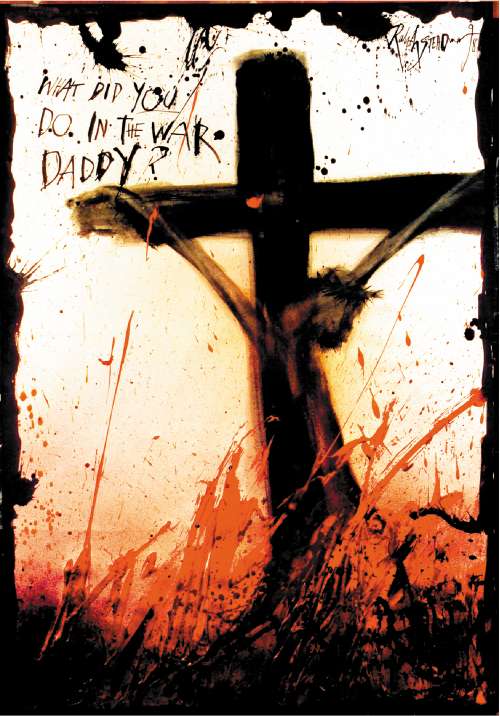

Will Self: PsychoGeography

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was a nippy February evening in Stamford, Lincolnshire. Meanwhile, inside the Arts Centre – which boasts a perfect little jewel of an auditorium – it was right toasty. Sitting in the dressing room, I idly read the Victorian playbills that were stuck up on the walls: "Miss Elizabeth Chitteridge playing the pianoforte, will be accompanied by a full orchestra, including local gentlemen on cornets and bassoons. Good fires will be lit. Stalls seats – two shillings." And so on.

I rather wished I would be accompanying Miss Chitteridge, rather than attempting to solo entertain a couple of hundred, with my own discordant wit: lugubrious readings from these columns, mad gags and heavily censored anecdotes. Some artistes have contract riders that specify they be furnished with a naked nymphet in their dressing room who has a gram of pure cocaine in the warm little cup of her belly button. Mine, by contrast, seems to insist on a platter of sandwiches – and they're always the same ones: prawn cocktail, egg mayonnaise, and cheese. I only ever eat the cheese, but hey, that's rock'n'roll for you.

Not that I want to diss Stamford Arts Centre: its staff were welcoming, but not egregious; professional, but not punctilious. The tech' guy, Keir, gave me a lift to Peterborough Station after the gig and confirmed my impression of the town as a small limestone-rendered bibelot, marooned in the Lincolnshire panhandle, where the most awful crimes are perpetrated by the TV units that come to shoot exteriors for Middlemarch and Pride and Prejudice. Oh, and the flasher – apparently there is one. He wanders down the High Street flipping his bits at the burghers – and that's got to be the quaintest thing about this quaint place: retro-crime; in any decent-sized urban centre this character would be raping and murdering.

I told the audience that I'd only been to Stamford once before. In the early Seventies I came with my dad to visit my godfather, Bartle Frere, who taught at the public school. Bartle picked us up from Peterborough in his pre-war Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost. I discovered which war it was pre- when I found First World War field dressings in the glove compartment beside the back seat. I didn't ask Bartle what he'd done in the Great War, although to my 12-year-old eyes he looked quite ancient enough to have fought.

He lived, together with his mother, in an enormous terraced house that backed on to the water meadows that run down to the River Welland. If Bartle was eccentric, the mother seemed completely spark-a-loco. She ran a small business making teddy bears in one of the upstairs bedrooms, and stumped up and down to it all day, perfectly active despite having one leg missing. The deficiency was made good by a curious prosthesis: two curved metal struts emerged from the hem of her tweed skirt, joining at the ground to form a wooden "foot". Halfway up there was a small box in which she kept her box of cheroots.

Well, there you have it: my only memory of Stamford, an anachronism within an anachronism. During the Q&A session at the end of the evening, one member of the audience observed that Mount Bartle Frere was the highest mountain in Queensland. Could there be, he wondered, a connection? Indeed, I replied. The mountain was named after Sir Henry Bartle Frere, one-time Governor of Southern Africa, who was my godfather's illustrious forbear.

As I signed books afterwards my head was all over the place. Mount Bartle Frere is easily visible from Tully in northern Queensland, a town that was the subject of one of the PsychoGeography columns I'd read that very evening. Could Stamford be the nexus of some strange psychogeographic current, pulling together time and place? After all, Bartle's Silver Ghost was an Imperial relic in the Seventies, and a century before his namesake had launched the invasion of Zululand that led to the dreadful debacle of Isandlwana – arguably the bloody high water mark of the project to turn the entire globe pink.

Then a middle-aged couple stepped forward in the line, and the man said: "Do you remember us? We're Paul and Lizzie; we were with you on the Magic Bus to Greece in 1977." Aaargh! Like the poor girl in The Exorcist my head began to whirl round and around while I spewed vomit over the shocked spectators and regulation Arts Centre watercolours. Not. But you have to concede: it was a little freaky. I looked at the handsome middle-aged couple, and slowly, the photograph of their younger selves was developed in my brain chemistry.

I'd been perfectly happy speculating on the odd linkages between one discrete happening and the whole warp of time, and weft of place. Now there was this hideous adolescent prolapse: an anachronism within an anachronism within an anachronism. I didn't stop shaking until I made it back to King's Cross.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments