A year older, and I still can’t believe that I’m not the youth I used to be

Reflecting on the early death of his own close relatives, our columnist knows he is lucky to have lived to the age he is. And yet he finds that age hard to accept

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As I write this article, I am a year older than when I last sat down at my desk – the day before. That’s the trouble with birthdays: at a certain stage in life, they remind us with a jolt of the passing of time, like one of those old-fashioned clocks whose hands move in notches rather than a smooth and unintrusive sweep.

The only traditional clock in our home is my mother’s old one, which never quite worked in her day and which long ago defeated all repairers’ attempts at resuscitation. It stands fixed at seven minutes past eleven. I find this reassuring: not on the point of schoolboyish logic that (unlike the clock that gains or loses) it is at least right twice a day, but because time really does seem to stand still in the room in which it sits.

As a schoolboy, I regarded as eccentric the family friend who used wads of sticky tape to obscure all the digital displays of time on various domestic devices in his home, such as ovens and stereos. But now that I am roughly the same age as he was then, the feelings which impelled him to obliterate these digital facia do not seem so very odd. The moment of personal extinction may still be many years away, but it becomes increasingly imaginable: it is not just an embarrassing lack of puff in the lungs, but an unwillingness to see the years graphically displayed that makes me hope there will not be the full complement of candles on the birthday cake.

Resistance

So a sense of timelessness, however much of an illusion that is, becomes ever more attractive. Most of us find a way of attempting this, with meditation perhaps the most deliberate. In a world where everything seems gauged towards immediacy, such resistance is almost psychologically essential.

In his 2009 book, The Tyranny of Email, John Freeman explored the consequences of personal lives permanently hooked up to the sleepless thrum of the world-wide web and diagnosed some sort of sickness, which he termed digital jet-lag, caused by the disjunction of one’s own inner clock from the accumulated speed of billions of internet actions and reactions. As he noted: “The friction between our private sense of time and the objectively observable notion of Time is... the source of our greatest pain and dislocation.”

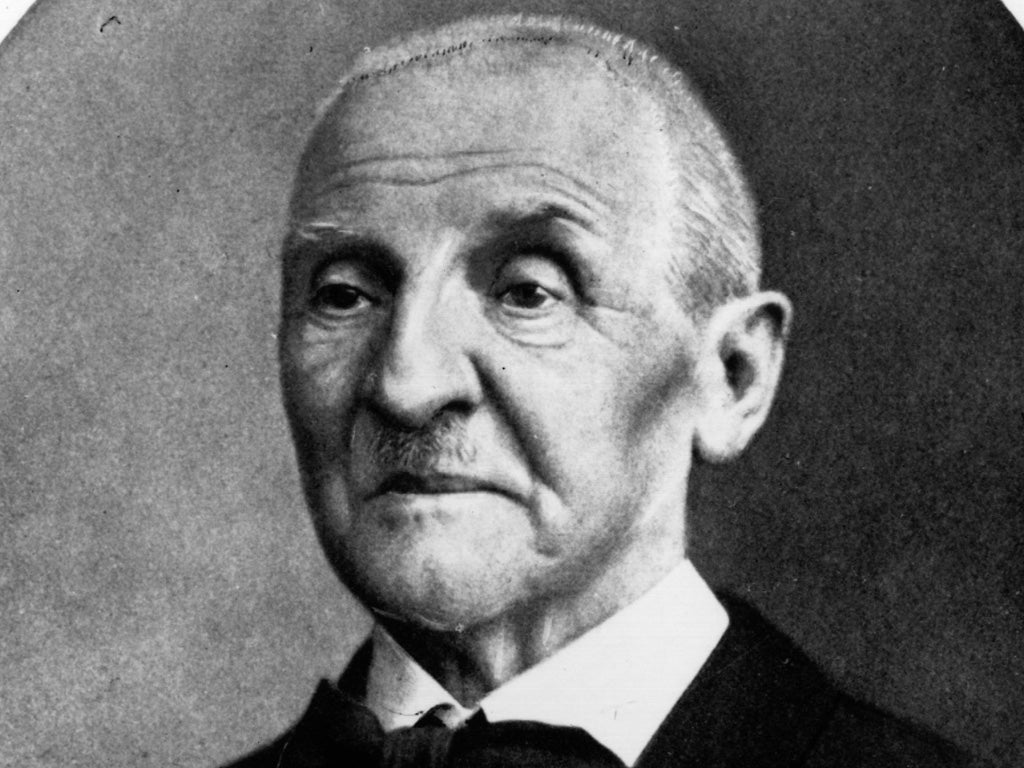

Perhaps this is why music – of the right sort – has such power to restore our inner sense of harmony with time. Its rhythms seem much more natural than the arbitrary events of the world in permanent flux. The greatest composers have been able to create a sense of timeless rapture – and this doesn’t necessarily involve large tracts of time in the purely objective sense, as Mozart demonstrated. On the other hand, I confess a weakness for the music of Anton Bruckner (pictured above), in part because the sheer length of his symphonies prolongs the time we as listeners are lost in his world of almost mystical reveries.

Some serious musicians hate this sense of timelessness: that excellent critic Jessica Duchen wrote in The Independent earlier this year that despite all the well-meaning attempts of colleagues to convert her, she remained “pathologically allergic... Bruckner’s symphonies are stiflingly, crushingly, oppressive. Once you’re in one, you can’t get out again. Spend too long in their grip and you lose the will to live. They are cold-blooded and exceedingly long and they go round and round in circles.”

Yes, they do go round and round in circles, so that the listener does indeed lose track of time – rather like walking in one of those dense Austrian forests that the composer knew so well; but that is exactly the attraction. Duchen went on to observe that Bruckner – whom she described as “the Lumbering Loony of Linz” – was an obsessive-compulsive with a counting mania. This is true; but perhaps the reason his monumental compositions appeal so much to those of us seeking a transcendental escape from the strictures of time is that they were the composer’s own route to peace of mind, a way of fleeing from the terror of having to count every passing second, each infused with its own awesome significance.

Of course, the most productive way to challenge the faceless man with a scythe is to fill the unforgiving minute: when someone is working hard, he or she during that time is entirely focused on the job in hand, devoid of self-consciousness and doubt. That is why unemployment is so destructive of character and why Sigmund Freud described happiness as a combination of love and work.

Yet one of the consequences of successive technological revolutions, of which the information-processing one is just the most recent, is that we have much more leisure than those who went before us. It may seem as though we have less time to spare, but the opposite is the truth. Modern man needs spend a fraction of the time and effort that his forebears did to find food and warmth; and so has much more scope to harbour existential anxieties.

Lucky

By some accounts, this has created a sort of decadence in the developed world, a lack of appreciation of the simple joy of being alive. It is in this spirit that my wife reprimands me if ever I complain about feeling older. She refers to her great-uncle, who lies buried at the Menin Road South Military Cemetery, killed in action at 21 and posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. Our generation escaped the horror of world war; and aside from the families of professional soldiers in active service, it is only the autonomous failure of our own bodies that we need to fear, rather than the deliberate actions of others.

Even in this context, however, I am guilty of lack of gratitude for advancing middle-age and increasing grey hairs. Cancer claimed my mother at the age of 48 and one of my sisters at 32. The one never saw her grandchildren and the other did not even live to have the children she had so wanted (she had become ill in her twenties). When I think of them, I do feel lucky to have reached the age I have done, and comprehend the self-indulgence of moaning about the inexorable passing of the years and the accompanying prospect of decay.

For all that, I find it hard to accept, especially when I go to see my elder daughter, now at the same university I attended 35 years or so ago. Almost everything about the place seems the same as it was back then; and, when walking down its ancient streets, I can feel myself back into my late teens. Then I catch a shadowy image of my real form in a shop window’s reflection and am instantly disabused of that conceit.

Time to listen to some Bruckner: either that, or to grow up, however late in the day.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments