When it comes to former PMs, some reinvent themselves better than others

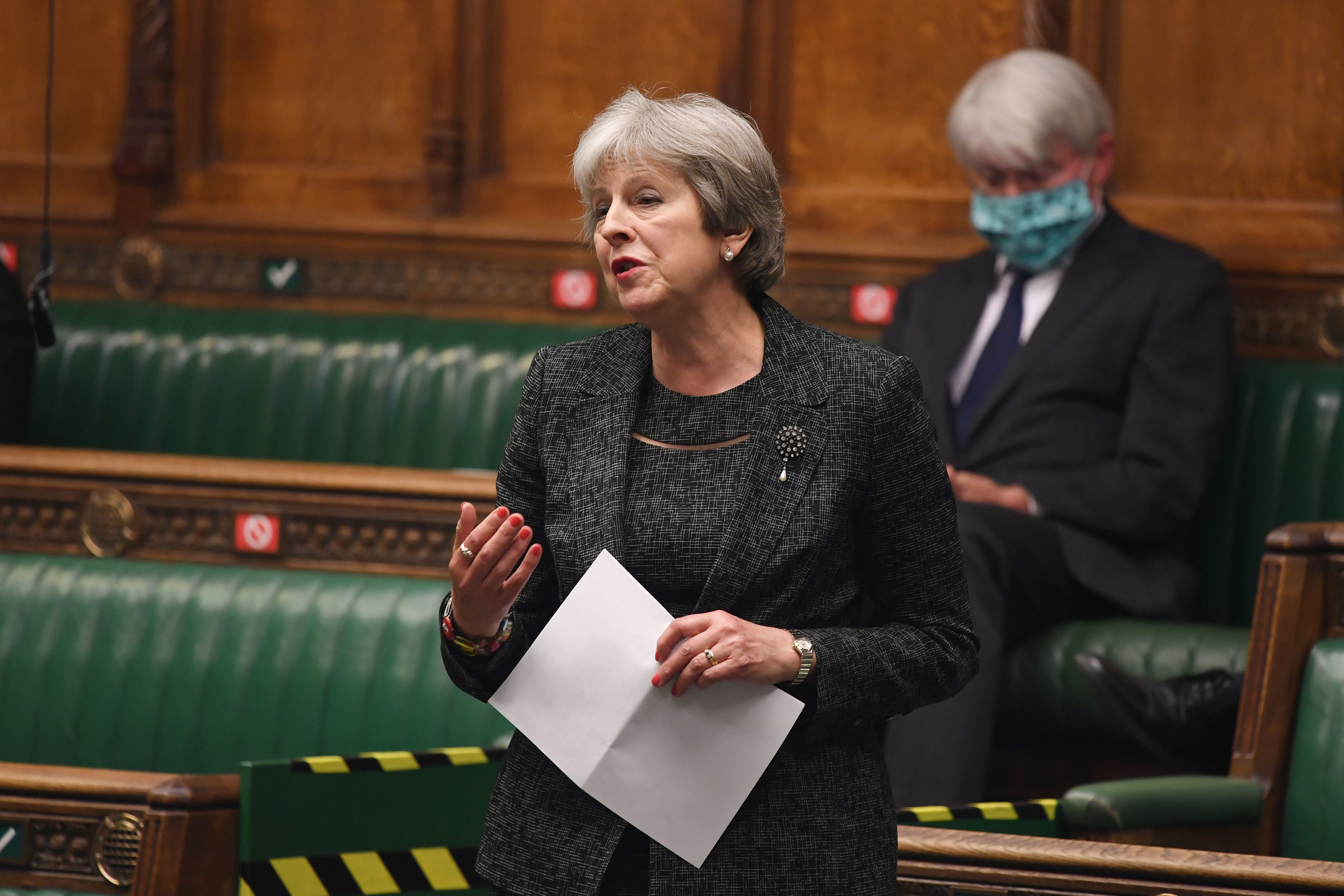

Incapable of greatness as a prime minister, Theresa May is nevertheless making a mark on the back benches – but what does the future hold for Boris Johnson?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I just rewatched the most excruciating moments of Theresa May’s 2017 Conservative Party conference speech. You know, the one where the letters fall off the wall, and she coughs her way through the key applause lines and gamely ad-libs as she’s passed a P45 by a prankster dressed as a Tory boy.

I also rewatched the embarrassing jive she performed a year later as she bounced on stage to the strains of “Dancing Queen”. And finally, for good measure, her tearful farewell in May 2019 as she announced she was leaving Downing Street, unable to persuade her MPs to back her Brexit withdrawal deal.

In a premiership lasting a little under three years, the world watched May’s painful political death many times over. Humiliated and lonely, she seemed destined only to enter the history books for what she failed to achieve.

And yet she’s been reborn. Incapable of greatness as a prime minister, she is nevertheless making a mark on the back benches.

Yesterday, May got to her feet in Prime Minister’s Questions to speak up for the victims of the Hillsborough disaster, who have spent decades trying and failing to get justice.

This was just the latest in a series of well-chosen interventions by the former premier. Earlier this week, May joined Conservative rebels on the argument over international aid, admonishing her successor for his decision to (temporarily) ditch his manifesto commitment, which she said “will have a devastating impact on the poorest in the world and damage the UK”.

In March, after the death of Sarah Everard, she neatly expressed fears about the government’s policing bill, saying: “I would urge the government to consider carefully the need to walk a fine line between being popular and populist.”

And last year, on the subject which cost her her job as prime minister, she made an observation as sharp as one of her favourite kitten heels. After the government had shown itself willing to break international law over the Brexit agreement, she warned that such a move would do “untold damage to the United Kingdom’s reputation”.

When she speaks, people from across the Commons now listen. No small feat for a woman who had been reduced to a meme by the time she left office.

Perhaps her predecessor David Cameron could learn a thing or two from her. He segued straight from the ignominy of losing the Brexit referendum to publishing his memoirs, before being plunged into scandal via his involvement in the Greensill affair. He’s going to have to work very hard as president of Alzheimer’s Research UK to rehabilitate himself.

May, by contrast, has already made great strides to escape the shadow of her time in Downing Street.

It’s an achievement she shares with two other former prime ministers, Gordon Brown and Sir John Major. Both, like her, were mocked and derided when they held the top job. Both have now earned a measure of respect from their political peers – and, though it’s hard to judge, from the public too.

All three have chosen their interventions carefully. Brown has written books, and opined on weighty issues such as saving the Union, educating the world and ending child poverty.

Sir John, meanwhile – who, like May, met his end over Europe – has made impassioned contributions on Brexit and, most recently, on foreign aid. He also proved a thorn in Tony Blair’s side over the Iraq war.

Which brings me to Blair himself. After quitting No 10 and writing a bestselling memoir, he was continually haunted by Iraq. Sir John Chilcot’s devastating inquiry brought forth no contrition from Blair, and for his detractors, the years haven’t softened the sense of anger. Indeed, his decision to advise countries with poor human rights records – giving image advice to the ruler of Kazakhstan a decade ago, for example – merely confirmed his critics’ dim view of his moral compass.

And yet, even he now gets a respectful hearing. On the future of Britain and Europe, the future of the Labour Party, the future of the world post-Covid: Blair and the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change have much to say.

In fact, returning to Theresa May, her thoughtful Commons contributions have surely demonstrated that she has rather more to say than we all thought. Where Blair, Sir John and Brown use the media judiciously, May – never a fan of the big broadcast interview – has so far steered clear. This is a shame; as important as parliament undoubtedly is to May, she could use a more prominent platform. What better way to demonstrate that not all political careers end in failure?

As for the incumbent, Boris Johnson, the pressures of the present – the pandemic, and Britain’s uncertain role in Europe and the world – will determine whether he too can defy the old adage while in office, or if he will have to forge a new role beyond it.

Cathy Newman presents Channel 4 News, weekdays at 7pm

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments