The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

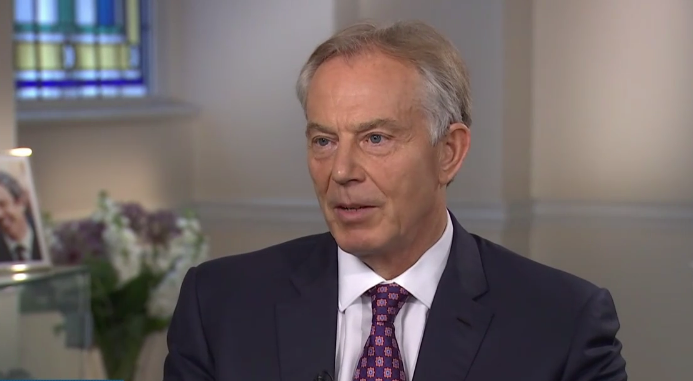

Blair is entitled to defend himself when Corbyn calls him a war criminal

The former Prime Minister said that his successor as Labour leader was ‘the guy with the placard’, engaging in the politics of protest not the politics of power

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Tony Blair is entitled to defend himself when he is accused of being a war criminal. He is entitled to point out that he was Prime Minister when Britain, a democracy, helped to fight actual war criminals in Kosovo, Sierra Leone and Iraq. So when his successor as Labour leader indulges in offensive name-calling, he is within his rights to say what he thinks.

Naturally, this has prompted yet another round of indignation that he should be trying to “pre-empt” the Chilcot report, something something “spin”, as if defending himself when insulted is going to soften up public opinion and make journalists report Chilcot’s findings in a way that is more favourable to him.

The facts are that he feels an obligation to take part in the national debate about Europe, and every time he does so he is asked about Iraq. Yesterday he was interviewed by John Micklethwait, editor-in-chief of Bloomberg News, and he was asked, on the 13th page of a 17-page transcript, about Jeremy Corbyn suggesting he might be tried for war crimes.

In the circumstances, I thought his response was mild:

I’m accused of being a war criminal for removing Saddam Hussein, who by the way was a war criminal, and yet Jeremy is seen as a progressive icon as we stand by and watch the people of Syria barrel bombed, beaten, and starved into submission and do nothing.

It is worth remembering, and Ann Clwyd reminded us at Prime Minister’s Questions yesterday, that Blair did not act alone on Iraq. The Cabinet and the House of Commons approved the decision to join the military action (and it was only under Blair that such things were put to a vote of MPs), and if Corbyn accuses people of being responsible for war crimes he is accusing eight members of his own shadow cabinet who voted for military action, and altogether about 50 of his MPs.

Perhaps he, and all those preparing to denounce Blair regardless of what Chilcot says, should prepare themselves by reminding themselves what actually happened in 2001-03, as opposed to the myth pickled in rage.

Steve Richards has just published a very good, short e-book, Blair & Iraq, which costs just £1.99 and explains how a cautious, big-tent politician found himself trapped into taking a big political risk and losing half his party.

Richards makes the important point that Blair did not lie about Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction. “Would Blair lie overtly about WMD when he knew he would be found out once the conflict had ended?”

I disagree with Richards about why Blair presented patchy intelligence as more certain than it was. He says that Blair wanted to expunge Labour's past image as weak on defence, to deny the Conservatives space on national security, to be a strong ally of the US and to retain the support of Rupert Murdoch. All those are true, but two other points are important. Because of Saddam's obstruction and past deceptions, most intelligence services were convinced Saddam was hiding something. That groupthink gripped all American and British officials and politicians. Blair himself had long believed that Saddam was a threat, and even before 9/11 advocated military action to force him to comply with UN disarmament resolutions.

Richards implies the WMD case was a contrivance, because it was the best way to persuade sceptical public opinion and lawyers to support what he wanted to do for other reasons. I think that is mistaken. The spies and politicians were certain Saddam had WMD, and that certainty was part of a larger conviction that he was a menace who had to be confronted, by force if necessary.

It is also worth listening to Professor Vernon Bogdanor’s lecture at Gresham College last month on the Iraq war. It is a clear, factual and traditional-history account of the period, with less of the political context that Richards brings. But it, too, is an important antidote to the version espoused by Corbyn, which starts from disagreeing with the invasion, assumes Blair deceived the nation and builds a vast conspiracy in hindsight from there.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments