I’m applying for German renationalisation. Like other British Jews, Brexit has put my safety in danger

We won’t even be close to becoming German by 29 March, but what’s driving me is the same reason my family became British in the 1930s: survival

It was during the 2016 referendum campaign that my family first realised we could restore our German citizenship, thus retaining our freedom of movement in Europe. The application seemed a bit of a faff, and not many people knew of our family’s refugee history. Adopting a new nationality had seemed ridiculous; we didn’t speak German, hadn’t lived in Germany for generations, and our family had fled in terror from the Nazis.

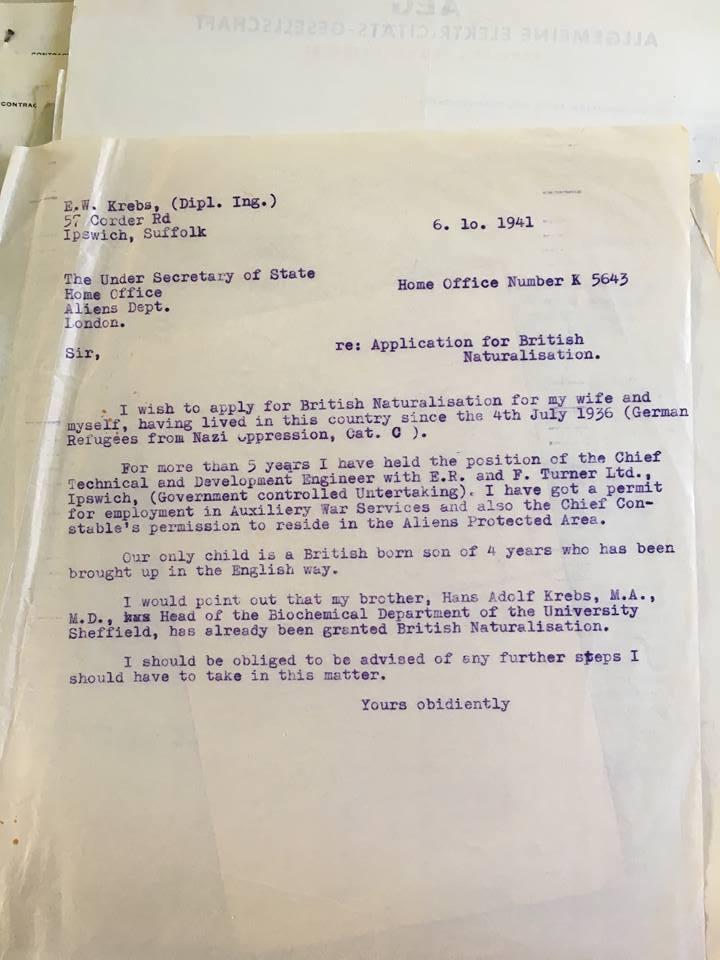

Fleeing to the UK in 1936, my great-grandparents Wolfgang and Lotte Krebs and their young son Peter were stateless for over a decade. First applying for British nationalisation in 1941 they were denied citizenship for 11 years, instead relying on short-term promises by the government and their employer to be able to stay living in Ipswich, where Wolf was an electrical engineer.

White privilege and the model minority trope meant Wolf and Lotte could more easily assimilate to British culture than refugees and migrant people of colour. Lotte would tell friends that she picked up her Germanic accent whilst travelling the continent. Both Lotte and Wolf, who practised liberal Judaism in Germany, became secular on British soil.

They benefited from being highly educated, Wolf being released from internment on the Isle of Man after the British government realised his qualifications in electrical engineering could help the war effort. In a letter to the Home Office begging for British naturalisation, Wolf assured the authorities that his son was “brought up in the English way”.

Being able to conceal their identity in order to survive in a xenophobic antisemitic post-war Britain could not erase the reality of their history and personal trauma. Wolf and Lotte were careful to never plant roots too deep – keeping a packed suitcase underneath their British bed for 40 years – ready to once again flee at a moment’s notice.

In applying to be German, then, I feel somewhat conflicted. German was a citizenship that was legally stripped from my family by the Nazis in 1935, and an identity that, until now, no one in my immediate family has wilfully reclaimed. While I am still also retaining British nationality, identifying as German is an identity that requires relearning, serious self-reflection and is ultimately driven by the same reasons my family became British in the 1930s: survival.

The year of the EU referendum campaign saw a sharp rise of incidents of antisemitic hate than the previous year. Being a member of the EU was a metaphorical suitcase stashed under the bed. Never truly putting down roots was an inherited behaviour, being watchful and cautious; Wolf and Lotte’s son Peter moved a total of 15 times in his adult life until his death earlier this year. With no out, Brexit has driven over three thousand descendants of Jewish refugees to apply for German citizenship.

Trying to find the paperwork needed for the Restoration of German citizenship (Article 116 II Basic Law) was deeply emotional. My family’s birth and marriage certificates were scattered through yellowed family photographs, German telegrams and personal letters. My mum and I found Wolf’s Certificate of Registration, a booklet of stamps telling him which restricted areas he could travel to as an “alien”, and detailing his internment on the Isle of Man in 1940.

Mum found Lotte’s certificate awarding her bicycle privileges. Wolf’s brother, Hans Krebs, received British nationalisation and went on to win the Nobel Prize in 1953 for his work on biochemistry based in Sheffield. It was a collage of refugee life. The folders filled with family history weren’t disorganised so much as proving that love necessitated survival. They knew their remaining family in Germany were being murdered, and so the desperation of Wolf’s letters to the Home Office shines through every paragraph, ending, always, pleading “yours obediently”.

Photographs of Lotte with her sister, Trude Rittmann, seemed completely chipper until finding a letter from 1943 outlining how lonely and desolate Trude and her mother were as refugees in New York. Trude, despite the adversity and trauma faced as a refugee, eventually became a Broadway composer.

Sourcing important 80-year-old documents in a language I hadn’t studied since I was 13 was quite a shaky task. We found a kind solicitor to help us, only to be told by the German embassy after sending the documents that they had to be certified by embassy officials. The application process, however, was relatively straightforward and completely free; a luxury my great-grandparents certainly never received.

We’re awaiting my grandparents’ marriage certificate before we can take all the documents to be certified to the German embassy. The process is far from over, and we won’t even be close to becoming German by 29 March. Having a chance to remain a European citizen is a privilege few British people have.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments