnic hatred. Perhaps, as a prophylactic, we should look not just at how it ends but how it starts.

Read the early stages of Mein Kampf and you see how a “downcast” young man can construct a mental prison for himself. At that point, in 1924 and with his fledgling National Socialist movement in disarray, the bumbling demagogue retains, if not self-knowledge, then enough recall to tell a just-about plausible story. Young Adolf certainly has his problems: menial jobs, grotty lodgings, mocking workmates, heartless officialdom and – topically – a liberal “establishment” culture that makes him feel small and stupid.

From this real distress he builds a fantasy solution in which all the confusion of city life resolves into a single, demonised foe. “In the face of that revelation the scales fell from my eyes. My long inner struggle was at an end.” The peace of the paranoid comforts him. “Thus I finally discovered who were the evil spirits leading our people astray … From being a soft-hearted cosmopolitan I became an out-and-out anti-Semite.”

Pre-genocidal, pre-dictatorial, the youthful Hitler is a thoroughly ordinary bigot. His very banality lets the prepared reader spot each false premise, logical stumble and dive into magical thinking that drags him into the phoney consolations of racism. In the right context of talking and teaching, this descent into abjection could turn out to be the most salutary of warnings. Should his work be proscribed? Perhaps – given alert teachers and a fierce commitment to rebut every subterranean myth that turns kids towards “quenelle” salutes – it should rather be prescribed.

John Milton, in his great 1644 free-speech manifesto Areopagitica, argues that toxic writings can deliver more benefits than healthy ones. Erroneous literature may lead “to a … judicious reader serve in many respects to discover, to confute, to forewarn, and to illustrate”. In the tract’s most famous words, “I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary but slinks out of the race … that which purifies us is trial, and trial is by what is contrary.” Bad books, in Milton’s eyes, may bring about good ends. Even, conceivably, the worst book of all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments