We cannot deal with Islamist terrorism alone. Using security as a Brexit bargaining chip is a dangerous game

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This is Theresa May in her Article 50 letter on a post-Brexit trade deal with the EU: “In security terms, a failure to reach agreement would mean our cooperation in the fight against crime and terrorism would be weakened.” Then we had Amber Rudd, the Home Secretary, talking about Britain’s contribution to Europol: “If we left, we would take our information with us.”

And this is Alex Younger, the head of MI6, in his first public speech three months ago addressing the issue of Brexit and security: “The need for the deepest cooperation can only grow. And I am determined that MI6 remains a ready and highly effective partner, just as the UK is and will be. These partnerships save lives in all our countries.”

Whose views should the people of this country, a week after the Westminster attack, believe offers greater protection against terrorism? The chief of the intelligence service? Or politicians trying to use public safety as a bargaining tool?

The position of May’s Government on this issue is risible. How, one may ask, will it actually translate into reality? Does it mean that the intelligence and security services of this country will be ordered not to pass on evidence to the French on another atrocity being planned in Paris? Or refuse to accept warnings from EU states about another attack on London? Or decline information on the remaining hundreds of British jihadists heading back across Europe from Syria, after Isis is defeated later this year?

The European Parliament’s Brexit coordinator, Guy Verhofstadt, is quite right to accuse May of attempted blackmail with her threat. And the former Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, Sir Nicholas Macpherson, is also right to say that it is “not a credible threat to link cooperation to a trade deal”.

The fact is that terror is transnational, as Younger and his colleagues have repeatedly pointed out, with jihadists plotting with and being inspired by each other across borders. The Italian police announced today that they had foiled a plan to blow up the Rialto Bridge in Venice. The alleged plotters, Kosovar Muslims, were recorded celebrating last week’s London attack.

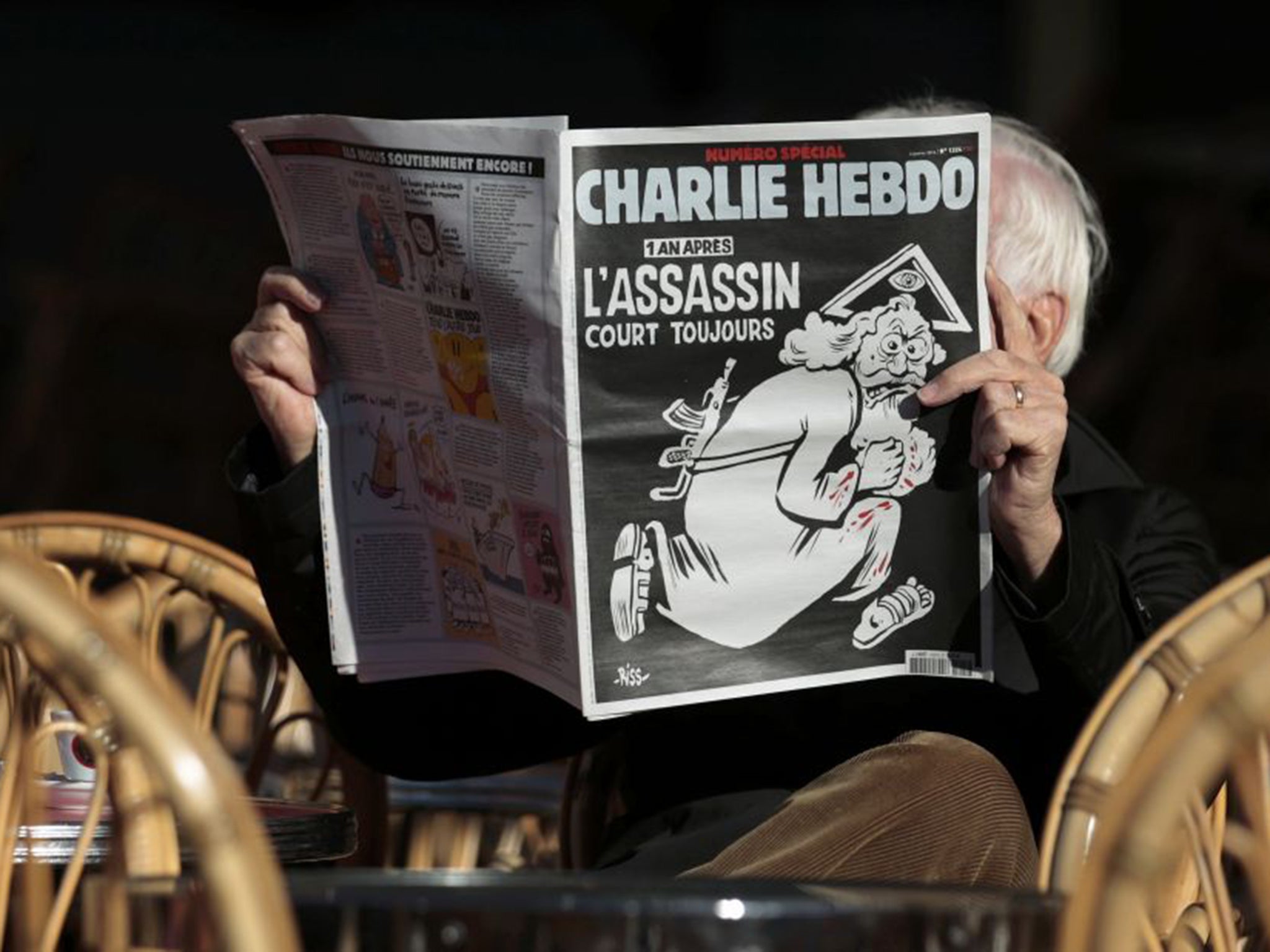

The failed 21/7 London bomber, Hussain Osman, was arrested in Italy after fleeing there and sent back to the UK. Three months ago, Zakaria Boufassil, from Birmingham, was convicted of funding international terrorism at Kingston Crown Court. He had given £3,000 to Mohamed Abrini, accused of taking part in the Brussels airport bombing last March. Djamel Beghal, an al-Qaeda recruiter, was the mentor of Cherif Kouachi, one of the gunmen who carried out the Charlie Hebdo murders in Paris was a worshipper in the past at the Finsbury Park mosque and followers of two British based extremist clerics, Abu Qatada and Abu Hamza. Three boys from St Joseph’s school in Brittany, in London on a visit, were seriously injured when the British Muslim convert Khalid Masood ploughed into a crowd last Wednesday. A former pupil from the same school was murdered during the Bataclan attack in Paris.

Britain is a major source of intelligence for security agencies in the European Union. GCHQ, which works in close partnership with America’s National Security Agency, is a prime supplier of this. The UK is also a substantial contributor of information to the European police agency, Europol. But the traffic is certainly not just one way. Terror attacks have been stopped in this country due to intelligence from foreign services, in Europe and beyond. And as Rob Wainwright, the British head of Europol, points out, law and order in the UK has been hugely aided by the use of the European Arrest Warrant – a tool which Britain will no longer be able to use if May’s Government follows through with its threat of pulling out of Europol.

Essentially, the arrest warrant has stopped a large number of foreign criminals from walking the streets of Britain. Between 2010 and 2014, the UK sent 5,365 suspects to other European Union countries. Among them were 115 wanted for murder, 100 for rape, 70 for child trafficking offences and 479 for drug trafficking. At the same time, around 700 were sent from the European Union to Britain. Of these,189 were handed over by Spain, effectively drawing to an end the “Costa del Crime” as a haven for bank robbers and drug traffickers from the UK. The Association of Chief Police Officers of England and Wales, unsurprisingly, called the warrant an “essential weapon”.

There was a period in the past when Britain thought it could deal with Islamist terrorism at the expense of its European partners – with devastating consequences. For years violent Islamist groups were allowed to settle in Britain, using this country as a base to carry out attacks abroad, including in France. This was tolerated in the belief that they would not bomb the country where they lived, and that the security service would be able to infiltrate them. At the same time, mosque after mosque was taken over through intimidation by fundamentalists. The police and the Home Office refused pleas from moderate Muslims for help with the excuse that they did not want to interfere in community matters.

There was even a name for this amoral accommodation – the “covenant of security”. We now know, of course – to great cost – that jihadists will blow up their places of refuge. We also know that infiltration in an attempt to stop this happening did not work.

The vital need for international cooperation against terrorism and crime is a lesson which has been hard learned. It is an example of this Government’s shallowness and increasing desperation over Brexit that this crucial issue has even been mentioned as a bargaining chip in negotiations.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments