Wales voted for Brexit because it has been ignored by Westminster for too long

Wales as a whole is not having a conversation about its identity and existential relationship with Britain in the same way that Scotland is – this means that the Welsh public weren't engaging in the referendum on Welsh issues

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

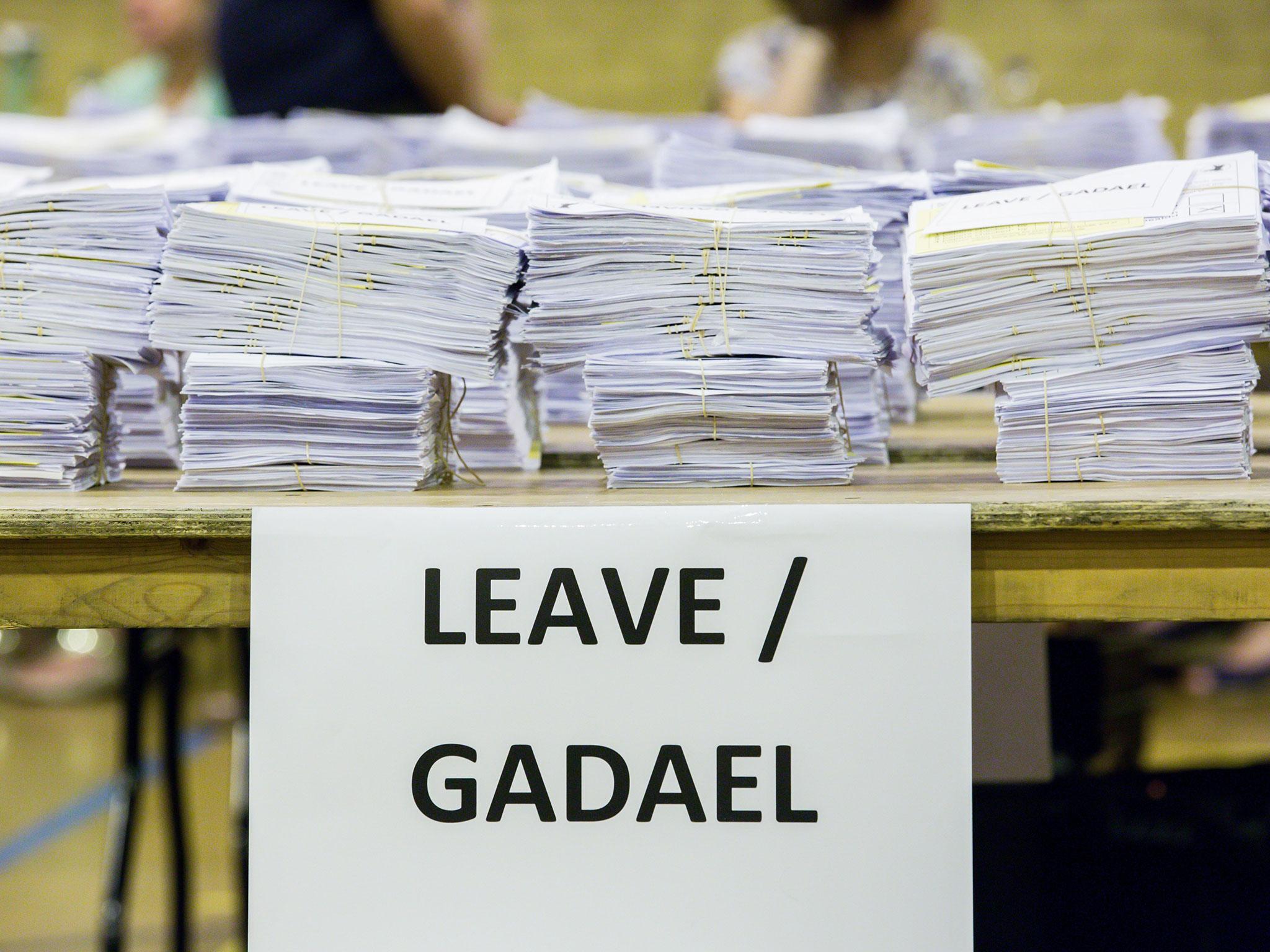

Your support makes all the difference.“Twrcyn pleidleisio i Nadolig”. That’s how you say “turkeys voting for Christmas” in (broken) Welsh – a sentence that might come in handy at the moment, as it transpires that Wales has voted 53 per cent to 47 per cent to leave the EU.

Why would a nation that receives £70 a head from the EU more than it puts in vote this way?

The first reason is not specific to Wales. A Leave vote was sold to the British public on the basis that it would allow us to “take control back.” What exactly that means was never spelled out in detail, but there’s no doubt that such a sentiment would appeal to Welsh voters, given that Wales is the UK’s poorest region and has been totally abandoned by mainstream politics.

To live in Wales, for many, means living in an area without stable, decent work and where the rest of the UK barely even registers your existence (particularly if you don’t live within easy access of Cardiff), and where you can expect to be treated as voting fodder by an historically dominant Labour Party. If “taking control back” means having some kind of agency to improve one’s living conditions, whilst also forcing politicians to actually pay attention to you, I might have been more surprised by a Remain vote in Wales.

But it’s also important that we don’t talk about Wales as having a single hegemonic culture. It’s home to Ceredigion, known as the most Europhile place in the UK, and my home council Gwynedd returned a Remain vote. Both of these areas are the furthest away from the English border, they have the most Welsh speakers in the country, and a strong tradition of Welsh nationalism. This transforms the way their populations see politics – as distinct from the rest of the country, and highly focused on local issues. When I was growing up in Gwynedd, it was more common to see xenophobia directed towards the English-born population (the largest migrant group in Wales) than migrants from further afield.

Having said that, anecdotally I understand many working class people in Gwynedd have been talking about “taking the country back.” There aren’t any figures on this yet, but it begs the question of whether Welsh nationalism risks being elided by a “Little England” narrative.

Other regions in Wales, particularly places in the south and the east, have experienced a similar industrial decline and waning of the labour movement as the north east of England.

Understanding why there is a Leave vote in those areas is not rocket science – although it should be noted that many parts of Wales have experienced an influx of English people in recent years, many of whom are right wing and will have bolstered the UKIP vote. These areas have fewer Welsh speakers and their politics are less defined by Welsh nationalism than areas in the west, making them vulnerable to right wing English politics.

The final and most important point (particularly for London-centric commentators who refuse to familiarise themselves with regional nuances) is that the political culture of Wales is significantly different to that of Scotland. As Dr Daniel Evans of the Wales Institute of Social & Economic Research says, “The main factor for me is lack of a national media or public sphere in Wales. This means that the Welsh public weren't engaging in the referendum on Welsh issues. Hardly any of the people we spoke to in our research knew anything about the EU dividend to Wales or the implications of Brexit for Wales. Instead they focused primarily on British issues such as immigration. This reflects the diet of media in Wales, which is the same as England. Scotland of course has its own media, a left wing party in charge, and revived engagement in politics since the Independence referendum.”

So, although there are highly localised political conversations in Welsh nationalist areas, Wales as a whole is not having a conversation about its identity and existential relationship with Britain in the same way that Scotland is. This means it has been unable to engage with the referendum distinctly as “Wales”, as opposed to an annex of England.

What we can learn from this is that progressive political parties cannot rely on the myth that Wales as a whole is more socially democratic than England. The Labour Party can no longer expect Welsh voters to obediently follow its instructions, unless it offers them something in return – acknowledging their existence would be a start. Progressives in Wales should resist the kind of hostile nationalism that has defined certain pockets of the country, but should look at building a kind of distinct Welsh identity against the meanness fostered by the Leave campaign. And Welsh voters should be worried. The unfortunate truth is Wales needed the EU to invest in it. It’s highly unlikely Boris Johnson and his ilk will compensate for the losses it will sustain by leaving.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments