Biographers: Why do they fall out with the family and friends of their subjects?

There are worse things to get enflamed about, surely, than poets’ lives and the idea of objective truth

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The flamboyant Conservative MP Alan Clark (1928-99) made his pre-parliamentary reputation as a historian, most notably with The Donkeys (1964) a pungent critique of the military establishment during the First World War.

The flames of controversy were further stirred when Clark received a letter from the family of the late Field Marshal Haig complaining about a passage which described the future commander of the British Expeditionary Force in Flanders, pictured on the morning in 1915 when he strode out to greet his sovereign King George V, as “pink-cheeked and well-breakfasted”. Happily Clark was able to write back itemising the considerable meal which Haig had put away before the royal visit, revealing that the temperature was just above zero and confirming that the subject was known for his excellent digestion. Pink-cheeked and well-breakfasted he indisputably was.

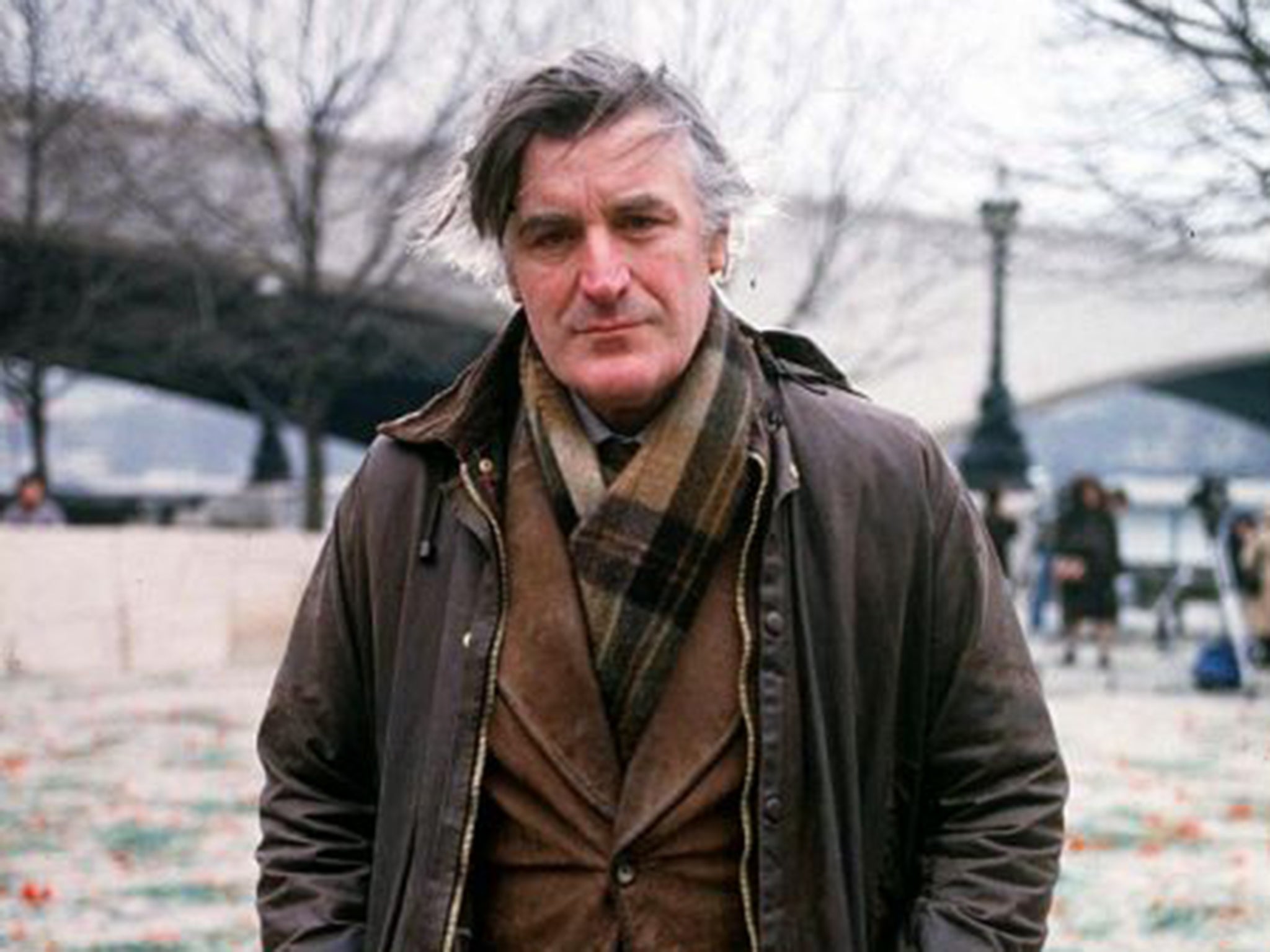

I recalled this episode the other day, while reading the reviews of Professor Jonathan Bate’s Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life. Very good reviews they were, for Professor Bate’s scholarly reputation is second to none, and the book has just been shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize. There was also praise for an accompanying TV programme, fronted by the biographer, about the life and times of Hughes. Only one vital element seemed to be missing from this gush of interest, I told myself, and that was the letter of protest from a member of Hughes’s family or his childhood friend lamenting that the writer had done them wrong, that trust had been abused, and what had set out as an objective study of temperament and genius had ended up as a hatchet job.

There was no need to worry, for Hughes’s widow, Carol, and his estate lawyer, Damon Parker, turned out to have Professor Bate firmly in their sights. A letter sent to the proud author and his publishers, Messrs HarperCollins, claimed to have identified 18 factual errors or unsupported assertions in a bare 16 pages. Among the mistakes which caused particular offence was a statement that as the Poet Laureate’s body was being returned from London, where he died, to his home in Devon, the party stopped “as Ted the gastronome would have wanted, for a good lunch on the way”, and a description of the scenes at Hughes’s deathbed which only mentioned his two children, giving the “false impression” that his wife was absent. In fact Mrs Hughes had slept in her husband’s hospital room for the last two nights of his life.

There is, inevitably, a back-story to all of this, which is that Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life began as an authorised biography, only for the biographer, as so very often happens in these circumstances, to fall out with his sponsors who henceforth ceased to co-operate with him. Speculation is, of course, profitless, but it is thought that the withdrawal of that absolutely vital gift, permission to quote from unpublished work, may have had something to do with Professor Bate’s interest in the poet’s incendiary private life. Predictably, the letter sent back by HarperCollins to the Hughes estate notes that attempts to corroborate certain points were made more difficult by the breakdown in this relationship.

A careless biographer or an over-sensitive relict? Working out where you stand in a case like this is never easy. Professional solidarity, and practical experience, incline me towards Professor Bate: no book of nearly 600 pages is ever going to be flawless, and even the most assiduous researcher sometimes gets things wrong. I was mortified once to get a letter from the widow of a man called Hugh Slater politely pointing out that he and a certain “Humphrey Slater” also at large in a book I had written were the same person. On the other hand, the bit in Professor Bate’s book – also strenuously denied – about the family home being shut up after the funeral, with its hint that the mourners were denied hospitality, pointed me momentarily back in the direction of Mrs Hughes, even if this massaging of the facts is nowhere near as bad as, say, Kingsley Amis’s biographer Eric Jacobs offering readers of The Sunday Times a loaded account of his subject’s funeral – an event Jacobs had not actually attended.

It is a mark of the importance that still attaches itself to biography as an art form that practically every example of it that appears in a publisher’s catalogue tends to cause offence to someone. Among recent great lives, for example, Lord Ashcroft’s attempt on David Cameron has been criticised for score-settling and the substitution of tittle-tattle for established fact. Everything She Wants, the second volume of Charles Moore’s life of Mrs Thatcher, whose 200th page I reached shortly before beginning this article, has been twitted for its partiality. From the author’s point of view these, it goes without saying, are proud scars. In fact, memory insists that half the biographies staring at me from the study shelf as I write, from Andrew Motion on Larkin, to Nicholas Shakespeare’s on Bruce Chatwin and Claire Tomalin on Dickens – a man dead these 144 years – had some friend, relative or scholarly partisan crying foul.

All this raises the associated questions: who is the biographer writing for, and to whom is he or she ultimately responsible? If the answer to the first question hangs tantalisingly out of reach, the second’s answer is “the subject”. The difficulty here is that life-writers who believe that their sole duty is to the person they happen to be writing about are almost guaranteed to upset the keeper of the flame. Sonia Orwell, for example, went to her death in 1980 convinced that she had betrayed her husband’s memory by allowing Bernard Crick to write his first, pioneering biography Orwell: A Life. Posterity, alternatively, would probably maintain that Crick’s view of Orwell was just as valid as Sonia’s, even if Crick lacked the substantial advantage of being married to him.

And if the biographer’s duty is to the subject, then what kind of procedural tools should be brought to the job? Most writers – and, in a prurient age, most readers – would probably vote for maximum disclosure, but it might be argued there are some subjects where, mysteriously, maximum disclosure works less effectively than tact and stealth. Andrew Motion, for example, once spoke feelingly about the approach he took to those of Larkin’s girlfriends who, in his biography, exist in relative shadow beyond the firelight of his long-term relationship with Monica Jones: ordinary people, Motion deposed, who just happened to have moved in the orbit of a famous poet and who, in return for the help they offered, should be given the courtesy of not having their knicker drawers – real or metaphorical – turned out.

The advantages of this kind of subtlety are also apparent in Everything She Wants. Here the reader will intermittently stumble on fascinating incidents in which Mrs T loses her rag or makes some incriminating remark, look up the reference and find only the words “private information” when it would have been even more fascinating to know the informant’s identity. Moore’s defence of these smokescreens would doubtless be that the supply of data rested on anonymity; better a masked donor than nothing at all.

Meanwhile, the row between Professor Bate and Hughes’s family and lawyers grinds on. It will never be resolved, these things never are. All one can predict is that eventually an “authorised” life will emerge, licensed by the estate and offering a rather different story. That large numbers of people are so concerned by what may or may not have happened on the road to Devon in October 1998 is undoubtedly a good sign: there are worse things to get enflamed about, surely, than poets’ lives and the idea of objective truth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments