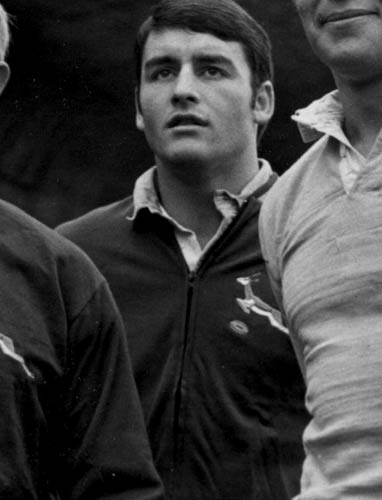

H.O. de Villiers: 'Rugby was like a religion'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sport is synonymous with South Africa. It goes deep into the psyche of its citizens, runs like blood through most South Africans' veins.

Yet the price paid by some outstanding exponents of the sportsman's or woman's art is often ignored. In an era when a player like Percy Montgomery can pass 100 caps for his country, a notable achievement, one of Montgomery's predecessors in the Springboks' No. 15 jersey limped stiffly into the hotel to meet me.

It's not that H.O. de Villiers is in bad shape, far from it. At 63, he has a healthy head of hair, beams bonhomie and plays golf regularly. But this is a man who retired a long time ago, back in 1970, after getting injured on the Springboks' 1969/70 tour of Britain and Ireland. He damaged his right leg, tearing the ligaments during a practise session and needed a total knee re-construction. Alas, the damage he had done and the experimental surgery that was attempted, prevented him playing any more Test rugby, hard as he tried to make a full recovery.

Then, five years ago, he had a complete knee replacement. As of today, he has also had both knees and both hips replaced.

In all, since his retirement, de Villiers has had 17 operations on his right leg. These are the hidden costs of the top sportsmen's trade. It's enough to make you wince, but de Villiers smiles. "I am now better than I was 13 or 14 years ago when I was really struggling" he tells me.

De Villiers played 14 Tests for South Africa between 1967 and 1970, and 29 matches in all for the Springboks. He was regarded as a ground-breaking full-back, a No. 15 who loved to get into the back line, attacking and running with ball in hand.

But of course, it was a different era. "90 per cent of the guys were working people in my time and the other 10% were students. The time we had for training was far less than now. I thrived on practising; I lived for rugby. I'd say my biggest regret is that I never played in the professional era where the training is so much more sophisticated."

And the treatment of injuries? It goes without saying, that side of the game is vastly improved. But the dangers of the modern game are obvious. If players like H.O. de Villiers, enjoying his sport in an era where the hits were nowhere near as hard and intense as today, could be injured so badly that, one way or another, the legacy has dogged him for the rest of his life, what might the present crop of players suffer? Will not the high speed impacts of far heavier, more muscular human beings take a shocking toll in the future?

Of course, we who sit smugly and safely on the sidelines, marvel at the crunching collisions, the horrendous hits. They elicit a collective gasp; they invite a gaping study by us ghouls. But perhaps we should be more mindful that, even though the young men in question are now handsomely remunerated for their efforts, even that may pale into insignificance in the years to come should they suffer the kind of constant medical problems endured by H.O. de Villiers.

He makes the point that very few threequarters today playing international rugby are under 95 kgs. Indeed, take the example of two centre threequarters in South Africa and New Zealand. The Springbok Jean de Villiers weighs 100kgs, his New Zealand counterpart Ma'a Nonu, 104kgs. A flat out, heavyweight impact between the two means a collision of 204 kgs, at pace. Long term damage must ensue.

Yet as H.O. de Villiers says, he was regarded as one of the biggest guys of his time and he weighed 85kgs. However, to balance the equation, players today are better prepared and obviously fitter. And the management of their injuries is so much more professional.

"After one operation, I was in heavy plaster of Paris for three and a half months" remembers de Villiers. "It took months before I could even bend my leg properly.

"So players of course get the required professional attention much quicker today. Yet even so, there will be some sort of a price they have to pay in later life, it is inevitable. It's the same as a boxer: you take the pounding and it doesn't really matter how well prepared you are. Every boxer is brain damaged, to some degree. Likewise, every rugby players' legs will suffer. Very few front row guys of years gone by that I know don't have hip or neck problems nowadays. The nature of the game says this is what happens."

For sure, de Villiers' words are correct. An acquaintance of mine, a girl who played women's rugby for the Bath club in England, had had a complete knee replacement by the age of 23. These are the sobering realities.

But naturally, there are considerable compensations. De Villiers' face is wreathed in smiles, like a crumpled up newspaper, at the memory of so many friends. "I met many wonderful people all over the world and saw so many great things. I would have it all over again if I could."

Of course, the 1969/70 UK tour that was to prove the demise of his career was hallmarked by the anti-apartheid protests. Students marched, banners were unfurled; hitherto law-abiding citizens sat down in roads outside the grounds and scuffled with police. These were astonishing times, yet it was a unique era. Little more than 12 months earlier, then French President Charles de Gaulle had prepared to escape the Elysee Palace in Paris by helicopter as the city seethed with rioting students.

For a boy who had studied at Dale College, King Williams' Town in the Eastern Cape to be plunged into the midst of all this, was some challenge. Alas, says de Villiers, the tour failed in a playing sense because a lot of the players could not adapt to the off-field disruptions.

"The preparation (for matches) was shocking, they just hid us away. The protestors surrounded our hotel at Peebles before the test match with Scotland and kept us awake all night, they were making such a noise. We'd get abusive phone calls in the middle of the night."

In Ireland, they were pelted with potatoes but never had a drop of Guinness thrown over them. The Irish don't believe in wasting the holy water. But how does de Villiers reflect now upon those times?

"Then, we asked ourselves, did those people know what they were demonstrating about? But now of course, you look back and think how could we ever have agreed with the apartheid system? My kids say to me, why didn't you question it and I admit, I find it hard to answer their questions. But I didn't know any better; we all grew up under the system. You went to school and everybody in your class was white. You assumed black kids went to black schools.

"Only as you got older, you realised and thought about what was going on around you. Now, I look back and realise what a tragedy it has been for the country because of all the un-education (sic) and brain power that has been wasted. It is a tragedy that it ever happened. But we were born into that society.

"As kids growing up in South Africa in those days, rugby was like a religion and you only dreamed of playing for your country. When I was five years old, I went to a fancy dress party and my mother dressed me as a Springbok rugby player. My little friend was dressed as an All Black. It was an obsession."

Mind you, this was no kid born with a silver spoon in his mouth. De Villiers' came from a very modest background. His father worked for an insurance company for 44 years and young H.O. played all his junior rugby, for Worcester Boys Primary School Under 12s, bare footed. Kicking at goal ? "That was bloody difficult" he smiled, wincing at the memory………

"We would be out kicking the ball at 0845 in the morning, bare foot, on a freezing school field. Some guys broke their toes trying to kick the ball because you never kicked with the in-step in those days."

De Villiers' example ought to be a stirring siren to a lot of young rugby players of contemporary times. "I thought rugby was my life but when I got injured I looked around and thought ‘I have nothing'. Suddenly, I had to go and find a job but I hadn't gone to University and wasn't qualified."

Eventually, he found his way into the insurance business and spent 30 years in it. In his spare time, he coached the Villagers club in Cape Town and also a school in the city, SACS, where one day he met a very polite young pupil whom someone said might become an excellent rugby player.

"I coached Percy Montgomery for his last three years at SACS. There was no question even then; you could see he would be a great player. He was a star in the school side. He grasped everything so fantastically well. You would just suggest something and he would latch onto it."

And, like so many others in the life and times of H.O. de Villiers, his friendship with Montgomery stayed strong. For most of Monty's 100 plus caps, his former mentor called him prior to each game, offering encouragement. His own playing career may have been all too brief but H.O. de Villiers' role as Montgomery's mentor was crucial to so many Springbok successes down the years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments