A night at the ballet can teach you more about British values than any harebrained political campaign

At the Royal Albert Hall were all the reminders one needed that English culture is a many splendour’d thing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was while I was watching Juliet deliquescing exquisitely into the arms of Romeo at the Albert Hall the other night that I realised what was wrong with the Government’s campaign to promote the teaching of British values. If we are concerned about the inculcation of values inimical to our way of life and habits of mind, the answer is not to replace them with values of our own but to dispense with the promotion of values altogether.

I learnt recently of the death of my sixth-form history master, a man I liked and admired and learnt from. When I heard, I held a little vigil for him in my heart. Of his appearance, the way he swung into class in his gown, how he would stand by our desks to clear up misapprehension, the conscientiousness of his teaching, the encouragement he gave and the jokes he cracked, I still remember much; but of his saying anything about values I remember nothing. A great deal was of course implicit in the way he taught and comported himself: the importance of knowledge and an open mind, good manners, kindness, patience, tact. That these were admirable qualities was something we learnt from his example, not from precept.

This went for all our other teachers, though some were more the exemplification of virtue than others. If we wanted to know what sarcasm and sadism looked like, we didn’t have to go much further than the gym, the one place in the school where an attempt was made to instil values – the value of not being frightened to break your neck on a vaulting horse. Self-defeating admonitions, all of them; to this day I hate exercise as a consequence of the value our gym teacher imposed on it. Otherwise, school assembly and “Gaudeamus Igitur” aside, staff kept their principles to themselves, except for the time an English teacher told us that Saturday Night and Sunday Morning was a flawed novel because it heroised a tax-dodger. Thereafter we never trusted a word he had to say about literature.

In deriding Cameron’s call for British values, many commentators have simply argued for their own. No high Tory jingoism for me, thank you, but radical intransigence, protest, the Tolpuddle Martyrs. Well yes, that too. The history teacher I’ve spoken of introduced me to Cobbett and Francis Place and the great tradition of English radicalism. Here it is, he said. Nothing more. He also introduced me to Burke. And Dr Johnson I’d got to on my own. Many are the voices that create a nation’s identity and it’s impertinence to make the ones that appeal to you the standard. Those who say it is precisely in the contrariety of voices that we are most distinctly ourselves speak the truth. As do they who argue that it’s by studying English literature that we find who we were, who we are and who we continue to be – always assuming that English literature continues to be taught.

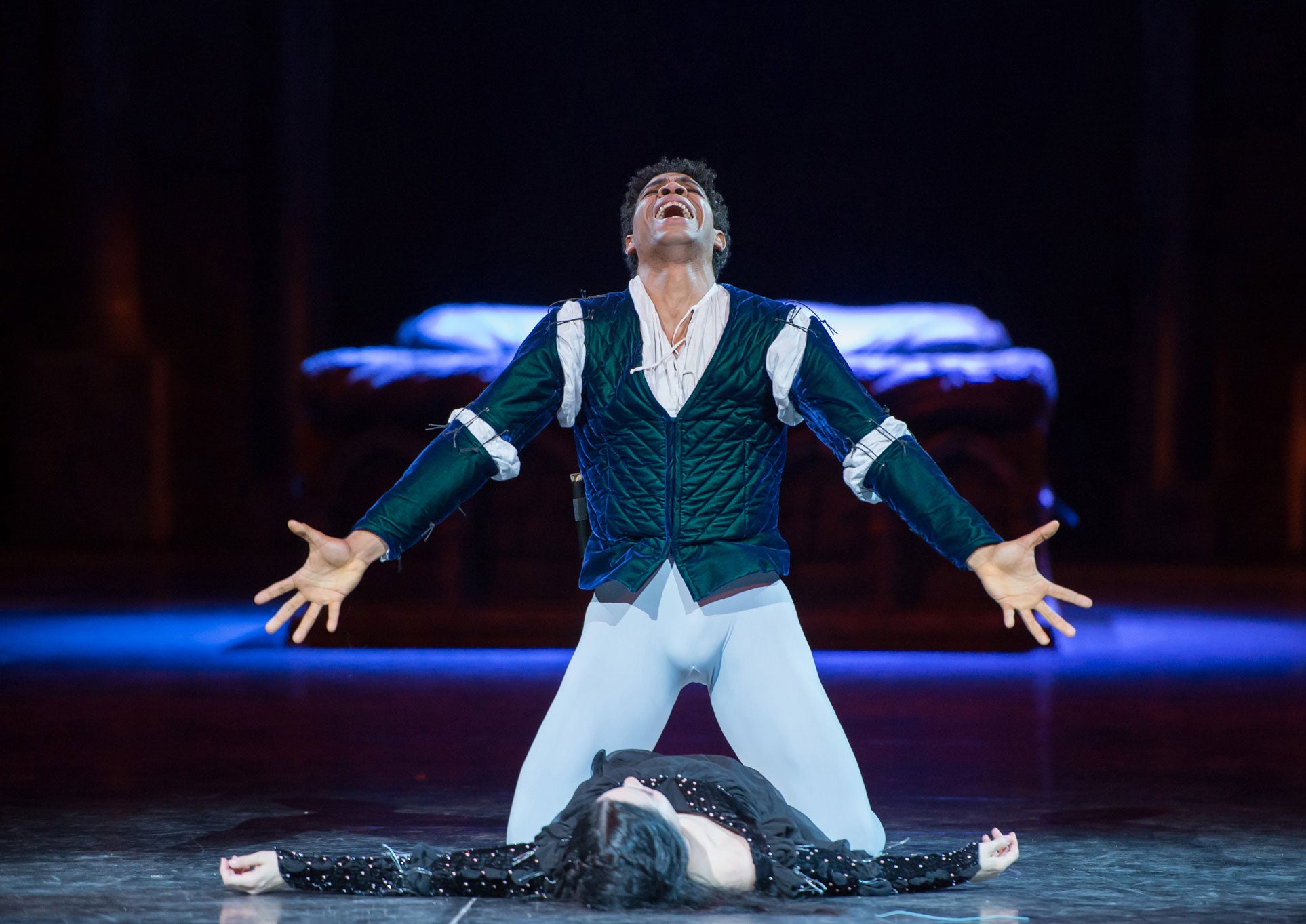

But the contrariety argument, though essential when combating single-value schools, isn’t enough. It was the spaciousness of art, its possession of a sphere a thousand times more liberating than any system of beliefs can hope to occupy, that was brought home to me as I watched Tamara Rojo dancing with Carlos Acosta at the Albert Hall. Here is not the place to sing their praises, but Tamara Rojo dancing rapture, reader, Tamara Rojo dancing abandonment, Tamara Rojo dancing oppression, Tamara Rojo dancing desolation, Tamara Rojo living every torture of carnal love in a body more sensitive than the imagination of a poet and more subtle than the mind of a philosopher – these were moments to raise any believer out of the iron chains of faith, had he only risked his immortal soul and gone along to see her.

Sitting in a hall named to commemorate a German, listening to music by a Russian, watching Spanish and Cuban-born dancers interpreting a ballet based on a play whose story Shakespeare had lifted from Italian sources – yes, here were all the reminders one needed that English culture is a many splendour’d thing. I’m not talking multiculturalism with its covert self-dislike. I’m talking the generous openness of the English to genius of whatever origin. We sometimes level the charge of insularity against ourselves. It’s a calumny. Few cultures have quivered more responsively to strange and unfamiliar beauty.

But Romeo and Juliet at the Albert Hall offered a still grander refutation of values and those who hold them. And not only because it tells a tale of warring factions, minds closed by hatred, the savage cruelty of forced marriage, and the longings of the human spirit to choose, for good and ill, what emotions it will be stirred by. Like love, in whose name it operates, art makes a little space an everywhere. No great art ever shrunk an individual life. The antidote to alien sectarianism is not home-grown sectarianism – the antidote to sectarianism of all persuasions is art.

I feared the Albert Hall would actually be too big for Rojo and Acosta to dance to Prokofiev’s fraught music. But when the lovers danced with all that space around them, their abandonment to each other felt especially dangerous – you could see why Juliet’s family was alarmed – and in that danger one could more than ever chart the fearful incontrovertibility of passion. Pity whoever never felt like that. And then when the murderous oppression of the lovers’ clans made love a hell for them, that too was of such enormity as would make the angels weep for loneliness.

All the reason and justification for art was here, a veneration for individual feeling, an evocation of the sacred as it’s perceived in lives lived, not imposed upon them. So teach art, not value. And wherever there is resistance to the teaching of art, wherever the child comes from a family that abhors and fears it, teach it more. Education has no higher aim.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments