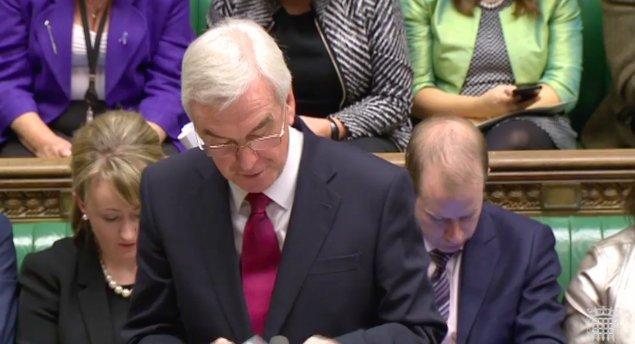

John McDonnell had a good point to make, but he made it so badly that Labour was missing in action

The same thing happened to Jeremy Corbyn at Prime Minister’s Questions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is a year since John McDonnell, the shadow Chancellor, used his first big parliamentary occasion to throw a copy of Chairman Mao’s red book across the table in the Commons chamber.

Responding to last year’s Autumn Statement, he was labouring to make a point about George Osborne’s closeness to the Chinese. As the Labour benches looked on stony-faced and disbelieving, the Chancellor picked up the book and opened it: “Oh look! It’s his personal signed copy.”

This year, McDonnell was taking no chances against Philip Hammond. Head down, he read from a prepared text that started with “the abject failure of the last six wasted years”, claimed the change in government policy “shows just how right we’ve been over the past year”, and ended by declaring: “Today we’ve seen the very people the Prime Minister promised to champion betrayed.”

He had a good point – and he made it so badly that even the members of his Labour frontbench Treasury team were glued to their phones throughout. (Which, incidentally, made me wonder about the diffusion of attention in the Commons: reading and typing on electronic devices is now the norm and creates a quite different atmosphere from the occasional backbencher doing his constituency correspondence on paper during quieter debates a few years ago.)

McDonnell rightly claimed the ban on letting agents fees as a U-turn and a victory for Labour’s campaigning. He said he was “grateful” for the saving of Wentworth Woodhouse, without even noting the paradox of spending public money on a stately home while the working poor face big cuts in tax credits. He pointed out that the improvements to the railway line between Oxford and Cambridge had been delayed from 2019. And he wasn’t wrong to say “there are no new ideas here”. But it was a lacklustre performance that failed to put Hammond under pressure.

The same thing happened to Jeremy Corbyn at Prime Minister’s Questions, minutes before the Autumn Statement. The Labour leader rose to silence from his own side and a few ironic cheers from the Conservatives. He devoted all six of his questions to the NHS and social care – all indicators point to a growing crisis about which the Autumn Statement would do nothing. But there was no grit: there was no alternative plan and nothing to dramatise Theresa May’s complacency.

Corbyn rightly challenged the Prime Minister’s claim that the Government would be spending £10bn a year more on the NHS by 2020, pointing out that the Tory-chaired Health Select Committee said it was really only £4.5bn. But then Corbyn claimed that health spending “trebled under the last Labour government”, which is just as unconvincing as May’s figure.

Perhaps it is the Brexit effect – that all of politics is absorbed by the question of how to negotiate our departure from the European Union – and Labour cannot decide whether it wants to obstruct it or influence it. The central feature of the Autumn Statement was the change to the economic forecast brought about by Brexit, and Labour knows it shouldn’t say, “We told you it was a bad idea”, but cannot quite bring itself to say, “We have better ideas for how to make this work”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments