A bittersweet Budget has acted on sugar - but not on infrastructure

I award Osborne’s Budget a tick for at least not making inequality any worse than it already is

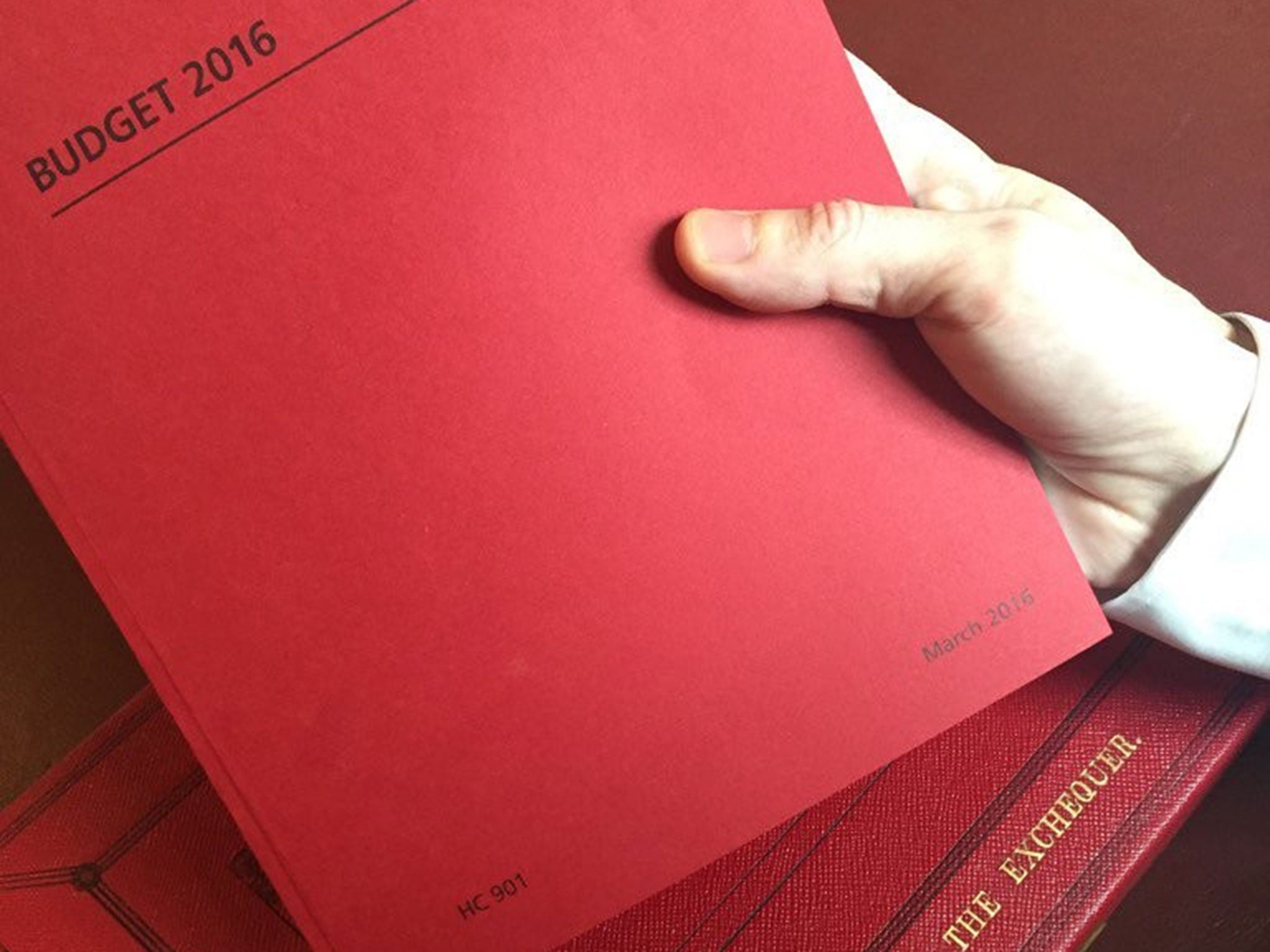

As the Chancellor of the Exchequer rose to deliver his Budget statement yesterday, I had three main concerns. Had he grasped how much the economic outlook has darkened? Would he focus on improving Britain’s infrastructure from the wretched state into which it has fallen? Would his measures further widen the yawning gap between the rich and poor?

To give Osborne his first tick of approval, I think he does get the seriousness of developments in the world economy. The problem is that economic forecasters won’t recognise this until late in the day; they can only extrapolate existing trends. That is why they failed to foresee the financial crash of 2008-9. What unnerves investors, for instance, is that with interest rates at close to zero, governments have no conventional policy measures they can employ to raise economic activity – except one, to which I shall return.

While Osborne limited himself to saying that “the outlook for the global economy is weak” and referred to “a dangerous cocktail of risks”, that was probably as far as he could go without exacerbating the pessimistic mood.

The last remaining conventional stimulus that governments can use is investment in infrastructure. On this, the Chancellor can be faulted. He sees what to do, but won’t let himself do it. Six years ago he published a National Infrastructure Plan. Last October he set up a National Infrastructure Commission headed by the vigorous Lord Adonis. And yesterday’s Budget statement promised a new four-lane road here, a tunnel road there and gave the go-ahead for Crossrail 2 in London.

But note in full what Osborne said about additional flood defences: “To respond to the increasing extreme weather events our country is facing I am today proposing a further substantial increase in flood defences. That would not be affordable within existing budgets. So I am going to increase the standard rate of Insurance Premium Tax by just half a percentage point – and commit all the extra money we raise to flood-defence spending.”

I have highlighted the critical sentence. He won’t borrow to pay for infrastructure investments, even though the British Government can currently raise funds that don’t have to be repaid for 30 years at 2.3 percent per annum.

I thought of this when the Chancellor came to a moving passage in his speech referring to sugary drinks, Osborne said that he was not prepared to look back at his time here in this Parliament, doing this job and say to his children’s generation: “I’m sorry. We knew there was a problem with sugary drinks. We knew it caused disease. But we ducked the difficult decisions and we did nothing.” Instead, he might have to say to his children’s generation: “We knew there was a problem with infrastructure. We could have borrowed long-term money at just over 2 per cent per annum to build what the nation required – but we did nothing.”

Finally inequality: most analysis is commonly done in monetary terms. Company bosses are now earning X times more than their employees; a tenth of one per cent of the population owns an enormous proportion of the nation’s wealth. And so on. But there are other forms of inequality that are just as striking.

Take life expectancy. A recent study in The Lancet revealed that people living in the richest parts of the country have a life expectancy that is eight years higher than those living in deprived areas. In fact, in his Budget speech, Mr Osborne referred to educational inequality. He said the Government was going to focus on the performance of schools in the North, where results have not been as strong as it would like. “London’s school system has been turned around; we can do the same in the North.”

Indeed, in relation to inequality, there is some good news. The further fall in unemployment is a plus factor. That we have the lowest proportion of people claiming out-of-work benefits since November 1974 is remarkable. Most of the newly created jobs are full time and most are in skilled occupations. Pay rates may be low, but pay rises, meager as they are, are actually outstripping inflation.

The steady rise in the tax-free personal allowance also helps – balanced, as of course it is under a Conservative Government, with cuts to higher rates of income tax and to capital gains tax that benefit the well-to-do. Osborne also announced a new package worth over £115m to support those who are homeless and to reduce rough sleeping. At the same time, he announced a further set of measures designed to reduce the extent to which rich people can reduce their tax bills by various forms of tax dodging.

If this appears somewhat impressionistic, fortunately the Treasury has resumed the publication of an analysis of the impact of the Budget on households. This starts by observing that changes to public spending since 2010-11 have not affected its overall distribution very much, with half of all spending on welfare and public services going to the poorest 40 percent of households. It obliquely acknowledges the cuts in welfare payments since 2010-11 by noting that support for the poor will have shifted since 2010-11 “from cash transfers through welfare, to benefits in kind from public services”. In other words, the Treasury is saying, “sorry about the cuts in welfare, but at least you have got the National Health Service and the state school system”. That isn’t much comfort.

However the highest incomes will pay more in tax in 2019-20 than the remaining 80 percent of us put together.

So I award Osborne’s Budget a tick for at least not making inequality any worse than it already is.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks