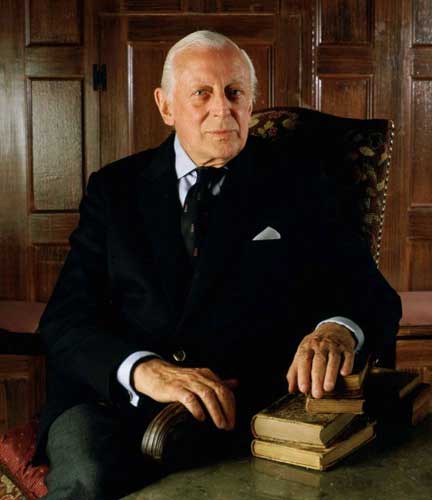

Tom Sutcliffe: The urbane power of Alistair Cooke

The Week In Culture

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Once, many years ago, I found myself in the BBC's old New York offices when Alistair Cooke was in to record his weekly Letter from America. The offices themselves were still in the Rockefeller Centre – one of New York's most elegant skyscrapers – and they commanded a pretty fine view of Fifth Avenue and St Pat's cathedral across the road. So, for a very junior producer, still a little excited at the discovery that New York really did have yellow cabs and steam coming out of the ground, the moment seemed a peculiarly intense distillation of Americana.

Outside the window I could see New York landmarks and, drifting down the corridor, that distinctive voice, which seemed to have become more transatlantic with every passing year. Being a very young producer, I took a rather dismissive view of what the voice was saying. At the time, I thought Cooke was a bit past it, and that the letter itself had long ago drifted into self-parody – an autumnal reverie that would wander slowly around the trophy room of Cooke's long career before turning you out at the other end, indefinably soothed but not necessarily much wiser.

I wasn't alone in thinking this, it seems. Just the other day, I heard Charles Wheeler expressing a similar view in an archive contribution to the BBC's centenary programme about Cooke, in which he suggested that Cooke had failed properly to report the violence of America in the Sixties and Seventies, but had smoothed its bitter divisions out of sight with that calm, equable delivery.

It's still a fair charge, I think. But I eventually came to believe that my youthful concentration on what Cooke was actually saying had slightly missed the point about the power of his broadcasts. And that was a view that was strengthened by listening to David Mamet's Alistair Cooke Memorial Lecture, which he delivered on Radio 4 the other night. Mamet's subject was notionally language, and I imagine that whoever had commissioned him hoped for something that would address – in the words of the old joke – the common language that divides us.

What they got instead was a contribution to a political debate that has stirred some controversy in the States but barely made the newspapers here. It concerns what's known as the Fairness Doctrine, an obsolete US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) measure intended to impose on American broadcasters something similar to the political balance requirements British companies have to observe.

Republicans dislike the Fairness Doctrine very much. Many Democrats rather wistfully pine to have it re-imposed, taking the view that unless they can rein in the shock jocks and Fox News they won't stand a chance of getting their message across. Mamet was against it, on the grounds that speech can either be free or fair, but it can't be both.

It wasn't so much what Mamet said that sharpened a sense of Cooke's qualities as the way he said it. In his only pronouncement on the Fairness Doctrine during the election, Barack Obama said he wouldn't back its re-introduction. But Mamet treated it as an imminent threat, even using the words "tyranny" and "police state" to drive home the hazard it represented.

He turned the heat up under the issue, in short, and he did it in language that rather self-consciously blended the demotic and the elite (if you use the word "polity" to describe society you're generally showboating). It was as unlike a Cooke broadcast as you can imagine – confrontational where the latter was civil, and urgent where the latter was urbane. Perhaps preferable, too, if there's really a fire in the house. But it made you see why Cooke's approach – there's nothing here we haven't seen before and won't see again, America will survive come what may – was such a popular way of serving up the news.

Look, it's Hitler's ghost

The Baader Meinhof Complex, Uli Edel's film about Germany's home-grown terrorist movement, offers a nice example of acting bleed-over – the phenomenon in which an actor's previous role unhelpfully colours your impression of the current one.

Bruno Ganz plays an open-minded intelligence man who takes on the task of tracking the group. He does it well, but I discovered that Hitler kept on interfering – partly because of the ubiquity of those YouTube mashups which draw on Ganz's performance as the Führer in Edel's film Downfall, about the last days in the Berlin bunker.

Every time he looked pensive for a moment I found myself bracing for an explosion of foam-flecked rage. Given that shame at the country's Nazi past was one reason for the Red Army Faction's alienation from the establishment, the presence of Adolf's ghost was distinctly jarring. Then again, perhaps Edel intended it all along.

Given the problems that Manchester City Council have experienced with Thomas Heatherwick's spikey sculpture B of the Bang, culminating in the payment of £1.7m in damages, one can only hope that the United Nations has a good contract for the £15m ceiling (right) they've just unveiled at their offices in Geneva. Constructed by the Spanish artist Miquel Barcelo, it used more than 100 tons of paint and an aluminium structure to create the effect of multi-coloured stalactites. It's intended to resemble a mirage he experienced in the Sahel desert, when he had the sensation that the world was melting into the sky. All I can think is that there may be a tussle among delegates not to be seated beneath the larger spikes.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments