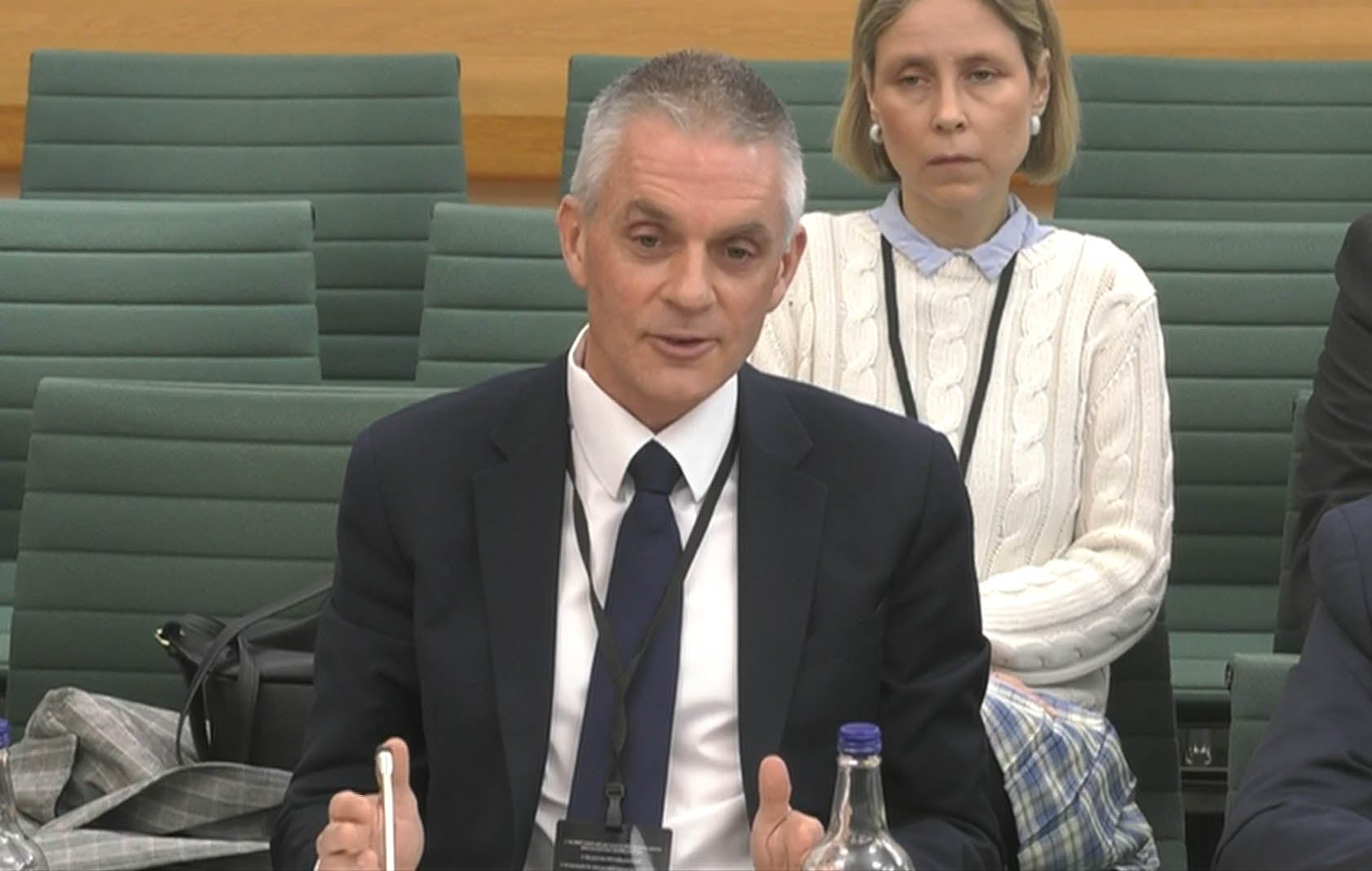

Tim Davie: People say the BBC has ‘no God-given right to exist’. As its boss, I couldn’t agree more

As director general of the corporation, you would expect me to make a case for the importance of strong, independent institutions, writes Tim Davie – but while we have a duty to resist the assaults on facts and free reporting, we can’t allow institutions like the BBC to be weaponised

What holds together strong societies and healthy democracies? Today, I find more and more conversations are gravitating towards the growing threats to the very fabric of what makes a place like the UK such a civilised place to live.

As geopolitical tensions rise and technology rapidly reshapes our world, there is a palpable sense that we are going to have to fight to preserve what we value. Solutions require longer-term choices that stretch well beyond any single political cycle. They mean not only letting the market lead the way but making deliberate choices to create the society we want.

For the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt, three main forces bind together successful democracies: strong institutions, shared stories, and social capital. Haidt argues that the current media landscape has weakened all three. It erodes social cohesion and rewards the divisive and inflammatory. It weakens political systems that are based on compromise.

We now have business models and political systems that profit from polarisation, and a burgeoning global industry of monetising offence. I say this not to criticise but simply to make the case that we should not drift to a point where only one model is allowed to dominate, at a cost to our civil discourse.

This feels particularly pressing in a record-breaking election year. Around 70 countries will go to the polls, representing half the world’s population. Meanwhile, we continue to witness serious conflict and instability in the Middle East, Ukraine, Sudan and elsewhere.

Against this backdrop, we are witnessing a growing assault on facts and free reporting. Journalism is now blocked in around 70 per cent of countries. Only 20 per cent of people now live in what are considered free countries – a proportion that halved over a decade.

In the last few years, the BBC has seen journalists expelled from countries such as Russia or China, as well as persecuted in others like Iran. We are seeing hostile states investing heavily in deploying technology as a tool for disinformation and disruption. It adds up to a critical moment of challenge for democracy worldwide.

In the UK, we rightly pride ourselves on our collective calm in the face of a storm. We have proved ourselves time and again to be resistant to the pull of extremism. Despite all the stresses and strains, free speech still thrives and the values that hold us together remain stronger than those which force us apart.

As head of the BBC, you would expect me to make a case for the importance of strong, independent institutions. But that case will never be built on a self-interested defence of those institutions in and of themselves.

Our institutions evolved to help support and nurture democracy and preserve society’s equilibrium against the pull of extremes. They act as a foundation stone in establishing trust in each other and in our country. The UK has strong institutions because we live in a strong society – and they strengthen our society in turn.

It will always be important to debate the role of these institutions and hold them to account. They are here to serve the public, not themselves, and must always be transparent and open to criticism.

But it is also vital that we never allow their independence to be weaponised, or falsely characterised as taking a position in areas of fiercely polarised debate. No institution is perfect. Every single mistake, honestly acknowledged, should not be seized on as evidence of wholesale institutional failure.

Unbalanced, unfair and overtly politicised attacks on institutions erode the very essence of what makes us so globally admired. Surely our focus should be on simultaneously championing, investing in and reforming our precious institutions instead?

For the BBC, it is only right that, as the world changes, the contribution we make to the country should change too. Our mission will always be to inform, educate and entertain everyone but we believe we can do more to respond directly to the needs of today’s society and the shared challenges we now face.

Recently, one politician stated that the BBC has no “God-given right to exist”. I agree. I know that any sense of complacency, defensiveness or arrogance leaves institutions fatally distanced from those they serve. We can only ever be as important and relevant as the positive impact we have on society.

That is why the BBC will prioritise three clear roles in the years ahead. We will pursue truth with no agenda, by reporting fearlessly and fairly. We will back the best British storytelling, by investing in homegrown talent and creativity. And we will bring people together, by connecting everyone to unmissable content.

By focusing on these three roles, and working with and alongside partners like never before, our goal is to deliver important benefits for the public, and the country as a whole, at a critical time.

It represents a choice. Not simply to follow the global market but actively to intervene, invest in and help shape the new wave of technological change for the good of all. To reinvent ourselves as a strong, thriving institution for the digital age, at the heart of a strong, thriving UK.

Tim Davie is director general of the BBC

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments