Carolina's Lost Colony: The fate of the first British settlers in America was a mystery... until now

Out of America: They arrived two decades before the Mayflower landed in Massachusetts, but the 115 colonists then vanished

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There are places, on America’s mid-Atlantic seaboard, where you can still imagine the coastline as the first English settlers must have seen it, more than 400 years ago. No boat marinas, no highways, no beachfront houses for rent: just reeds, marshes and shimmering expanses of water where the sea meets the sky, and the hazy outline of pristine forests.

So it must have been when John White returned to Roanoke Island for the last time. He was well acquainted with the area – part of what is now North Carolina, guarded by the barrier islands today known as the Outer Banks. White had made a first reconnaissance mission there in 1585. Two years later, he was back, as governor of a new permanent colony sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh. But the going was hard, and soon White sailed back to England to organise further supplies.

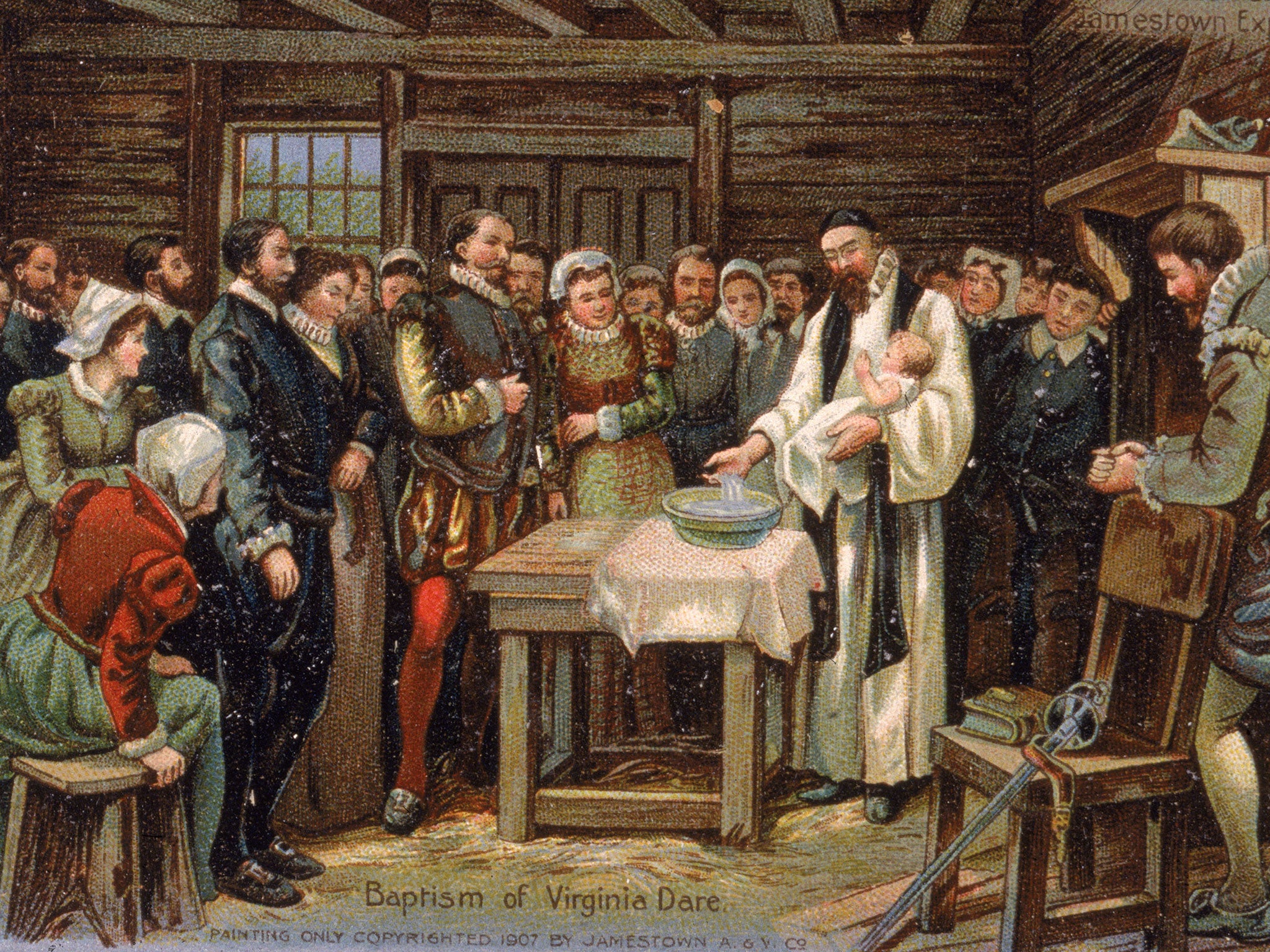

Unfortunately, there was the small matter of the Spanish Armada to contend with. No ships were available and the fate of a few score intrepid settlers at the rim of the known world was of little import compared with the survival of the Queen’s realm. Only in 1590 could White return to Roanoke. But when he got there – nothing. The 115 colonists had vanished, among them his own daughter and son-in-law, and their infant daughter Virginia Dare, the very first child born to English settlers in the New World, on 18 August 1587.

But what had happened? The departure seemed orderly. The buildings had been carefully dismantled; the only clues left were the letters C-R-O-A-T-O-A-N carved on a post, seemingly a reference to Croatoan, the old name for Cape Hatteras, the extreme southeastern point of the Outer Banks, 50 miles to the south, or to the Croatoan Indians who inhabited coastal North Carolina.

Thus was born the saga of the “Lost Colony”, a mystery for the ages that still provides welcome distraction to American children plodding through their country’s history. Theories abound: that the colonists were slaughtered by hostile Indians; that they died of famine or disease; that they were assimilated, voluntarily or involuntarily, by tribes; even (this being America) that they were abducted by aliens.

But in the most basic historical terms, Roanoke matters. The settlement, whatever its fate, was the first established by the English in North America, predating Jamestown by 20 years, and the arrival of the Mayflower on the hard shores of Massachusetts by more than three decades. Like Jamestown, the colony was a commercial venture, designed to exploit the vast imagined riches of the New World. Instead, it disappeared from the face of the earth. Until now, that is.

For many years, archaeological digs around Hatteras have yielded some tantalising clues: coins, gun parts, a signet ring and various other artefacts from the 16th and 17th centuries. But the real breakthrough came in 2012, as the British Museum scrutinised a watercolour map in its collection called Virginea Pars, on which John White apparently started work in 1585, during his first visit to the area.

The map itself is both beautifully executed and remarkably accurate. What followed, however, might have been lifted from Treasure Island. In the middle of the map, some 50 miles west of Roanoke, is a patch. Using imaging technology, museum experts found that beneath the patch was a blue and red star, possibly denoting a fort.

The location, on the edge of the mainland on the other side of Albemarle Sound, more or less fitted in with a reference that White himself made later to an intended and more permanent destination, about which the new settlers were talking as early as 1587. Why the spot had been covered by a patch is a mystery in itself. Perhaps it was to keep such a plan, of obvious military significance, secret from Spain, then the leading colonial power in the Western Hemisphere.

So, the researchers focused attention on an impoverished corner of North Carolina called Merry Hill, notable mainly for an Arnold Palmer-designed golf course. The area, called Site X, had been looked at before, but this time the digs yielded some particularly telling finds. Last week, the First Colony Foundation, the group which has been sponsoring the excavation, provided the first details.

No evidence of a fort has come to light, nor of the “Cittie of Raleigh” that the Elizabethan courtier-adventurer-poet intended as centre of his project. But the location makes sense, strategically placed at the confluence of two rivers. And the items unearthed by the archaeologists fit in with the period, including bits of guns, a nail and an aglet (a small metal sheath protecting the end of shoelaces) – and, above all, fragments of a type of English pottery known as Surrey-Hampshire Border ware, of which shipments to America stopped in 1624 when the Virginia Company of London was wound up.

None of this amounts to conclusive proof. The discoveries, however, are the most credible suggestion yet that the “Lost Colony”, or part of it, survived after 1587 and after Roanoke, for a while at least. Scholarly opinion is now shifting from the view that the settlers were simply exterminated towards the theory that they were assimilated by neighbouring tribes – this would bear out local lore, about the odd native who was strangely pale-skinned and blue-eyed – and that perhaps the settlers split up, with some heading south to Hatteras, and others moving west to Site X.

There, for now, matters rest. But as so often in attempts to unravel remote history, one discovery leads only to new hypotheses. What, for instance, happened to the settlers once they got to Site X? As Phillip Evans, president of the First Colony Foundation, almost reassuringly puts it: “The mystery of the Lost Colony is still alive and well.” And on both sides of the Atlantic, for in St Bride’s Church, off Fleet Street in London, you’ll find an enigmatic bronze of the child Virginia Dare, in the very place her parents married, before the voyage to the New World from which neither she nor they would return.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments