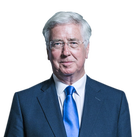

A lesson in pomposity: Michael Fallon gives several black marks to the Moser report on education

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.IT WOULD all have sounded so much better in French. By now Le Plan Moser would have been issuing forth in a stream of directives from Paris. The seven-point 'Vision' that opens the report of the National Commission on Education - 'Vision No 3: Everyone must want to learn' - would be posted at every school gate. An army of Attalis would be ready to head the new bureaucracies that the Commission proposes.

Back in 1990, I was the minister who turned down Sir Claus Moser's call for a Royal Commission on education. He set up his own unofficial version and it reported last week. We should be grateful to Sir Claus for one thing. Thanks to Baroness Thatcher, who would never set up Royal Commissions, we had forgotten their sheer awfulness. The doom-laden pomposity, the obsession with Whitehall furniture-shifting, the insistence upon comprehensive solutions, the inevitable wail for more resources.

Who now remembers the Royal Commissions of the 1960s and 1970s? Lord (Harold) Wilson chaired the fatuous Commission on the City and Financial Institutions for three years in the late 1970s. But it was the ending of the jobbers' cartel, not his recommendations, that turned the City into a leading financial centre.

Moser's team has pomposity in spades: 'We are filled with a sense of the importance of achieving the goals which we set out.' They shift some desks, too. There is to be a shiny new Department for Education and Training (in shiny new offices), a Teachers' Management Board, an Education and Training Development Authority, a Council for Innovation in Teaching and Learning, an Educational Achievement Unit, and in every town a Community Education and Training Advice Centre (Cetac).

Worse still, there will be 109 Education and Training Boards instead of local education authorities (LEAs). Just as the LEAs were withering away, with a small funding agency sending money to the schools themselves, all the local bureaucracy comes bouncing back, losing all the benefits of devolving school budgets.

Moser and his team go for comprehensive solutions with a vengeance. Nobody is allowed to opt out. They propose a new diploma, compulsory for all, in place of GCSEs and A-levels; independent schools will have to follow the national curriculum; every employer must provide five paid study days a year for all staff over 25.

There's a whole chapter on resources, concentrating almost entirely on inputs rather than outputs. They want an extra pounds 3.2bn for education spending: who wouldn't? And they are precise: our education failings can be solved for an extra pounds 375 per primary school child. Maybe, but not if we spend that as badly as the pounds 1,500 that is spent now.

The commission makes a reasonable case for universally available nursery schooling, which was endorsed by the Independent on Sunday in a leading article last week. But the case for nursery education rests on evidence that it gives children from deprived homes a better start in life. The state contribution, therefore, should be confined to issuing vouchers (to be 'spent' at a nursery school of the parents' choice) for low-income families. Let the schools themselves be promoted by a host of licensed independent providers, and not by the local council or board.

The commission's biggest weakness is that it completely ignores markets. The new Boards will repeat the dismal council monopolies. Indeed, they threaten to reverse the limited parental choice now available. 'Choice when exercised is often used to escape from the local school, working against the community school ideal,' the commission argues. To correct this, the Boards will determine a quota of 10 per cent of each school's pupils, a chilling little piece of social engineering. Why is it that in Britain we trust parents to take out five-figure mortgages on the family home or to choose which supermarket feeds their children but do not trust them to decide the school they want?

The commission condemns parental choice as having 'increased social segregation and widened differences in school performance'. They fear a 'serious danger of a hierarchy of good, adequate and sink schools emerging'. What did they think happened before? Until the government insisted on league tables of the sort published last week, only the Director of Education knew which were the sink schools. Give parents the information, give the school funding according to pupil numbers, and parents will close sink schools faster than any bureaucrat.

The commission would continue the national - or, rather, nationalised - curriculum, taking up 50 per cent of the school day for five to seven-year-olds, 70 per cent thereafter. But a prescriptive curriculum, whether laid down by ministers or by anybody else, is a nonsense in a free society in which schools are funded according to the numbers they attract.

It is time that the curriculum was handed back where it belongs - to the teachers. Government can insist that the basics are taught and tested, but leave the rest to schools to offer, parents to choose. As the commission states early on, but then forgets, 'different people are good at different things'.

By turning down Moser's plea for a Royal Commission, I privatised it. The most recent Royal Commission, on criminal justice, cost the taxpayer pounds 2,600,000. To buy this one costs you only pounds 4.99. Once again, privatisation works: even sociology finds its correct price.

The writer was Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Department of Education and Science, 1990-2.

(Photograph omitted)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments