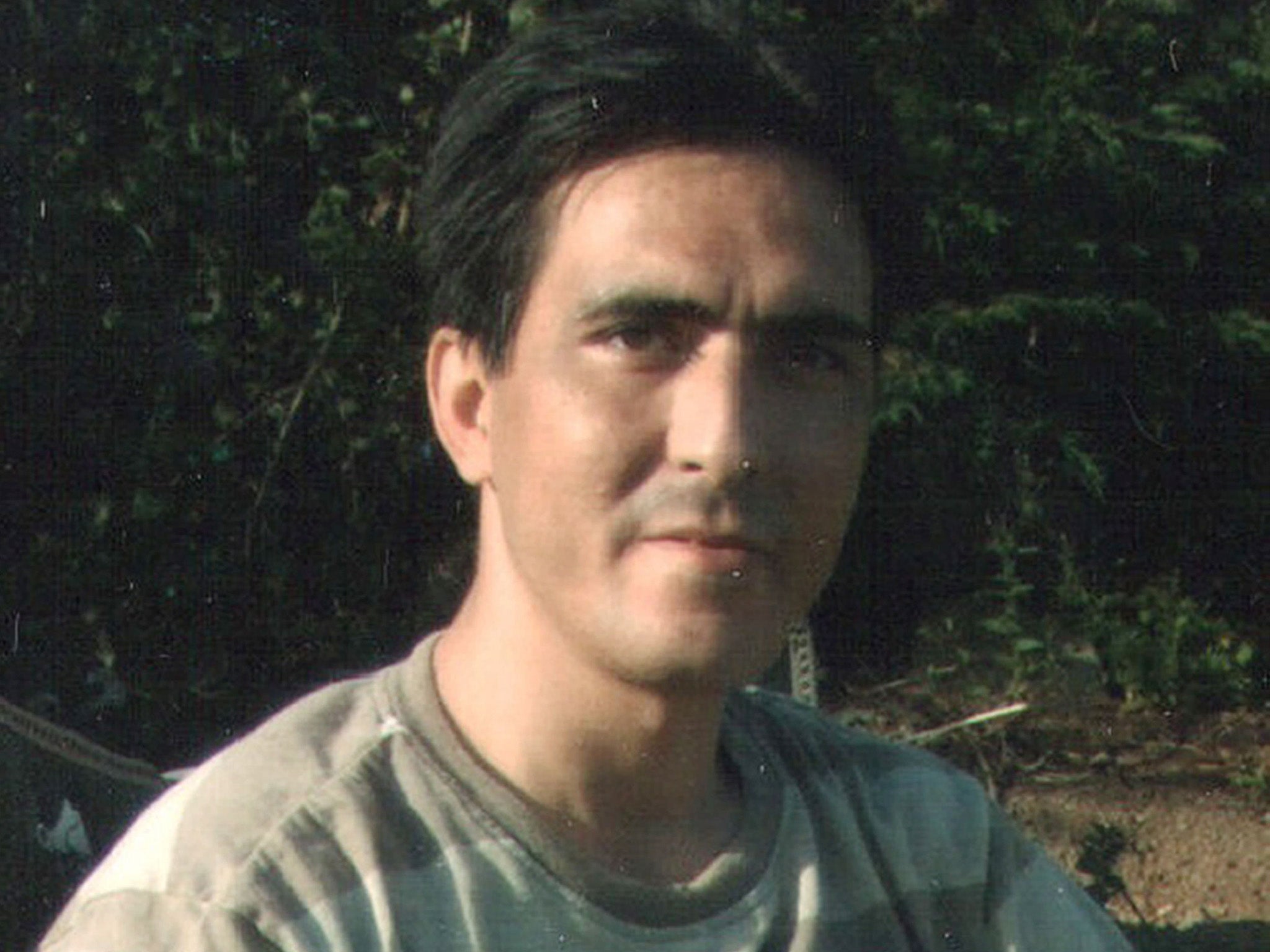

The tragic case of Bijan Ebrahimi means BME people need to seriously consider entering the police force

In 73 of 85 telephone calls that Ebrahimi made to the police between 2007 and 10 July 2013, he reported racial abuse, criminal damage and threats to kill. Despite this, the police failed to record a crime on at least 40 of those occasions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Following the IPCC investigation into poor responses to a disabled Iranian refugee, Bijan Ebrahimi, Avon and Somerset Constabulary were found guilty of “institutionalised racism”. Ebrahimi was victimised for at least seven years and subsequently murdered horrifically by his neighbour, Lee James.

In 73 of 85 telephone calls that Ebrahimi made to the police between 2007 and 10 July 2013, he reported racial abuse, criminal damage and threats to kill. Despite this, the police failed to record a crime on at least 40 of those occasions. Moreover, it was Ebrahimi who was accused of being a liar, a nuisance and an attention seeker. In addition, the Constabulary failed to challenge unsubstantiated rumours that Ebrahimi was a paedophile. They allegedly sided with his abusers, took his neighbours’ counter allegations at face value and treated him differently to his neighbours without explanation.

In April 1993, an 18-year-old black British man, Stephen Lawrence, was stabbed to death in an unprovoked attack by a gang of white youths. Initially, five suspects were arrested, but not convicted. It was alleged that the attack was racially motivated and that the police handling of the case was affected by issues of race.

The Macpherson report on the Stephen Lawrence case, published in February 1999, showed that a number of officers who used terms such as “coloured” or “negro” did not seem to understand that those terms were offensive. Lord Scarman accepted that some police officers were guilty of "ill considered, immature and racially prejudiced actions...in their dealings on the streets with young black people".

These tragic cases pose the question as to whether more people from BME backgrounds should join the police force. Currently, most UK police forces have a disproportionate number of white officers. According to a House of Commons’ Policy Diversity report, no police force in England and Wales has a BME representation that matches its local demographic.

In a 2016 study by Mawby, R and Zempi, I (2016), qualitative interviews with 20 police officers uncovered their experiences of bias, prejudice and hate internally. BME officers described “double standards” in areas such as probation, training, deployment and progression.

In 1999 the then-Home Secretary, Jack Straw, set targets for police forces in England and Wales to recruit black and Asian officers. Each force was handed a quota to meet within 10 years, a reform that was prompted by police handling of the Stephen Lawrence murder. Nevertheless, in 2009, the central targets were dropped to allow forces to determine their own recruitment policies.

So why are police forces failing in their BME recruitment efforts and what can be done to improve the situation? Are their recruitment personnel guilty of unconscious bias i.e. making assumptions and associations about people’s characteristics based on their ethnicity, gender or sexual orientation, or are they generally prejudiced?

A Home Office report, Attitudes of People from Minority Ethnic Communities towards a Career in the Police Service, showed that potential candidates were discouraged by the thought of having to work in a racist environment and having to face prejudice from colleagues and the general public on a daily basis. Others believed that racism had been a deciding factor in their unsuccessful applications and that the police did not understand those from different cultures. A recurring theme was that racism in the police would need to be tackled before they would consider joining the police force.

In support of its BME Progression 2018 programme, the College of Policing commissioned a review of the research literature to identify interventions that might reduce unconscious bias in organisations’ recruitment, retention and progression processes. Another of its programme objectives is to support forces in improving recruitment, retention and progression of BME officers through the provision of advice, information and stakeholder events.

The police force needs to demonstrate that with the right skills, determination and commitment to the law, you can be a police officer, regardless of your ethnicity or background.

Diversity within the police force is essential. Not only will it make diverse communities feel represented, but BME officers may have the cultural awareness and language skills to interact effectively with hard-to-reach communities.

As a councillor, I encourage my constituents to work with the police so that we can make our neighbourhoods safer. I was the first councillor in Tower Hamlets to encourage residents to work with the police and local council departments in a Lethal Weapon search in Shadwell as part of a crackdown on knives and possible weapons. Let us also not forget the role the police have played in the recent terrorism events, along with all our emergency services. What it has taught me is that the police and residents must have a community policing partnership so that we have strong aspiring communities and not just safer neighbourhoods.

Yes, there are deep rooted and embedded prejudice and bias problems within the police force, but as a Muslim woman I would still encourage people from BME communities to consider joining the police force, because by participating we can bring change. Before I became a councillor, I worked on a project with the police to dispel the myths and stereotypes surrounding Muslim women.

Sir Robert Peel’s Principles of Law Enforcement 1829 stated that the police at all times should maintain a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and the public are the police. Therefore, for the public to have trust and confidence in the police, the force must understand and reflect the communities they serve.

Minority communities must not give way to the ignorant few in the police and no matter how devastating these events are, they must not deter us from joining. Such events need to be accountable to us, the public and law makers but minority communities must remember that they are an integral part of British society; we can be part of the police force and we can effect change.

Throughout my life I have learnt that we can learn from our mistakes, but giving up is never an option.

Rabina Khan is a writer and politician who is currently a councillor in Tower Hamlets, east London

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments