The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Today’s politicians seem more hated than ever – but Theresa May’s predecessor had it worse

A new book sheds light on the nature of the rising tide of anti-politics feeling in Britain and America

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Theresa May is useless. One of the worst politicians this country has foolishly allowed to hold high office. She has made an utter mess of Brexit and leads the weakest government ever.

That is the tone of much commentary today. And it is not surprising that people are so negative about her, really, given the rise in anti-politics sentiment in recent decades.

It seems obvious, after 2016, the year of the revolt against “politics as usual” in Britain and America, that politicians are more hated, distrusted and despised than ever before. And that this trend has been turbocharged by the rise of social media. The more sensitive commentators have, as a result, clutched their pearls and feared for the fate of democracy itself.

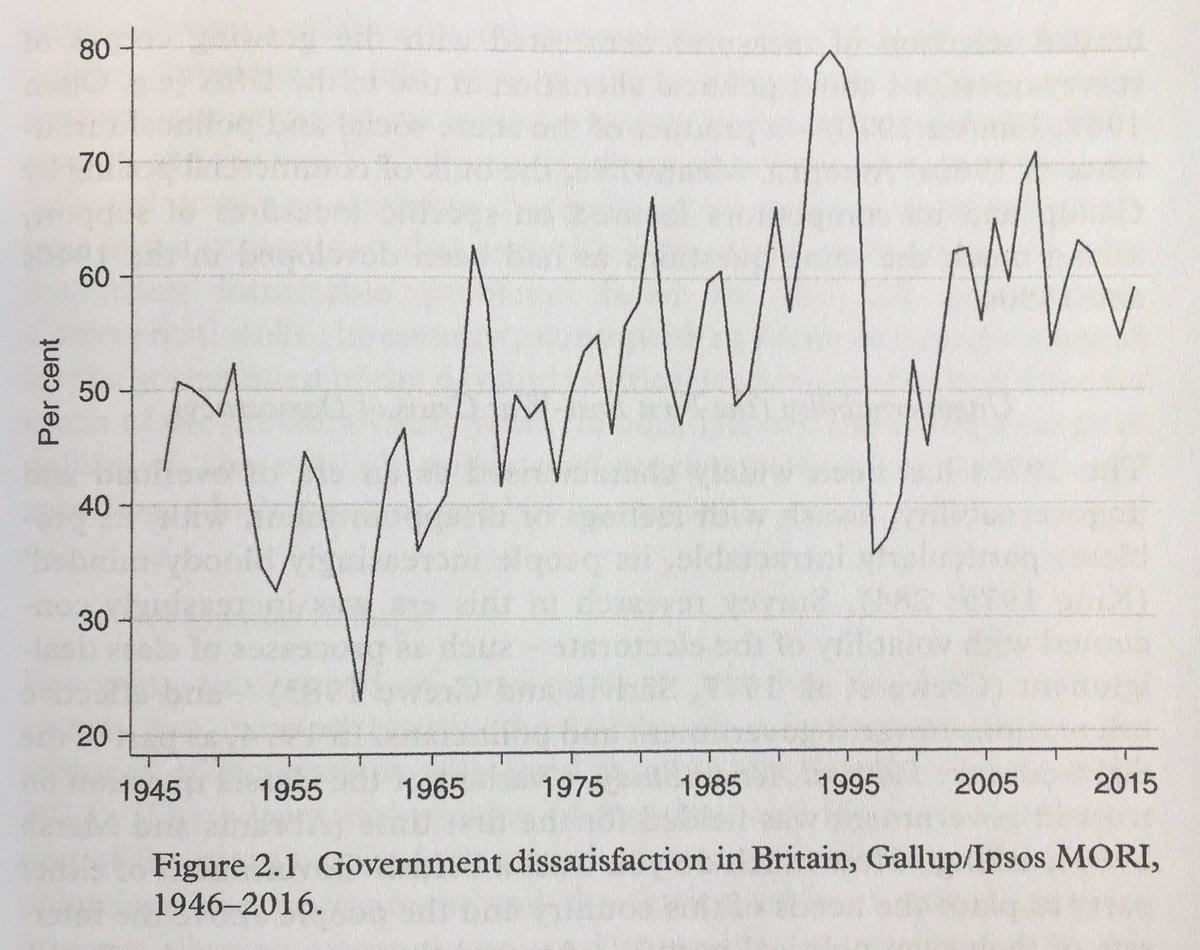

But here is a question. When do you think that the British people were most dissatisfied with the way “the government is running the country” since the war?

It was not this year. It was not during the coalition government, when everyone seemed to dislike David Cameron because of “austerity” and Nick Clegg because of tuition fees.

It was not in Gordon Brown’s time, despite the outrage over MPs’ expenses – although his personal ratings were terrible. It was not in the last years of Tony Blair, as the spiked walls of the right and the so-called left closed in on their cornered prey. It wasn’t under Thatcher, despite her presiding over 4 million unemployed. Nor Wilson or Callaghan, although they presided over strikes, inflation and decline. Nor even Heath with his three-day week or Eden at the time of Suez.

It was under John Major. His government, after the pound crashed out of the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992, was consistently the most unpopular there has ever been. In December 1994, 86 per cent of voters said they were dissatisfied with it and only 8 per cent said they were satisfied.

This puts Theresa May’s current unpopularity in perspective. Last month Ipsos Mori found 63 per cent said they were dissatisfied with her government; 30 per cent were satisfied.

It seems we have all forgotten in what low esteem we once held Sir John, last seen at the royal wedding: the much-loved hammer of hard Brexit, conscience of the Conservative Party and heroic loser who took the biggest pasting in postwar electoral history.

I came across this fact thanks to the long perspective offered by a fascinating new book about the rise of anti-politics, called The Good Politician, by Nick Clarke, Will Jennings, Jonathan Moss and Gerry Stoker.

The authors found that voters – the book is about the UK but it looks to the US too – have indeed become more suspicious of politicians, and more sceptical about politics, since the Second World War. But the process has been gradual and erratic. In Britain there was a bump up under Major and a bump down under Blair, and the nature of hostility to formal politics has changed over time.

People have always had negative attitudes to politicians, Clarke and his colleagues concluded. They have long been considered self-seeking, untrustworthy and strangers to truth. But in the 21st century they are also increasingly seen as out of touch – different from, and unsympathetic to, the mass of normal citizens. Partly, the authors argue, this is a reaction to the increasing professionalisation of politics, but partly it marks a change in expectations of “the good politician”, as one who is “not only for the people but of the people”.

In the past the good politician could be a distant, patrician leader who wanted the best for their people. Now the “ideology of intimacy” means the requirements of successful politicians are more demanding: they must be authentically in touch with “normal” life.

The book suggests that it is harder to be a good politician now because of the demands of better informed voters and unforgiving media saturation. It is worrying that people have become more negative about what the authors call the “activities and institutions required for collective and binding decision-making in plural societies” – but, they suggest, we are a long way yet from undermining the consent needed for democracy to function.

Brexit may have upset a lot of people, but it was that nice kindly John Major who came much closer to destroying democracy as we know it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments