BB King: The King is gone but the thrill remains

While his death edges the birth of the blues ever closer to the pages of history, his music is a living presence

Just a few months short of what would have been his 90th birthday, Riley B King – known to the world as B B King, the planet’s best-loved and most-honoured blues artist – left this plane of existence in the wee small hours of Thursday night, asleep in his home in Las Vegas.

The King of the Blues, they called him; not to mention the Chairman of the Board of Blues Singers, the Dynamic Gentleman of the Blues and the World’s Greatest Blues Singer, among other soubriquets. His gifts as guitarist, singer and entertainer were prodigious but all were put into service as vehicles for the warmth and generosity of spirit with which he would, in public, envelop his audiences and, in private, routinely extend to fans, predecessors, peers and protégés.

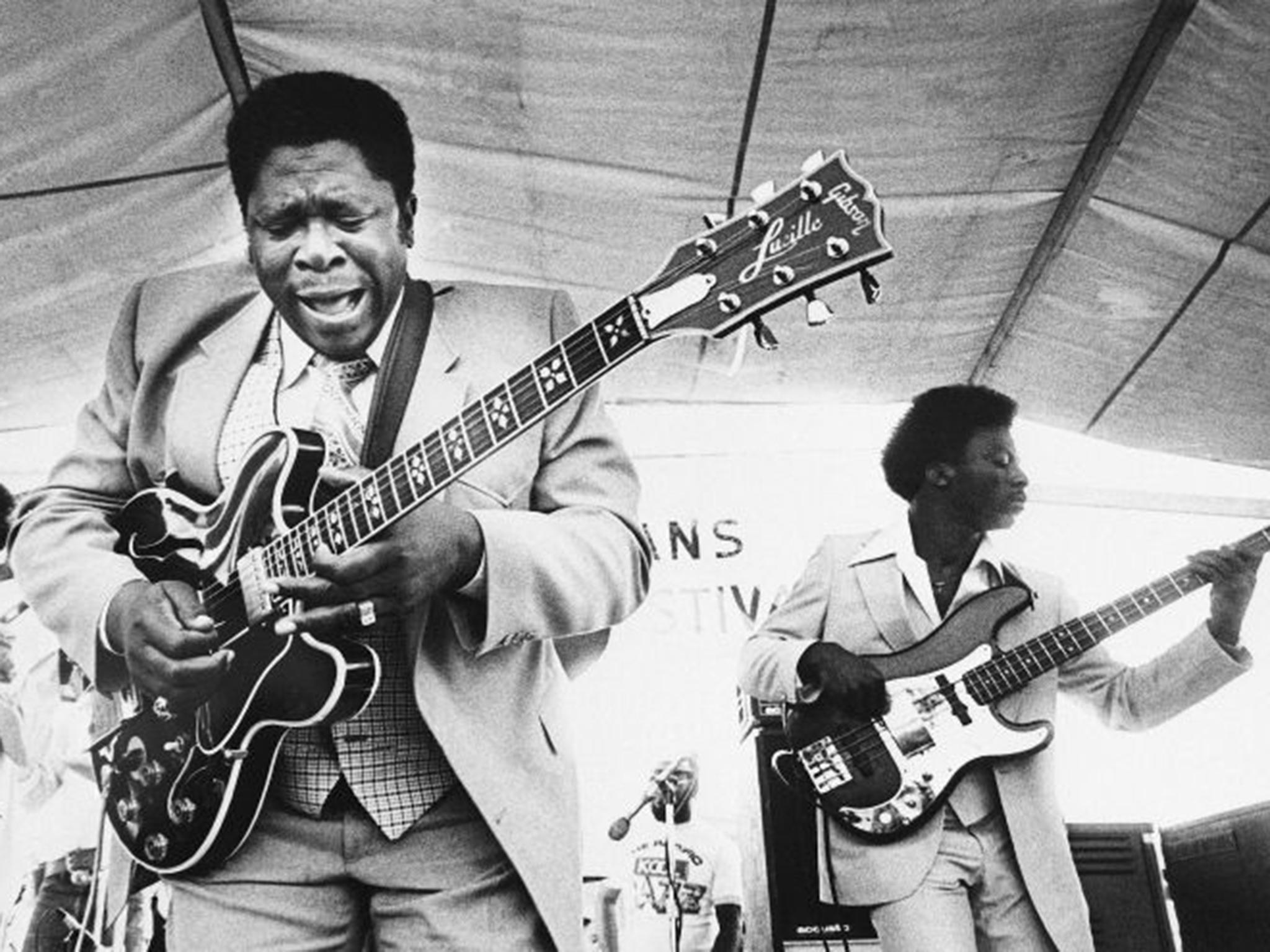

To rock fans, he was the Falstaffian patriarch with the bull-horn voice and “Lucille”, the all-singing, all-dancing guitar that stole U2’s “When Love Comes to Town” from under them. To blues fans, he was the man who wrote the book on post-war electric-blues lead guitar; who knew more ways to bend and vibrate a note than Rihanna does to undress. To the world at large, he was as beloved a popular entertainer as any master musician since Louis Armstrong: he was welcome at any concert hall in the world, up to and including the grand stage of the White House. He was a legend, a titan, a virtual demigod. To himself, though, he remained an underachiever who never believed he had properly fulfilled his artistic or commercial potential. He was proud of his achievements but simultaneously dissatisfied with them: he always insisted that he could do more, could be better.

His trajectory from the depths of the harsh racism of the Mississippi Delta to the heights of global acclaim – from white supremacy to White House, if you will – may seem to have been the archetypal Delta bluesman’s story writ large. However, B B King (the nickname is a contraction of “Beale Street Blues Boy”, his DJ handle when he broke into local radio thanks to assistance from Sonny Boy Williamson) was far from being a typical Delta bluesman in the vein of Howlin’ Wolf, Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson or John Lee Hooker. Rather, his music typified the “Memphis Synthesis”, wherein the Delta blues encountered sophisticated jazz, jump and swing played by musicians from Kansas City and the Southwest territories. Despite his admiration for his slide-slinging cousin Booker T Washington –“Bukka” – White, young Riley aspired to sophistication: his guitar style drew on jazzmen Django Reinhardt and Charlie Christian and the supremely urbane Lonnie Johnson; his bands featured horn sections rather than harmonicas and he always declared that his favourite singers were Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett.

His first record, cut in 1949, went nowhere in particular, but by 1951 he scored his first major hit, “Three O’Clock Blues”, and he was away. The road claimed him and soon he was playing more than 300 shows a year. King’s following remained almost entirely black; his music didn’t appeal to either the rock’n’roll fans of the 1950s, who embraced Chuck Berry or Bo Diddley, or to the early ’60s consensus that allowed fans of The Rolling Stones and their ilk to explore the music of rootsier types such as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf or John Lee Hooker. But in 1968 he played a triumphant show at San Francisco’s Fillmore West, and in 1970 his reworking of Roy Hawkins’ 1948 song “The Thrill is Gone” brought him into the pop charts for the first time, enchanting younger soul and pop audiences alike. From then on, there was no stopping him.

I bought my first B B King album (the 1966 live recording Blues is King, a successor to 1964’s definitive and iconic Live at the Regal and, in this listener’s opinion at least, arguably its superior) in 1968, when I was 17. The first time I saw him in person (at what was then the Brixton Sundown, now the Academy) and interviewed him, he was considerably younger than I am now: 48 to my 22. On that occasion, and in all of our subsequent encounters, he was friendly, equable, hospitable and willing to attempt to answer each and every question even when he was clearly in a state of post-show exhaustion.

“Well, this is very important to me,” he explained. “I want all my fans to know anything that they might want to know about me. Someone in this big… metropolitan… might want to know just the thing that you’re going to ask and, if that’s the case, I would like them to know.”

The last of the titans? Muddy, John Lee and the Wolf are gone, as are Ray Charles, Albert King, Freddie King, Albert Collins, Little Walter and Bo Diddley. Bobby Bland, Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Otis Rush are pretty much retired. The seat at the head of the top table now passes to Louisiana-born Buddy Guy, a mere stripling at 78, but still almost as wild and feral with guitar in hand as he was in the 1950s, with 61-year-old Robert Cray as heir apparent.

A truism, but nevertheless still true: they don’t make ’em like B B King no more. The social milieu that produced him has changed incalculably – though still not nearly enough – and the g-g-generation that drew its inspiration from the Real Guys (the generation of Eric Clapton and Johnny Winter) is itself now severely depleted, with the survivors counting the grey hairs in their beards.

Remember B B this way: “ You’re not the greatest. You’re not the only one that can do it. There are many people who can do the same thing, if not better. There’s a lotta guys out there that can do exactly what you’re doin’.

“But they can’t be you! That’s the only consolation. They can be good, they can be better, but they cannot feel what I feel. Nobody knows what I feel.”

Or, as John Lee Hooker once said, “When I die, they’ll bury the blues with me… but the blues will never die.” The King is dead. Long live the blues.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments