John Walsh: No one has a monopoly on the truth about the King of Porn Paul Raymond – including his son

Notebook

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For schoolboys in 1960s London, the words "Raymond Revuebar" conjured up a world of head-spinning wickedness. They – and a tacky flashing neon sign of a dancing nude – were the beating heart of Soho when it was still gratifyingly seedy and deliciously decadent.

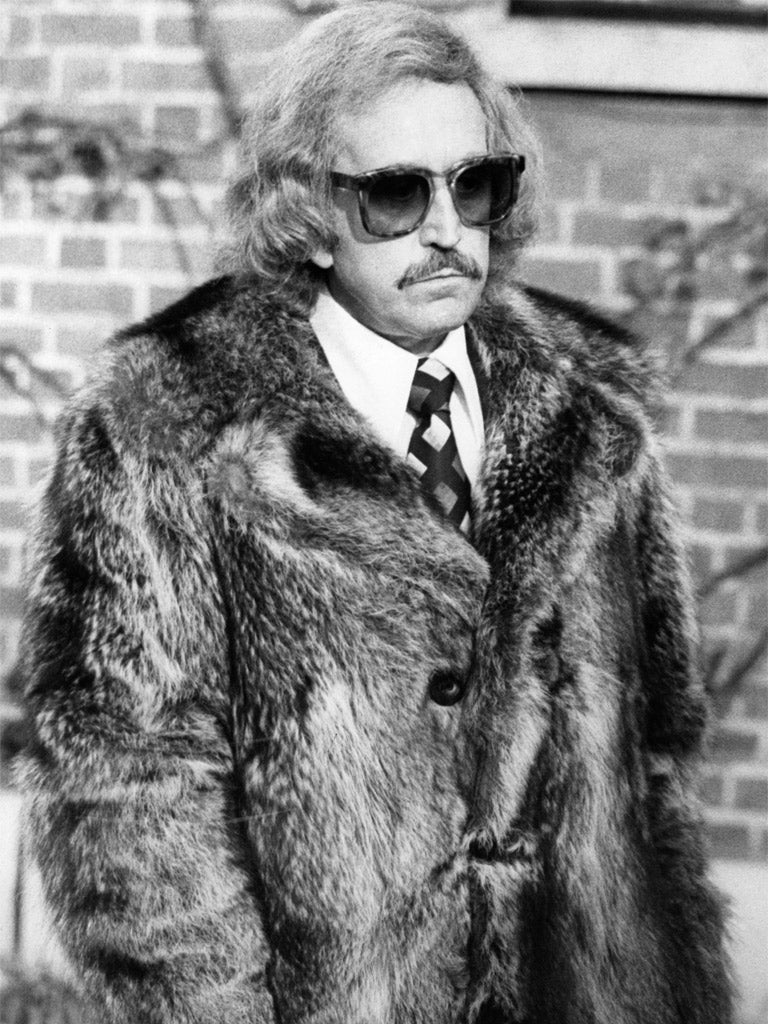

In the grid-lanes off Shaftesbury Avenue, they promised striptease shows, a blizzard of breasts, a dazzle of diamante G-strings, platoons of semi-naked girls performing with snakes or drugged panthers. The audience allegedly featured respectable chaps like politicians, cheek-to-cheek with career gangsters and bent coppers. Behind the carnival of smut lurked the faintly comical, long-faced, long-haired figure of Paul Raymond, a Catholic boy turned stage clairvoyant turned impresario of flesh, the Murdoch of porn mags.

So when I heard, last year, that the director Michael Winterbottom was shooting King of Soho, a film of Raymond's life based on Members Only, Paul Willetts's marvellous biography, I thought: Yay. It was good to hear that Steve Coogan, star of Winterbottom's 24-Hour Party People movie, had been signed to play the sleazemeister – Coogan with his faintly reptilian charm and his petulant egomania. Anna Friel, Imogen Poots and Gemma Arterton were also involved as Raymond's wife, daughter and girlfriend Fiona Richmond. It sounded a treat.

Now look what's happened. Paul Raymond's son Howard has signed a deal with a studio to make another film about his dad – also called King of Soho, from his (Howard's) own biography. This week, he announced that he's signed up the handsome, patrician Tom (War Horse) Hiddlestone, who looks nothing whatever like Raymond, to play Raymond, and told the press, "It's about the private persona of our family, as opposed to the public persona."

Though he once had friendly discussions with Winterbottom about his movie, he's now rubbished it as a kind of Carry On spoof. "We call it Carry On Up Old Compton Street." He's also trying to get his lawyers to trademark the name "King of Soho", so that only his team can use it.

Here's the moral crux: does Raymond Jnr have more of a right to tell his father's "story" than a competent biographer like Willetts, who may be more likely to establish the truth about his subject? Is the son right to try to control a celluloid portrayal of his father, even down to patenting the title? Is he being a good son here, or a cynical, bandwagon-leaping opportunist?

The concept of the retaliatory movie isn't unprecedented, of course. A similar row broke out last month over Bob Marley. A documentary entitled Marley, by Kevin Macdonald and Chris Blackwell, was released to acclaim here and in the US. When a second film, Bob Marley: the Making of a Legend, was premiered at Cannes, its director Esther Anderson, an old girlfriend of the reggae titan, complained that lawyers representing the rival movie had tried to stop her making the film. She's now talking of suing them for using her footage without her permission.

In years gone by, retaliatory biographies weren't unknown. Cyril Connolly's widow Deirdre flatly refused to let anyone write her late husband's life – until, in the 1990s, a scoundrel called Clive Fisher decided to go ahead without her permission, whereupon she instantly commissioned an authorised biography from someone she could trust, Jeremy Lewis.

But behaviour like Howard Raymond's is not an edifying spectacle – and, of course, it's counter-productive. Faced with the choice of an intimate family hagiography of the "private" man, or the vivid spectacle of the "public" Raymond – who once had to rescue a stripper ("Miss Snake-Hips") from the near-death squeeze of a boa constrictor he'd saddled her with – I know which the public will rush to see.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments