A day to remember a different kind of conflict – ours with the natural world

Within a few decades the passenger pigeon was reduced to nothing

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There were two anniversaries on Monday September 1st. Both are momentous, but in completely different ways. It was the 75th anniversary of Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939, which began the Second World War, and also the 100th anniversary of the death of a bird in a cage in a zoo, in Cincinnati.

Until recent years, I suppose, it is only the first of these which would have attracted any attention, marking as it does the outbreak of the deadliest conflict in history, one which brought about the deaths of more than 60m people. What’s a bird in a zoo, compared to that? Yet in the decades since the Second World War ended, we have grown to appreciate the dangers of another type of conflict, which ultimately may be just as deadly: that between human society, and the environment which supports us. The bird that died in Cincinnati Zoo, at around lunchtime on September 1, 1914, is as potent a symbol of that clash as it is possible to find.

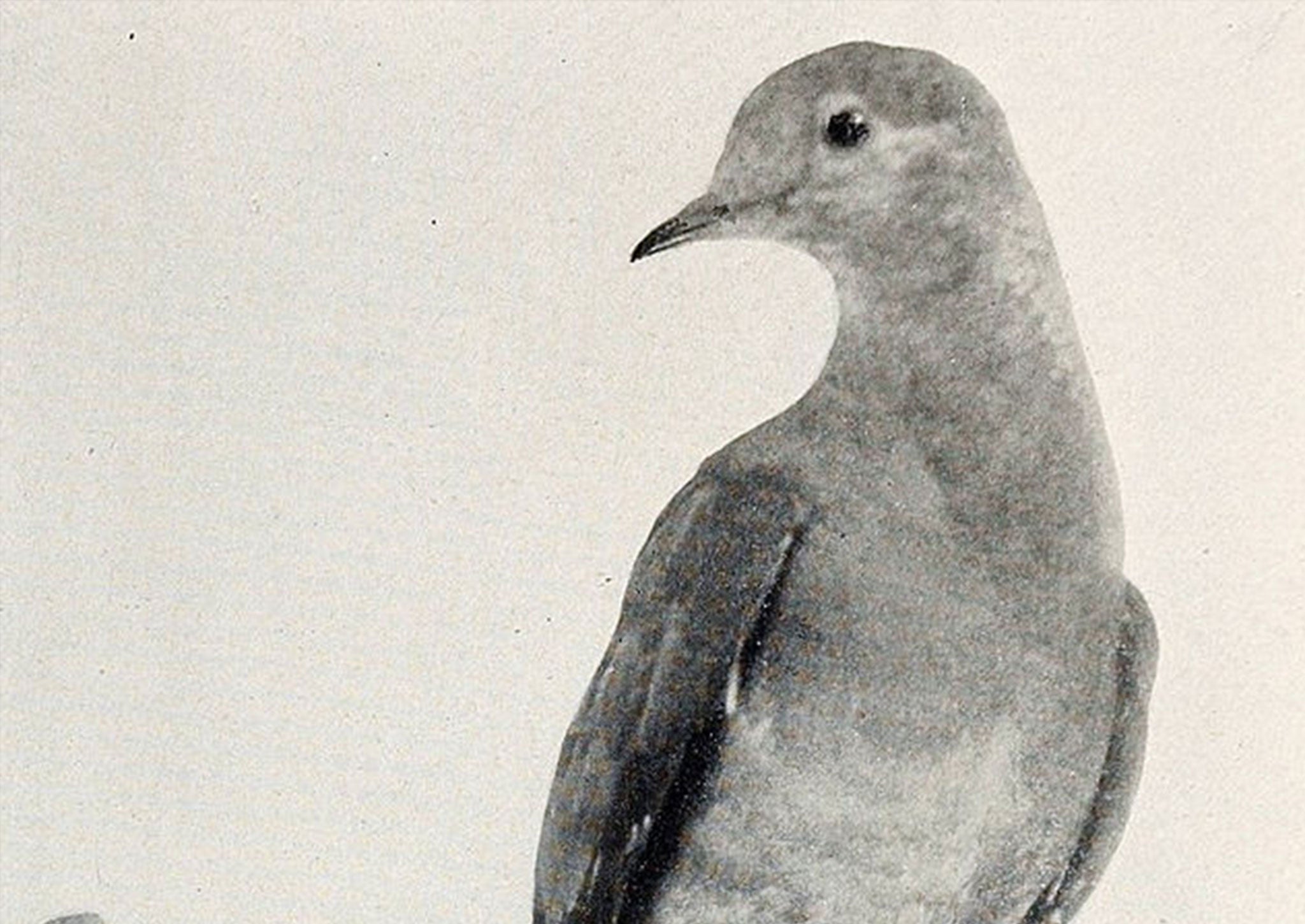

For the bird, christened Martha, was a passenger pigeon; and it was the very last of its species. With its death, Ecstopistes migratorius went extinct. Yet half a century earlier, it had been perhaps the most abundant bird on the planet, travelling in scarcely believable flocks that quite literally darkened the skies. Swarms of birds, numbering in the hundreds of millions, could pass overhead for hour after hour, sometimes even for days; the legendary bird artist John James Audubon carefully estimated the number of one astonishing multitude he witnessed at 1,150,136,000 birds, or in his own words, “one billion, one hundred and fifty million, one hundred and thirty-six thousand pigeons in one flock.”

Within a few decades, however, the species was reduced to nothing: from billions, to nil, in virtually the blink of an eye. How on earth could this happen?

The account of the passenger pigeon’s astounding demise is a cautionary tale par excellence for our society, as it lurches into the 21st century trashing nature with ever-increasing fervour. The story is unravelled by the naturalist and writer Mark Avery in his riveting new book A Message from Martha. It is a dark but fascinating chronicle of how human greed can have incalculable consequences in the natural world, which ultimately will be directed back at us.

For Avery documents with tremendous verve the gargantuan slaughter of the birds which took place in the second half of the 19th century: they nested in mammoth colonies, 200 nests to a tree, breaking the branches, and it was easy as pie for hunters professional and amateur to kill them by the barrel-load, indeed by the million, and ship them to the cities - especially as the railroad arrived. I for one had always assumed that this was the main reason for their downfall, and the mass killing certainly sped them on the way to extinction, but Avery reveals that the root cause lay elsewhere.

Insightful scientist that he is – he was the longstanding Director of Conservation for The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds – he explains that what really began their population slide was the remorseless destruction of America’s old-growth forests, as the pioneers pushed the frontier westwards. For the passenger pigeon had a highly specialised biology, and the great flocks were dependent on huge amounts of “mast”, tree nuts such as chestnuts and beech mast. Once the supply of mast began to falter, so did Ecstopistes migratorius.

By 1872, half of America’s original forests had been cut down, and the bird was probably already doomed, because its fall in numbers became self-reinforcing: its defence against natural predators had been the incalculable size of the flocks, and as they shrank, the predators did more and more damage, in a vicious cycle of decline.

Mark Avery travelled across America to uncover the evidence for this most extraordinary – and today, most relevant – of extinction stories and his account of his travels in search of Martha and her fate is as vivid as his account of the science behind it is absorbing. The book will be a wildlife classic. He ends by pointing to a British parallel – the much-loved turtle dove, which itself appears to be heading for extinction here. We couldn’t save the passenger pigeon, but can we still keep the turtle dove amongst us? Perhaps, but only if we listen to the message from Martha, who breathed her last a hundred years ago this week.

A Message From Martha – The extinction of the Passenger Pigeon and its relevance today. Bloomsbury, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments