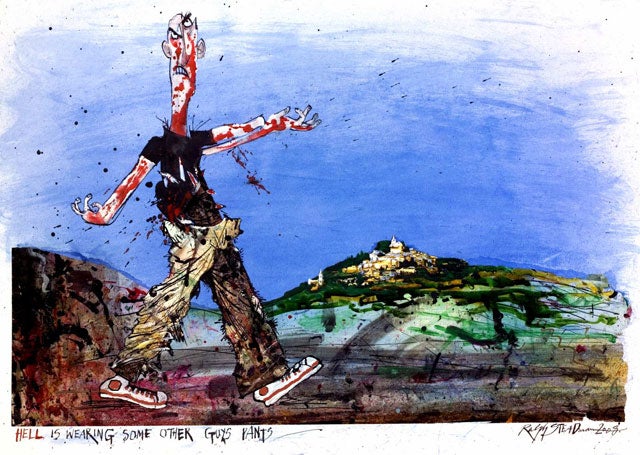

Will Self: A seer in Provence

PsychoGeography: The upland villages of Provence all look like mini collapsed towers of Babel

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."Hell" as Jean-Paul Sartre should properly have said, "is other people's trousers." I know this will sound odd to the speaker of American English, but in Europe to assert that "Hell is other people's pants" would leave one open to charges of filthy-mindedness, and possibly a visit from the authorities. Perhaps we'd best leave it as: "Hell is other people's nether garments", together with the hateful – but in this instance necessary – speech tic: "You know what I mean."

Or at least you should if you walk up small mountains – or large hills – that are also scaled by the multitude. Last year I was in the Provence region of France, and while I wrote about hiking across the Petit Luberon massif, I claimed that I'd cried off climbing the premier peak in the vicinity – the 1,914m Mont Ventoux – because to do so would be de trop. De trop for whom? I hear you ask, and the truthful answer would've been: for me. It was nudging 90 in the shade, and any time after noon the uplands became little infernos. The albedo of the limestone hereabouts is high to begin with, and under these conditions it reflects a diabolic radiation up the legs of your nether garments.

But this summer the weather had broken – and there was no excuse. I rose before dawn, cut a baguette into three chunks, buttered them, added chèvre to one, chorizo to the next, and left the third unfilled as part of a summit feast that would also include a whole roast quail and two beef tomatoes. Caffeine and nicotine ingested I took to my wheels, an underpowered Opel rented from Europcar in Marseilles. There was something more than apt about this – I considered, as, with a Gouda moon sinking behind me, I piloted the car east along the N100 to Apt – given that Opel, once a German company, was now owned by one of those weird pan-European car manufacturers that have sprung up over the past 20 years – Seat, or whomever – whose names are acronyms, while their cars are chimeras.

I had a CD of Bob Dylan's Theme Time Radio Hour on the car stereo, and he was spinning a platter that yodelled about "Waltzing across Texas". The mythopoeic world of American folk music is one of a radical heterogeneity, where one pays is altogether distinct from the next. In editorial after editorial American newspapers have a tendency to tell us Europeans to work harder – and it'll all be OK, but as my host, the writer John Lanchester, had pointed out the previous evening, the New World also accepts that the results of such graft will be wealth, certainly, but also greater homogeneity.

But this is a long established tendency. If I'd journeyed from where I was staying, Lacoste, the ancestral seat of the Marquis de Sade, to Mont Ventoux 230 years earlier, I would've passed not only through pays with distinct administrative systems, but also their own dialects. In 80 kilometres I would've gone from places where Comtadin – one local dialect of Provençal – was spoken, to those where Aptois could be absorbed; and on the flanks of Ventoux itself I would've heard pre-Alpine Gavot dialects chattering through the woods; suitable, really, given that the mountain is an outlier of the mighty range.

I only belabour this because while some contemporary writers take the poet Petrarch as their guide up Mont Ventoux, I preferred Bob Dylan. True, Petrarch wrote about his 1336 ascent – the first, he claimed, since antiquity – while Dylan has probably never heard of the place, but Petrarch, writing in Latin, was one of the globalisers of his day, while Bob – for all his ubiquity – remains a profound localist. Besides, Bob would probably have loved the drive, as the sun rose, and the maquis turned a greeny-gold. Maquis – mesquite, plus ça change ... Across the misty valley of the Toulourenc, the flanks of the mountain rose up, as blocky as any mesa.

The upland villages of Provence all look like mini collapsed towers of Babel: yellowy, seemingly friable houses; old, tip-tilted, and coextensive with the rock they stand on – Brantes was no exception. Here, I turned the Euromobile off the D40, crossed the river on a single track bridge, and drove through the hamlet of la Frache up to the parking lot by the Maison de Forêt. There was a guy there already but his nether garments weren't too bad – respectably full-length, neutrally coloured – I even muttered "Bonjour" before heading off along the track; and while I'd like to be able to tell you that he stared at me with blank incomprehension, not being a speaker of this alien Frankish tongue, the truth is that he amiably grunted like a sanglier about to charge the European Parliament.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments