You win the Booker - and splash your cash on a tracker mortgage… what’s the story?

Paul Lynch, the author of Prophet Song, raised a few eyebrows when he said he’d use his winnings to put towards paying off his house. It’s a sign of hard times, writes Richard Godwin – and a far cry from the days when writers blew it all on swimming pools and other perfectly useless extravaganzas

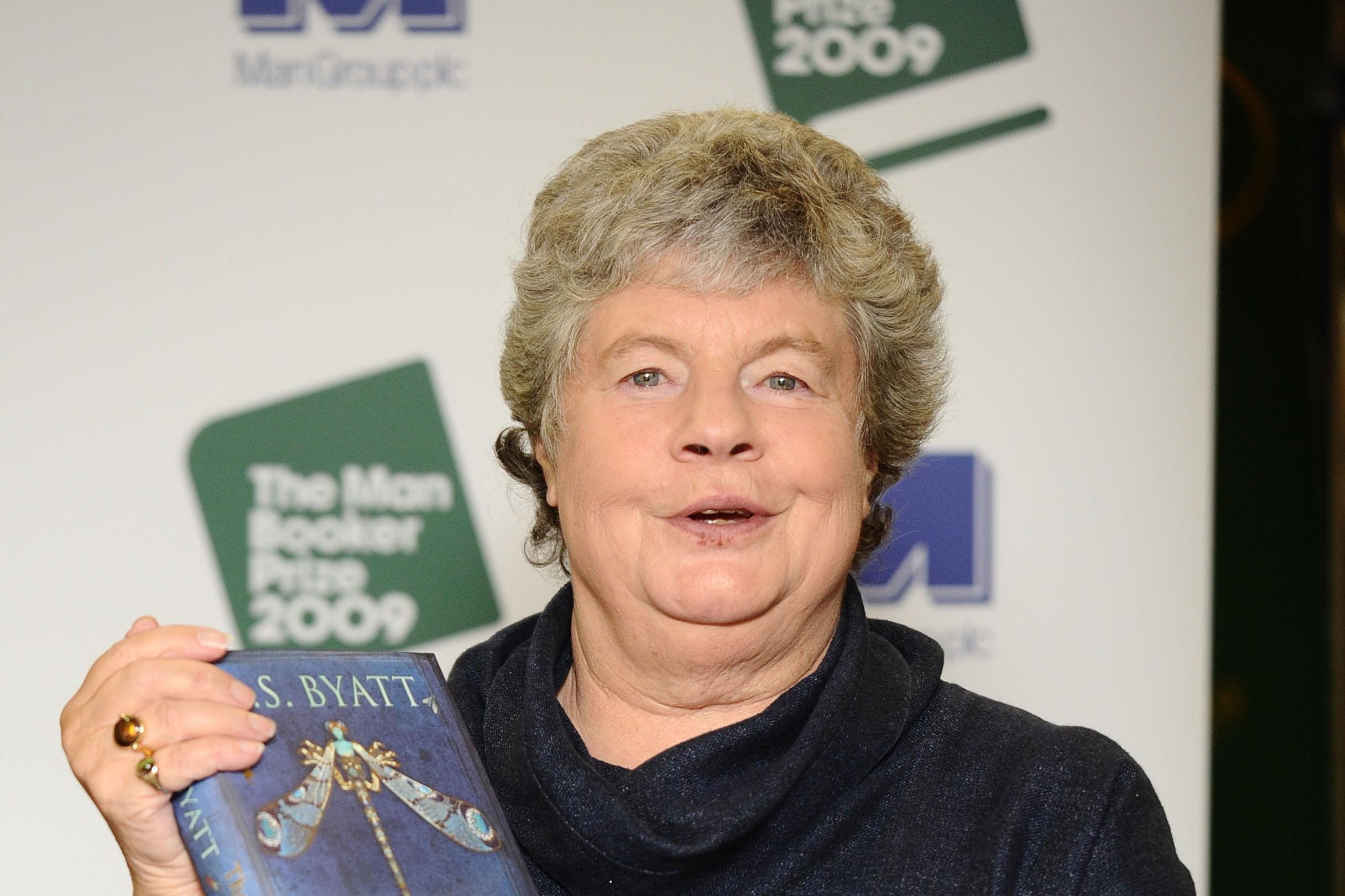

When the late AS Byatt won the Booker Prize for Possession in 1990, she famously promised to spend the prize money on a swimming pool for her house in Provence. In 2009, Hilary Mantel vowed to blow her Wolf Hall bounty on “sex, drugs and rock’n’roll.” The 2015 winner, Marlon James, looked forward to buying the Ozwald Boateng suit he’d always craved.

So it was a little disconcerting – and slightly depressing – to learn how prosaically the Irish author Paul Lynch intends to spend the £50,000 that his novel, Prophet Song, has earned him.

At the Booker Prize ceremony in London last night, the chair of the judges, Esi Edugyan, said that his book “speaks to the immediate moment while also possessing the possibility of outlasting it”. The same surely applies to Lynch’s intention to use his jackpot to make a dent in his tracker mortgage. Yes, what the modern artist craves is not champagne or diamonds but a reduction of their monthly direct debit payment. Inflation being what it is. And the times being what they are.

So no, it’s not quite John Berger, in 1972, promising to give half of his winnings for G. to the British Black Panthers. Or even Ian McEwan in 1998, announcing that he’d probably spend the cash on “something perfectly useless”. I can’t help feeling it’s a bit damning of the wider literary culture that a writer’s first thought is not “champagne all round!” or some subversive cause but ooh, I must get on the blower to Santander. What chance does great literature have in such conditions?

Of course, it may well be that Lynch dreams up some more creative outlet for his cash in the coming days. To be fair, he was put on the spot. And it is a rude question. Albeit a predictable one. He had taken the time to prepare a fulsome acceptance speech, in which he quoted Albert Camus and the “apocryphal gospels”, and thanked the children of the world for their “innocence” – so he might have put some thought into the £50,000.

And while spending the lot on, say, a private jet to Antarctica might have been in poor taste given his subject matter, there was always the option of a money-where-your-mouth-is gesture. When Katherine Rundell won the non-fiction Baillie Gifford Prize for Super-Infinite in 2022, for example, she pledged to split her £50,000 prize money between refugee and climate charities. Berger gave his money to the Black Panthers as part of a protest against the Booker group’s historical exploitation of the Caribbean.

Then again, material circumstances differ. Berger worked at a time when housing wasn’t nearly so expensive – and he also made a point of using the other half of his winnings in order to fund future work. “I badly need more money for my project about the migrant workers of Europe,” he announced in his speech. “The Black Panther Movement badly needs more money for their newspaper and for their other activities. But the sharing of the prize signifies that our aims are the same. And by that recognition, a great deal is clarified. And in the end – as well as in the beginning – clarity is more important than money.” No doubt.

Meanwhile, Lynch’s concern about his mortgage reveals a blunter truth about art: that however much we romanticise writers – however much we hold them to high moral standards – they, like anyone else, need a measure of material security and even comfort if they are to produce their best work. Or any work at all.

Lynch acknowledged as much with his praise of the Irish Arts Council, whose generous per capita funding (approximately five times that of the UK) goes some way to explaining the great mystery of why Irish writers are so dominant. His fellow Irish shortlisted author Paul Murray took 10 years over his book, The Bee Sting (which he wrote longhand by the way) and I doubt he supported his family on vibes alone during that time.

Byatt herself later said that her swimming pool kept her “alive and mobile” and who knows? Maybe we’d have had a couple of fewer novels without that pool. Mantel admitted that what her prize money really did was to buy her time to work on her Wolf Hall sequels and stage adaptations. Anna Burns, winner in 2018 for Milkman, said she would use her money to “clear her debts”. Could we correlate a perceived decline in literary standards with an increased precarity in authorial living arrangements? How many of the great works in the canon have been produced by writers who didn’t have to worry about their mortgage?

The point is, all any writer wants, really, is the means and the space to write. Virginia Woolf wrote a famous essay about that once: “I hope that you will possess yourselves of money enough to travel and to idle, to contemplate the future or the past of the world, to dream over books and loiter at street corners and let the line of thought dip deep into the stream,” she wrote to a generation of would-be female writers in A Room of One’s Own. The point is: without financial independence, it’s almost impossible for anyone to write anything. Whether it’s any good or not is another matter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments