Making a Windrush documentary showed me how the TV industry fails Black viewers

A suit at one white-run production company who claimed to be ‘looking for diverse ideas’ scoffed: ‘No one is waiting around to hear about this, I promise you’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

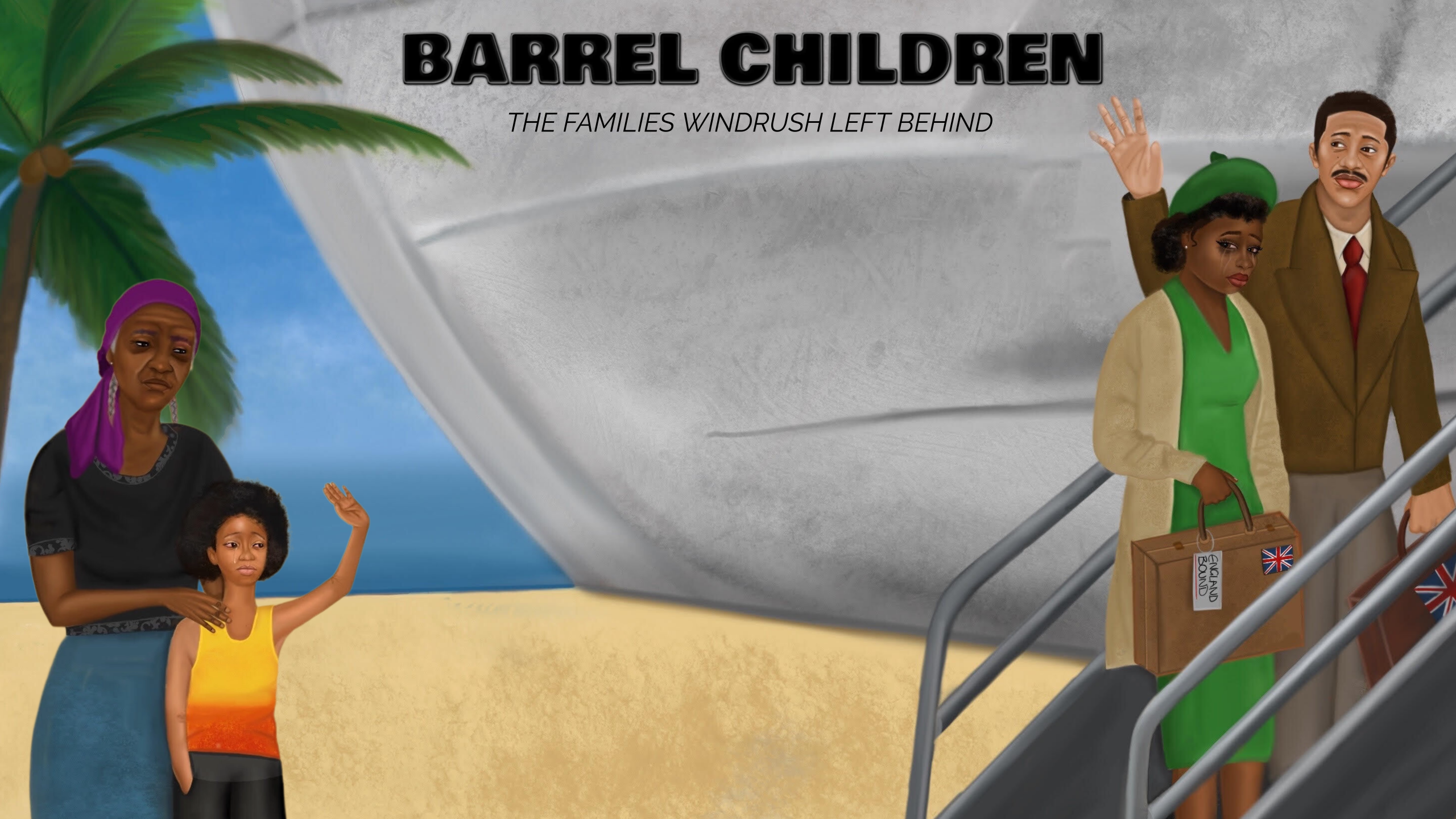

Your support makes all the difference.My documentary on “Barrel Children” has been four long years in the making. Where I hoped it would have come to fruition much earlier, this experience has given me lessons aplenty about the challenges presented to Black filmmakers.

I thought it would be wrapped within a year, but the project faced a number of setbacks; I endured numerous conversations that felt like onslaughts, where I was sharply reminded of who decides what is worthy of broadcast – and why.

A suit at one white-run production company who claimed to be “looking for diverse ideas” scoffed: “No one is waiting around to hear about this, I promise you.” But shows about penguin s**t, a random sex shop in Brighton and the most interesting toilets are considered to be riveting in Britain. Christ.

Another declared the idea of a “Barrel Children” documentary, based entirely upon Black, intergenerational experiences, “too niche”. What even is that in an increasingly multicultural society?

It’s one thing for an idea to require development or to be utterly bizarre; it’s quite another for the experiences of entire communities to be routinely dismissed, and therein lies the issue. Moreover, the resoundingly positive, transatlantic response to the Barrel Children trailer alone only serves as confirmation that there is great interest in these tales, and the suits are out of touch.

While I was always acutely aware of the lack of Black documentaries on TV, I lacked real insight into the behind-the-scenes politicking before 2018. But having contacted several production companies, broadcasters and funders, which are mostly white-run, around January of that year up until 2021 to pitch the idea, I got no joy or love.

Inspired by my late father, I set about telling the stories of children who grew up away from their biological parents in the Caribbean, raised by extended family members and then forced to move away from them. The parents of these so-called “Barrel Children”, such as my daddy, left to rebuild war-torn Britain between the 1940s and 1970s. Often, their children only knew of them through the “barrel” care packages which were sent back to their island nations.

Many were eventually “sent for” to join their parents in England. Finding themselves in strange world that made little sense to them, some children grappled with displacement after being detached from their caregivers and familiar surroundings.

The trauma that arose from these experiences of displacement and separation has spanned generations. I’ve always been cognisant of the pain it caused my dad, and I know many other families are like ours. Yet, for some reason, this hasn’t been explored a great deal on British television in recent times.

It struck me as most curious that post-Black Lives Matter, when a record number of major broadcasters and streaming platforms created schemes and pledges to increase diversity, it now appeared that some of these gatekeepers did not think this Blackety Black idea warranted airtime.

I’ve been repeatedly refused resources and funding for this project – even through initiatives described as being geared at first-time filmmakers from diverse backgrounds – along with other Black applicants I know.

Black filmmakers make up just 1 per cent of successful entrants in the world’s major competitive film festivals while Black talent is underrepresented across the industry, particularly offscreen. This is not for a lack of effort on the part of talented people.

Very few Black directors have broken through in the UK; even trailblazers such as the late Menelik Shabazz, who emerged as a self-made director in the 1980s and dedicated his life to telling our stories, attested to the systemic inequalities.

This is not all in our heads. But the system isn’t broken; worse than that, it was never actually made to facilitate our advancement in the first place.

In 2018, I set about securing footage myself and that’s what you’re watching here. I thought that if I could demonstrate how compelling these testimonies are, the bigwigs would take it seriously at some point. I didn’t want to become a household name through the production or eat well off of it – I simply wanted to tell these important stories.

At the time, I had no excess funding to approach this idea in a big way, and it initally came down to a prayer, me, my videographer cousin and his reasonable-quality camera, along with a couple of cheap lights. Over the ensuing months, we drove up and down this country from Derby and Birmingham, back to London, to the homes of “Barrel Children”, where I interviewed them about their experiences of being left behind.

These interviewees shared much of themselves, and their pain, with us – often being generous enough to cook or prepare food for us when we visited. It was warm, and that’s the thing about community.

The names of our interviewees were largely sourced through referral from personal networks, and my cousin and I were egged on by family members, friends and local community members. Of course, most people declined to be interviewed when approached because the matter is deeply personal and often uncomfortable to openly discuss.

It was a grassroots operation through and through; the likes of Patrick Vernon, Dr Elaine Arnold, reggae legend Dennis Brown’s family, broadcaster Daddy Ernie, even Jamaica’s high commissioner to the UK, Seth Ramocan, and others spoke life into us which renewed my sense of purpose and vigour, despite each callous rejection.

While some politicians and commentators often inaccurately pontificate on the supposed innate dysfunction of Caribbean-Briton people, frequently pitting us against our African-Briton counterparts and superficially highlighting disparity in our life outcomes and experiences, I’ve been keen to explore a painful aspect of shared experiences among Caribbean communities that’s too-often overlooked in this country.

The links between Empire and Windrush to “Barrel Children” and the modern experiences of Black Britons are key to understanding issues related to belonging, identity and wellbeing. However, some media executives and broadcast gatekeepers prioritise careerism over truth-telling and a commitment to public service – which is what a good documentary is all about.

At the time, I was fresh out of university, working in admin at an inner-city council to make ends meet, while juggling part-time-funded journalism school studies and writing articles for free to try break into the media industry as a news reporter.

Race and racism were the leading subject matter when a programme centred on a Black person in 2021, followed by crime and music, according to a study by the Lenny Henry Centre for Diversity at Birmingham City University.

Barrel Children sits across the intersection of history and race but wasn’t taken seriously. Sir Lenny’s research, Black In Fact, based on a study of programmes made last year, also urged broadcasters to work with Black-owned production companies, have more Black commissioners, executives and channel controllers who are also willing to “facilitate authentic storytelling”.

I’ve always been a daddy’s girl, and it’s only as I grew older that I realised that the experience of being left behind was not just his alone. As he’s no longer here to speak his truth as he used to, I’ve since strived to do that for him.

The story of Windrush has come into painfully sharp focus since 2018, but the “Barrel Children” phenomenon is less well known and all the people affected by this deserve to have their stories told.

The consequences of this displacement have been far-reaching – and unpacking this is as much about collaborative healing as it is storytelling. That’s the rub.

All in the name of Empire; after all, as far back as slavery, the formation of stable Black family relationships has been made very difficult. Enslaved Black people lived with the constant possibility of separation through the sale of one or more family members.

Thus is the deeply personal nature of these experiences, that many find it difficult to unpack the harrowing effects until this very day and examine how it has wounded and estranged relatives from one another throughout the ages.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment, sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Just prior to joining the publication, I was able to afford to work with a few professionals, such as Lisa Golden and Jack Feeney, to shoot and develop key aspects of the documentary.

When I entered into conversations with The Independent about bringing a shortened version of my production to the platform last year, I was in the middle of saving up to finish the project and screen it independently, which, at a high quality, was estimated to cost up to £100,000. I don’t have that kind of money lying around.

If we didn’t collaborate, then it would have been a much longer process which, though exciting, made me think about the many budding talented documentarians who don’t have access to any platforms at all.

When I started making this documentary, I was 25 years old with a slightly girlish optimism. I’m now approaching 30 and slightly bruised by the journey, and the knowledge that so much still needs to change.

Nadine White’s documentary ‘Barrel Children: The families Windrush left behind’ is available to watch here