The Year in Review: How the map of our culture was redrawn

How do you best map the cultural year? The conventional way is a kind of aesthetic Mercator projection, in which the irregular realities of the arts are smoothed out on to a single flat plane. Some of the resulting realms and territories are very large. Film has a landmass all to itself and Theatre and Books command imperial stretches of space. And, just as a Mercator projection stretches and squeezes in variable ways, the act of year-end summary means that some regions loom larger in diagrammatic form than is consistent with their heft in the real world. This is a moment for the Iceland of contemporary dance to expand its newsprint real estate.

The Mercator projection isn't how any human can see the world, though, which is viewed more intimately, and through various filters of memory and prejudice. The way we actually look back on the cultural year is more like that famous Saul Steinberg drawing of the average New Yorker's perception of the world: in which 9th and 10th Avenue fill over half of the perspective, with a thin strip of the United States just over the Hudson River, and Japan and Russia just visible on the far horizon. Time does some of the foreshortening here. Remember how large A Prophet loomed 11 months ago? And yet Jacques Audiard's sensational film about a young man's criminal education in a French prison – easily among the best films of this year – already seems to have dwindled into the distance so that The Social Network (also excellent) now looms much larger.

Personal experience can have the same effect. My own Steinberg projection of the year has a kind of Great Wall of China in the near foreground, composed of uncorrected proof copies of the 140-odd novels that were in contention for this year's Booker Prize – judging which entirely skewed my view of the landscape. On this side of the wall stands Howard Jacobson's The Finkler Question, which won, and on the other, out beyond even the Jersey shoreline, I can just see Joseph O'Connor's equally touching Ghost Light, the one book that would have made my final decision much harder (had I been a better advocate for its virtues than I proved).

On Steinberg's map the foreground is all detail and the middle ground a scatter of geographical place names. In my perspectival view, the states are mapped out with abstractions, within which cluster all kinds of event. There's a region marked out as Controversies, for example, not very large this year because the kind of explosive arguments the arts can ignite turned out to be thin on the ground. Sometimes you expected a bang which never really came, as was the case with Chris Morris's intriguing film Four Lions, a comedy about suicide-bombing which was preceded by much wary editorial but was succeeded only by laughter. In other cases the rows were real, as with the debate provoked when the 11-year-old heroine in Matthew Vaughn's Kick-Ass addressed a room full of villains as Jeremy Hunts (in the sense later popularised by Jim Naughtie), a moment that generated vexed editorial from both sides of the political watershed. Michael Winterbottom's intensely violent adaptation of The Killer Inside Me brilliantly captured the bleakness of the Jim Thompson novel it was based on but also provoked a fierce attack on the misogyny it depicted, which some viewers felt it didn't do enough to condemn. And the television writer Jimmy McGovern, for whom tabloid opinion columns are a kind of litmus paper to test whether he's touched the right nerves, got the result he wanted with a gripping drama about an army bully, one of the episodes in his series Accused.

Somewhere over where Steinberg put Canada, there's a big section marked Recession, too. Because this year it was increasingly plain that hard times are starting to bite into artistic sensibility. American novels did it best, with Lionel Shriver's scaldingly angry novel So Much For That conducting an autopsy into the fatal wounding of a couple's savings by their encounter with the American health system, and Jess Walter's The Financial Lives of the Poets, a funny, unnervingly plausible account of a redundant journalist who turns to drug-dealing to make ends meet. Oddly, Recession is also the location for a couple of the best arts exhibitions, because this was a year in which intelligent frugality began to make its mark. There were big-ticket shows that worked – most notably The Real Van Gogh at the Royal Academy, which revealingly linked the art to the artist's letters – but Cezanne's Card Players at the Courtauld Gallery and Close Examination at the National Gallery showed that small exhibitions, or those which draw on a gallery's own permanent collection, can have as much weight as the old-fashioned blockbusters. And there's a film here, too: Debra Granik's remarkable hard-scrabble thriller Winter's Bone.

On the left-hand side of the map, where Steinberg puts Mexico, there's an extensive region marked Performances, because this year the acting was often more durable in the mind than the film or play or series they were in. Nobody could seriously argue that Dion Boucicault's London Assurance is a theatrical classic, but this old warhorse of a farce offered Simon Russell Beale and Fiona Shaw the opportunity for a textbook display of comic improvisation. In film George Clooney found his perfect role in Jason Reitman's Up in the Air, that faint complacency about his attractions perfectly aligned to the plot. Meanwhile, Judi Dench was so magisterial in Peter Hall's Midsummer Night's Dream that it made you fantasise about the Prospero she could give, and Rory Kinnear took the awards with an excellent Hamlet. The one new play that seemed more than the sum of its (excellently played) parts was Nina Raine's Tribes at the Royal Court, evidence of a writer with a genuine feel for theatrical emotion.

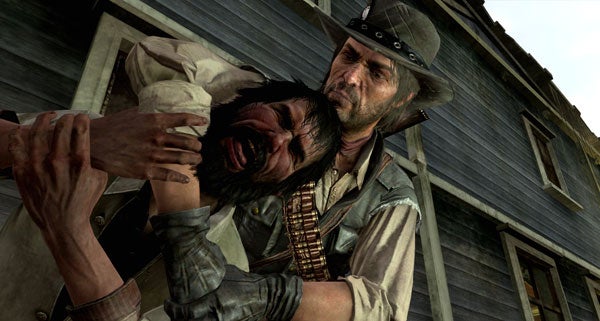

Beyond that, it's random saliences that remain as landmarks – the equivalent of the buttes and mesas which Steinberg has protruding from the tabletop flatness of his truncated Middle America. One marks the site of Christian Marclay's extraordinary video work The Clock (coming shortly to the Hayward, for those who missed it elsewhere). Another, fittingly enough, the engrossing south-western landscapes of Red Dead Redemption, a video game that edged the form one intriguing step closer to the standing of art. In the near distance there's Jeremy Sams' wonderfully funny libretto for Don Giovanni at ENO – refiguring Leporello's list song as a PowerPoint projection. And there, in the middle, the Ayer's Rock bulk of Radio 4's History of the World in 100 Objects, a concatenation of national treasures that included the broadcasting institution that made it and the museum that supplied the objects. Who won the Turner Prize? Sorry, it doesn't seem to be marked on this map at all.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments