The Weasel: High spirits

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

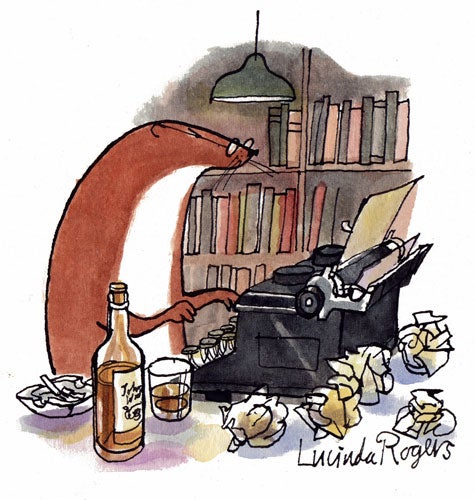

Your support makes all the difference.A couple of Saturdays ago in the paper that enfolds this magazine, you might have seen this intriguing Thought of the Day: "A man shouldn't fool with booze until he's 50; then he's a damn fool if he doesn't – William Faulkner, American author (1897-1962)." Admirably lacking in the sanctimony and Pecksniffery that tends to afflict similar maxims when they appear in other newspapers, this tribute to the life-enhancing qualities of grog produced a cheer in Weasel Villas. It would have been hypocritical, not to mention out of character, had any tutting emerged from my lips. It was not so long ago that I contributed a column entitled "101 Cocktails that Shook the World" that ran in this magazine.

Though Faulkner's view has much to be said in its favour, I'm more in accord with another of his coinages on drink: "Civilisation begins with distillation." (Maybe I'd switch the last word to "fermentation".) I learned this one from a small volume called Hemingway & Bailey's Bartending Guide to Great American Writers (Algonquin, $15.95). The two-man team (illustrator and writer) had plenty of scope. Particularly in the first half of the 20th century, drink and American writers went together like gin and vermouth. The guide gives a boozy anecdote, a drink-related quote and an associated cocktail recipe for 43 legendary US scribblers from James Agee (Whiskey Sour) via Raymond Chandler (Gimlet) and Dorothy Parker (Champagne Cocktail) to Thomas Wolfe (Rob Roy).

We learn that James Thurber (Brandy Alexander) said, "One martini is all right. Two martinis are too many, and three martinis are not enough." Dashiell Hammett (Martini) revealed, "Three times I have been mistaken for a Prohibition agent, but I never had any trouble clearing myself." Sinclair Lewis (Bellini) opined, "What's the use of winning the Nobel prize if it doesn't even get you into speakeasies?" When Scott Fitzgerald (Gin Rickey), during one of his rare dry periods, told the humorist Robert Benchley (Orange Blossom), "Don't you know that drinking is slow death?" he received the reply: "So, who's in a hurry?"

Droll stuff, but the tales of mishaps, protracted drinking bouts (60 straight hours in the case of Ring Lardner) and fights (a bust-up between Thurber and Hammett resulted in the cops being called to a speakeasy) reveal the dark side of drink. With many authors, the brevity of life-span is all the warning you need about following a writer's footsteps to the bar: Ring Lardner (Manhattan) 1885-1933; James Agee (Whiskey Sour) 1909-1955; Raymond Carver (Bloody Mary) 1938-1988; Hart Crane (Mai Tai) 1899-1932. Far from being a laugh-a-minute paean to the joys of booze, this is the only cocktail book I know that tells the unvarnished truth about the drawbacks of cocktails.

A yet more severe warning comes in Tom Dardis's book The Thirsty Muse: Alcohol and the American Writer, which fills us in on the consequences of William Faulkner's (Mint Julep) strenuous efforts to avoid being "a damn fool" after the age of 50. "Throughout the late Fifties, Faulkner was hospitalised every three or four months for drinking." Somehow he kept up his prodigious output, even producing one of his greatest novels The Reivers in 1961, unlike fellow writer and drinker Ernest Hemingway (Mojito), who "spent little time writing after the worldwide triumph of The Old Man and the Sea (1951)". Dardis finds "a kind of boozy sentimentality, visible on many pages". After "a frenzied period of non-stop drinking and carousing" while on a journalistic assignment in Spain in 1959, Hemingway lost the ability to write. He killed himself two years later.

Few will know the story of this fine writer's plummeting descent better than his grandson Edward Hemingway, who contributes enjoyable caricatures to the Bartending Guide to Great American Authors. In their introduction, the authors refuse to draw any conclusion about the relationship of alcohol to literature in America ("However pickled these writers may have been, they left an extraordinary body of literature behind for us"), though they do offer the following well-grounded words of advice: "Remember, a couple of cocktails doesn't make you a drunk, and no amount of liquor can make you a writer."

ith a tremendous wrenching noise, the Weasel household has swapped base from south London to the North Yorkshire coast, where we traditionally pass the summer. I use the last word loosely. On our first day up here, the Radio 4 weather forecaster announced: "Hot and sunny throughout England, with the exception of the north-east coast, which will be affected by a sea-fret or haar, but I suppose you'll be used to that." Well, not exactly. It still comes as a bit of a surprise when you find yourself wiping your specs, turning on your windscreen wipers and even donning a pullie when the rest of the country is roasting.

Surely one of the most colourful terms in meteorology, "sea fret" apparently derives from "fret" being used in the sense of "gnawing or eroding" as in "fretting away" at something. It might be scientifically erroneous to view a sudden mist as an eroded portion of sea, but if a fret creeps up on you while you're swimming this is exactly what it feels like. The Scottish term "haar" (perhaps from the Dutch word "haar" means hair, mane or "mass of filaments") is possibly even more evocative, particularly when an exclamation mark is applied afterwards. At one time, mariners said little else.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments