The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

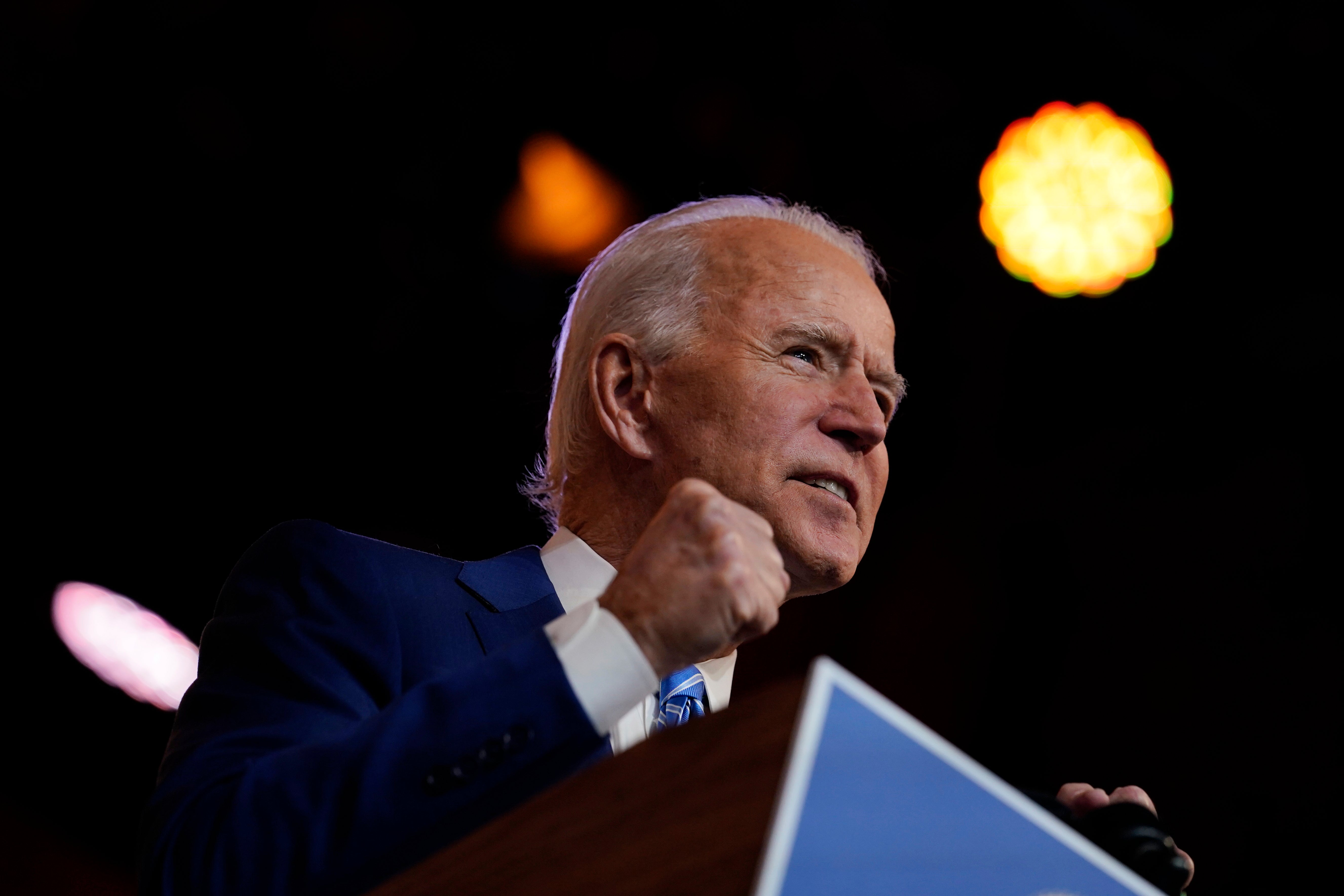

What Biden should actually say in his inauguration speech

There are a few historical moments which the President-elect should take his inspiration from in January

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Biden’s inaugural address presents an opportunity not only to calm a combustible nation but also to set the terms and define the stakes of his leadership for the next four years. There are four presidential transitions and resulting inaugural addresses that he should bear in mind while preparing his own: Ford-Carter, Eisenhower-Kennedy, Hoover-Roosevelt, and Johnson-Grant.

Numerous analogies have been drawn between the disgraced and impeached Andrew Johnson and Donald Trump, specifically their inflammatory rhetoric and tendencies to stoke the flames of division for political gain. Worse than Johnson, Trump has every day since the election delegitimized the results, and like Johnson he is inhibiting the peaceful transfer of power and will likely refuse to attend his successor’s inauguration in January.

Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign to rescue the soul of the nation and plainspoken empathy for working people is surely a Biden inspiration. “Grant’s 1868 campaign slogan was ‘Let Us Have Peace,’ and though in some quarters it was considered dull and flat, he genuinely wanted to reunite the country, so cruelly divided in war and then in peace,” historian Brenda Wineapple told me. “[But] Grant did not want peace at any price, nor does Biden.” In both the cases of Grant and Biden, they are determined to eradicate the scourge of hate that their predecessors enabled.

“The country having just emerged from a great rebellion,” Grant noted in his first inaugural, “many questions will come before it for settlement in the next four years which preceding administrations have never had to deal with. In meeting these it is desirable that they should be approached calmly, without prejudice, hate, or sectionalpride, remembering that the greatest good to the greatest number is the object to be attained.”

In order to recover from disunion and start anew, Grant insisted on common purpose: “This requires security of person, property, and free religious and political opinion in every part of our common country, without regard to local prejudice… All divisions—geographical, political, and religious—can join in this common sentiment.” Finally, he asked the still-beleaguered country for patience “toward another throughout the land, and a determined effort on the part of every citizen to do his share toward cementing a happy union.”

In the pursuit of this happy union, Biden is keenly aware of the political challenge of divided government and the resistance to systemic reform. In his first inaugural address in 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt encouraged resilience and a more just economic order to overcome the depression: “There must be an end to a conduct in banking and in business which too often has given to a sacred trust the likeness of callous and selfish wrongdoing. Restoration calls, however, not for changes in ethics alone. This nation asks for action, and action now.”

Roosevelt emphasized his mandate, and it’s one that Biden shares not only as the winningest popular vote-getter in American history but also as the biggest winner against an incumbent since Roosevelt himself in 1932. “The people of the United States have not failed. In their need, they have registered a mandate that they want direct, vigorous action,” Roosevelt declared. “They have asked for discipline and direction under leadership. They have made me the present instrument of their wishes.”

In this spirit, Biden should indicate, as Roosevelt reiterated, that his political foes will not prevent him from enacting his constitutional duties “that a stricken nation in the midst of a stricken world may require.” Roosevelt made clear from the outset of his administration that he would not be deterred from resolving the present crisis: “In the event that the Congress shall fail to take one of these two courses, and in the event that the national emergency is still critical, I shall not evade the clear course of duty that will then confront me.”

It may seem strange to suggest a playbook from Kennedy, the youngest president elected, for the person who will be the oldest president to serve in the White House. But it’s really not. Biden won the election by restoring the Obama coalition of young voters while fortifying a new Democratic base and moral majority — a generation of suburban families across America.

Of course, Kennedy’s January 1961 inaugural is timeless for its memorable poetry and sweep of history. Its 1,343 words are a testament to the power of precision. The Declaration of Independence was approximately 1,320 words long, and the arguably next most famous American historical document, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, was a mere 271 words. Biden would be wise to find a middle ground of length between Kennedy and Lincoln.

“In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger,” Kennedy said. “I do not shrink from this responsibility — I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation.”

It will be difficult for the American public to relate to that final sentiment amid an uncontrolled pandemic and unprecedented economic inequality. Biden, like Kennedy, wants to bring new light to a dark period. But light on its own will not be enough. Many of us yearn for a different or new age, which is what President-elect Carter envisioned in his 1977 inaugural address in the wake of the Watergate crisis.

“Let our recent mistakes bring a resurgent commitment to the basic principles of our nation, for we know that if we despise our own government we have no future,” Carter told the nation. “We recall in special times when we have stood briefly, but magnificently, united. In those times no prize was beyond our grasp.”

Carter’s call for unity was, like Biden’s, grounded in the pursuit of “competent and compassionate” government, the rule of law, and human rights and dignity. Let that be the way forward.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments