The UK should never have let the EU get away with being both judge and jury for Brexit

The perception of weakness and division in our government only encourages the hardliners on the other side of the Channel in the virtue of their inflexibility

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

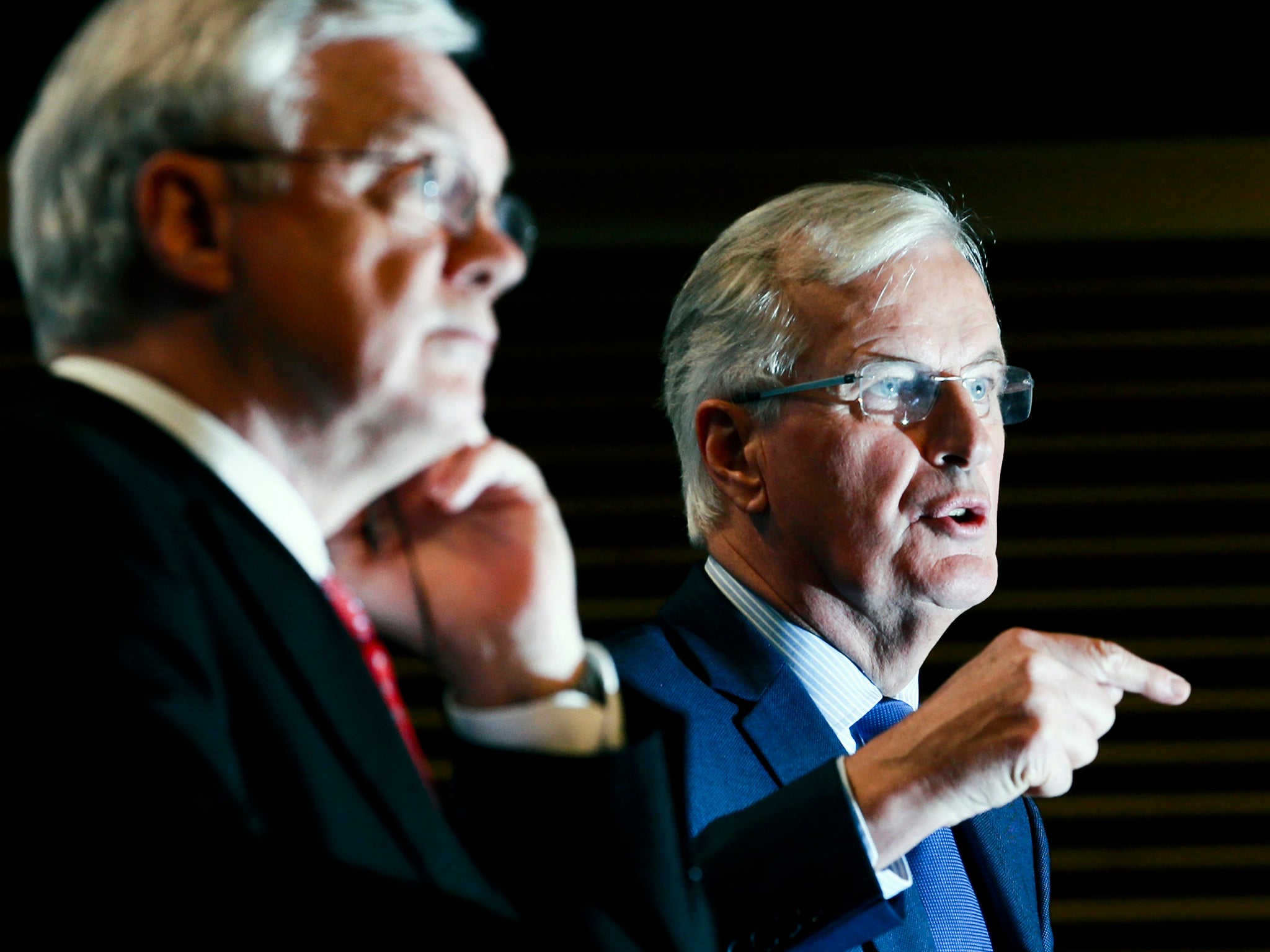

Your support makes all the difference.It was hard to experience a surge of optimism at the conclusion of the fifth round of Brexit talks earlier this week. At their press conference, David Davis was his usual “look on the bright side” self, while that elegantly attired Easter Island statue, Michel Barnier, blew both cold and tepid – but mainly cold.

He would not, he said, be recommending to next week’s European Council that there had been sufficient progress on stage 1 – citizen’s rights, Ireland and money – to justify moving to stage 2: the UK’s future relationship with the EU. He added rather menacingly that there had been a “disturbing” lack of progress on the divorce bill and that there would definitely be no concessions on any aspect of stage 1.

After this douche of cold water, there was a tiny flash of ankle when he added that decisive progress was “within grasp” before the end of the year. Brexitologists have jumped on this, and on stories of Barnier pressing for more flexible instructions from the Council, to suggest that the EU27 might be crawling crabwise towards talks about our future relationship with the EU. That may be so. But the logic of Barnier’s statement is that this will happen only if we make further concessions.

Of course, the Grand Guignol of British politics does nothing to help. The perception of weakness and division in our government only encourages the hardliners on the other side of the Channel in the virtue of their inflexibility. This, and the whispering of Tony Blair and his ilk into Jean-Claude Juncker’s ears, lead many of our continental friends to believe that, if they keep up the pressure, in the end we will bottle leaving the EU.

As someone who voted to remain, I yearn to escape the unforgiving Manichean nature of the British debate. We desperately need someone who has no skin in the Brexit game to help bring us to common sense – like an international relations expert from the planet Mars.

This creature would make three observations.

Firstly, a successful outcome is in principle eminently feasible, because it is so stonkingly obvious that it is in the interests of each side.

Secondly, it is hard to conceive of two more closely aligned negotiating partners, given that for the last 40 years they have, with few exceptions, adopted the same regulations, standards and directives. A UK/EU Free Trade Treaty should be a slim volume compared with the massive tome of the EU/Canada agreement, which Juncker so meretriciously took to his notorious dinner with Theresa May in No 10.

Thirdly, and perversely, the negotiations have been set up to fail.

The UK most unwisely accepted the EU27’s concept of a phased approach, in which they play judge and jury on whether sufficient progress has been achieved in stage 1 to merit moving to stage 2.

This is daft – daft to try to create a firewall between the divorce settlement and the future relationship when the two are intimately tied; daft to demand that the UK commit in advance to paying billions before talks on the future can start. This is a derivative of the calamitous Israel-Palestine negotiating playbook, where each side demands, as a precondition for negotiations, that the other abandon its most cherished negotiating objective.

In a normal negotiation, you put the subjects to be discussed in their respective baskets and debate them in parallel. Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed. That protects everyone’s interests.

The European Council adopted this very principle on 29 April this year. But it still insisted on the belt-and-braces of a phased approach, no doubt at the behest of those most concerned about the financial hole our departure would leave. May’s Florence speech has given sufficient assurances in that respect. The demand for greater precision on what we are willing to pay before moving to stage 2 is blackmail. The appropriate riposte to “no concessions” is “no deal is better than a bad deal”. No deal means no money at all for the EU.

Money is at the heart of the negotiation. It can be settled only at the end when everything else is clear. If all goes well, I can see that happening just before dawn at a European Council in March 2019, following a trilateral meeting between May, Macron and Merkel in a small stuffy room off the conference chamber. It was ever thus.

Sir Christopher Meyer is a former ambassador to the United States and Germany

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments