Tom Sutcliffe: Must we vote for poets?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Bad luck. If you haven't already voted in the BBC's Nation's Favourite Poet poll you're now disenfranchised. Polling closed on Tuesday of this week, and however much you want to do your bit to make sure that W H Auden, or John Betjeman or Philip Larkin are apotheosised as a kind of Beanie Baby of verse, it's too late. Results will be disclosed on 8 October and there's nothing, short of breaking into the Poetry Society and going all Zimbabwe on the ballot boxes, that you can now do to affect the outcome.

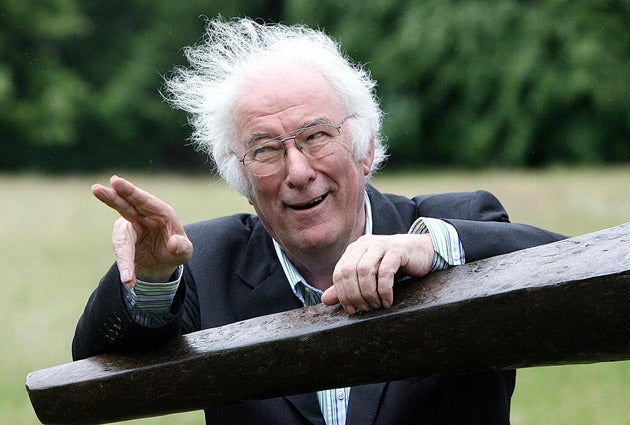

Personally, I'm not too worried that I missed my chance. As the previous sentence may have revealed to you, I don't think the idea of the "Nation's Favourite Poet" makes a lot of sense, and not only because I think that this particular expression of taste should be confined to liquorice allsorts and X Factor contestants. For one thing, there were only 30 poets to choose from, so anyone who bothered to tick a box on one of the websites was only registering a vote for "The Nation's Favourite Poet of Those Available". For another thing, that list seemed heavily, though not exclusively, skewed to the British Isles. There were two Irishmen (Seamus Heaney and W B Yeats) and two Americans (T S Eliot and Sylvia Plath) but otherwise it was GB all the way, as if the organisers had been determined to steer the vote towards a domestic champion. And there were the weird exclusions. How could such a list exclude Shakespeare? If seriousness was a problem, how come Eliot and Larkin made it it in, and Shakespeare didn't?

Mostly, though, it was the word "favourite" that got up my nose, with its suffocating implication of cosy, inoffensive, satisfaction. A public vote seems to offer itself as an audit of national taste, a means of finding out what sits at the heart of our collective attitudes to poetry (as if we actually had any), and yet the word "favourite" is a repudiation of any properly deferential relationship between a reader and a poem. There is a condescension embedded in its etymology, the faint sense that if Wendy Cope, say, should win, she will have been favoured by us rather than the other way around. Princes have favourites, but princes' favourites are always aware that favour can be arbitrarily withdrawn and that something is expected in return for admission to the inner circle. A favourite must flatter and please.

You could argue that I'm making heavy weather of a silly-season bit of space-filling. Most of us privately have our notions of literary and poetic favourites and would probably even recognise that those favourites say something about us. It's why its part of the standard boilerplate on social-networking sites to run up a list of your favourite books and groups, so that others can discover how much your Venn diagrams overlap. That solipsism, though, is the problem. A vote – and accompanying debate – about the Best British poet might (it's a long shot, I agree) tell you something about what is thought to constitute literary merit. The result of such a poll probably wouldn't tell you anything more about our cultural assumptions than the result of the Nation's Favourite Poet – but the discussion about what "best" might actually mean and what might be called as supporting evidence would at least turn you back to the poems.

A vote on one's favourite poet, on the other hand, is impervious to argument. I can legitimately make the case that Benjamin Zephaniah isn't the best poet in Britain but I can't legitimately argue that he isn't your favourite, since all you have to do is insist on the fact. Added to which is that deadly implication that a favourite poet is something to cuddle up to, when the best poems leave you less at ease with yourself rather than more so. I don't give a damn who the Nation's Favourite Poet is but I'd be interested to know who might be voted the Most Unsettling Poet.

Irony of the grim reaper

It was intriguing to read that Dominick Dunne's family had withheld the news of his death in the hope that his obituaries wouldn't be overwhelmed by coverage of the death of Edward Kennedy. Intriguing too to speculate about the commentary this mortal coincidence provoked in the Kennedy household – given that Dunne wasn't a very popular figure with them, on account of his coverage of the William Kennedy Smith rape trial, and his novel A Season in Purgatory – based on a notorious murder case involving a Kennedy relative. Dunne was credited with being largely responsible for the conviction of Michael Skakel for the murder of his teenage neighbour.

The possibility that Dunne's passing might find itself eclipsed by Senator Kennedy's would have struck some family members as a grim poetic justice. Ironically the two men also ended up fighting for a literary epitaph – with F Scott Fitzgerald's line about there being "no second acts in American life" quoted in obituaries of both. Whether there are or not, it's clear that the drama isn't always over even after the curtain falls.

I went to see The September Issue the other day – a little sceptical that a documentary about the compilation of an edition of Vogue magazine could penetrate my leathery indifference to haute-couture.

In fact the film begins with Anna Wintour rather defensively acknowledging that many people find fashion ridiculous and proposing – somewhat implausibly to my mind – that this because they are secretly frightened of it. R J Cutler's film turned out to be terrific though – often very funny indeed but also with a heroine who came close to persuading even this sceptic that fashion shoots might be an art-form, rather than a very expensive form of advertising.

The heroine isn't Wintour but her creative director Grace Coddington – a woman who reacts as if a beloved family pet has been spatchcocked in front of her when one of her picture spreads is trimmed, but who also has such passion for her shoots – and such dyspeptic disapproval of the celebrity culture that governs the magazine – that you almost cheer every time she comes on screen. Even if you buy your clothes by mail order, don't assume you'll be bored.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments