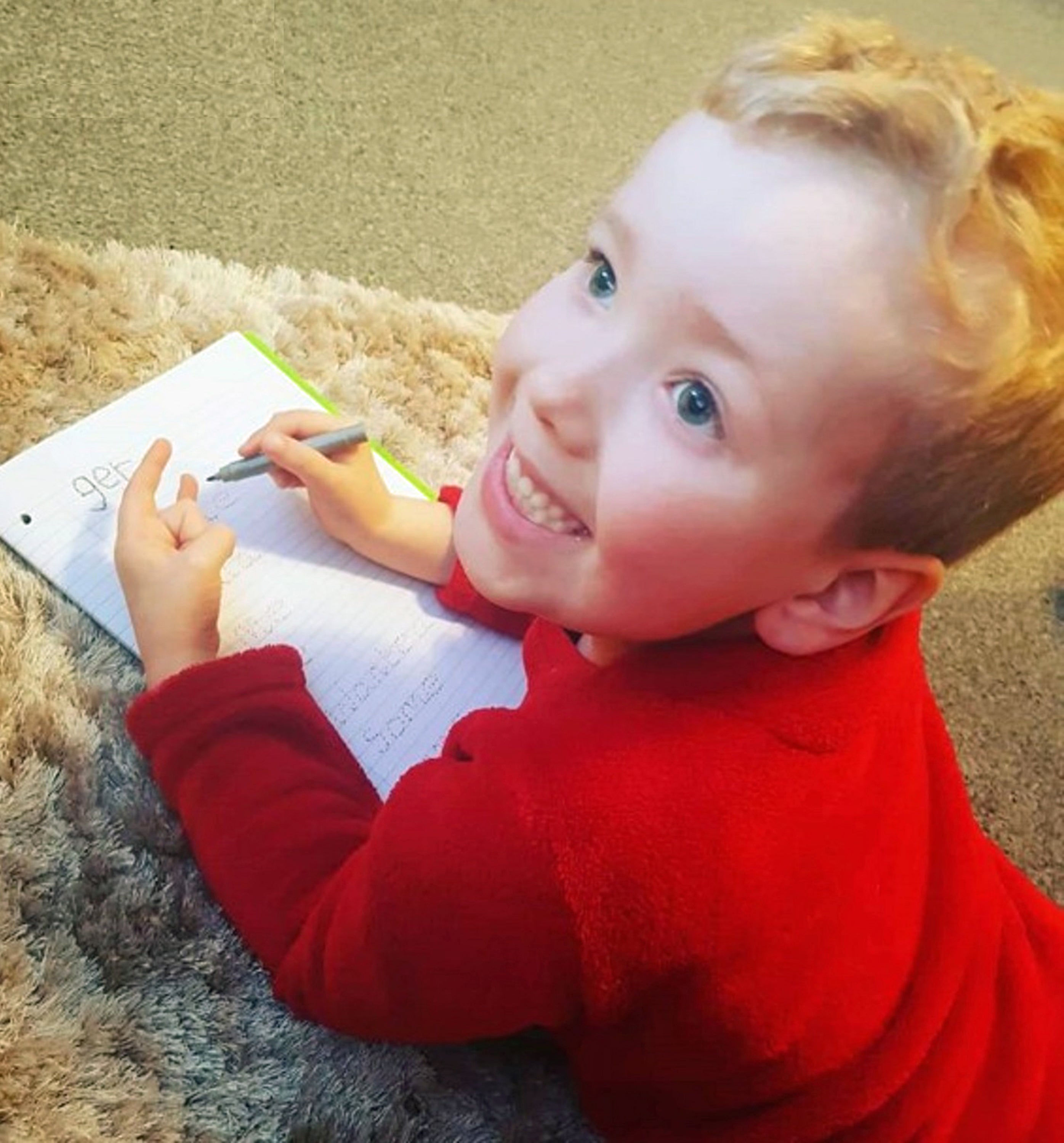

How many other children like Arthur Labinjo-Hughes are out there? We have no way of knowing

We desperately need someone to watch out for all the potential Arthurs and we are not left with much option but to ask schools to do this

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Just before the first Covid lockdown forced schools to close, a teacher got in touch with me about her concerns for what was about to happen. “Do you know who I’m most worried about,” she said. “It’s not the kids who are in the system – the ones with a designated social worker. We know who they are. It’s the kids on the edge of care. These are the ones that teachers know about, who they keep an eye on, who they make sure are OK.”

It was a haunting warning, and it has come back to me more than once in the last couple of weeks as we’ve been forced to consider the full, horrifying story of Arthur Labinjo-Hughes.

How many other Arthurs are there out there? How would we know? What can we do to find out? As always happens after these awful cases become public, we are faced with the reality that we don’t really have a handle on these questions.

And as the worried teacher who contacted me warned, this has got worse under Covid. Last week, Ofsted’s chief inspector Amanda Spielman warned of the “hokey-cokey education” that children have experienced in the last two years, including vulnerable children who “disappeared from teachers’ line of sight”.

One horrifying estimate generated by the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) suggests that some 93,000 children were mostly absent from school between September and December last year, representing more than a 50 per cent increase.

What on earth can be done about this hugely worrying number? Earlier this week, the relatively new Children’s commissioner Dame Rachel de Souza issued a call to arms, announcing a plan to use her powers to launch investigations to “locate” all so-called “ghost children” – the horrible slang now used in these circumstances – in 10 local authority areas.

Similarly. my colleague Reza Schwitzer, until recently a Department for Education civil servant working in this area, has written of the need for schools and teachers to be supported to visit every single persistently absent child at home. Reza’s plan points to a fundamental truth about schools, one that the coronavirus pandemic has brought back into stark focus: that, whether we like it or not, they are often about much more than just exam results. They are support systems for local society too. Indeed, in many places they are the only anchor institutions still standing in communities that have been ravaged by post-industrial decline and the deterioration in social fabric that followed in its wake.

Their primary function is, of course, teaching, and primarily students should attend with the overarching ambition to maximise their academic potential. And yet it is impossible to isolate this endeavour from what is going on in the streets outside the school gates and behind the closed doors of the homes to which they return every evening.

All too often too, teachers are asked to fill in where the rest of the state – withered by austerity – has withdrawn, for example in the area of youth mental health.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices newsletter by clicking here

With this in mind, the last thing I would like to do is to be seen to suggest burdening them with more demands on the already frantic lives of heads and teachers without expanding their budget and manpower in tandem. But within this reservation perhaps lies the answer. If we see Covid as a “great reset” – a chance to take stock and remember what matters most – then perhaps now is the time to think about what we ask of schools, and to invest in them accordingly.

We desperately need someone to watch out for all the potential Arthurs – and the thousands of other “ghost students” – and we are not left with much option but to ask schools to do this. But, before we do, we really must be sure that they have the resources needed to do this essential work properly.

Ed Dorrell is a director at Public First

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments