9/11 created a paradox from which we have still not managed to escape

That the ‘war on terror’ came to a nominal end with a terror attack and a cargo load of American coffins reveals again that we are stuck in a situation about which no one has a clue what to do, writes Tom Peck

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In one especially grim regard, no country has paid a higher price for the appalling events of 9/11 than the United Kingdom. Sixty-seven British people were killed that day, in what remains the single worst terrorist attack on British life. In the wars that were subsequently fought in their honour, almost 10 times that number of British military personnel have been killed – 455 in Afghanistan and 179 in Iraq.

America, unsurprisingly, has more horrifying numbers but they are in less shocking proportion. 2,605 Americans were murdered on 9/11, compared to an estimated 7,000 members of the US military who have been killed prosecuting the “war on terror”, which nominally came to an end in humiliating and violent fashion a fortnight ago.

(In another regard, the above is absurdly untrue. Iraq and Afghanistan provided precisely zero of the terrorists on 9/11, and have borne a scale of loss and devastation that is unquantifiable, but certainly runs into the hundreds of thousands of lives, almost all of them entirely innocent.)

That the 20th anniversary of 9/11 is marked by the final removal of all allied troops from Afghanistan is the saccharine moment Donald Trump wanted. A reality TV president who only ever understood politics as a reality TV show to be put on for the news channels wanted to stand under the shadow of the Manhattan skyline in front of a bank of American boys he brought back home, and to brag of a Mission Accomplished.

His successor, to his shame, found that script to his liking, though the unscripted reality is more fitting than he dare admit. That the war on terror came to a nominal end with an appalling terror attack and another cargo load of American coffins reveals again the paradox that was first revealed 20 years ago, and in which we are still stuck, and about which no one has a clue what to do.

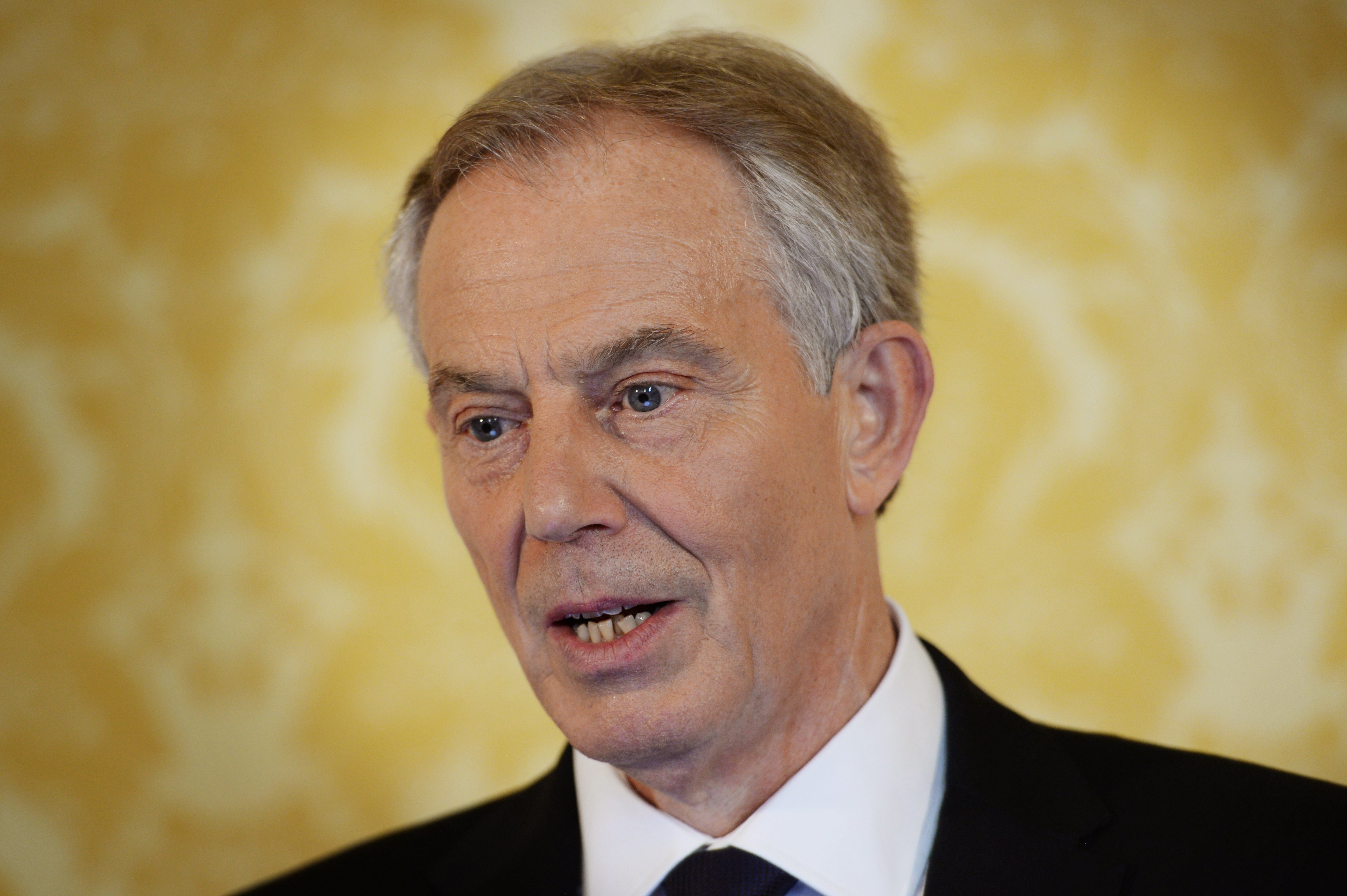

Twenty years ago, Tony Blair was in a hotel room about to give a speech to the Trades Union Congress in Brighton when he saw the same pictures on his television screen as everybody else. He has on many occasions articulated his thought processes in that moment, but perhaps did so most articulately when before the Chilcot Inquiry, nine years later. 9/11, he said, “changed the calculus of risk”.

Which it certainly did. It revealed that small gangs of committed individuals, acting more of less outside of any state or government, had the capacity to launch devastating attacks against powerful countries. But, in the ensuing weeks and years, those powerful countries found themselves unable to respond in anything other than their old ways – by waging war on other nations, and with the inevitable outcome that they would radicalise the innocent victims of those wars.

“The primary consideration for me was to send an absolutely powerful message after September 11,” Blair would tell the inquiry. “If you were a regime engaged in WMD, you had to stop.”

It is a quality of argument far below his usual standards. The attacks on 9/11 changed everything precisely because they had not been committed by a nation state, and nor had it involved the kind of weapons that only nation states can acquire. The whole point of the post 9/11 world was that the all powerful west had been undone by a network of men, operating largely independently of government. If the calculus of risk had changed, for the reasons Blair outlined, a war in Iraq was a futile response. This, precisely, is the paradox from which we have not managed to escape.

That is why it is especially important to remember the numbers of British dead, because they mark Britain’s only great material contribution. That three weeks ago, British former soldiers turned politicians like Tom Tugendhat registered their disgust at the US’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the fate to which its people have been left, also reveals Britain’s fundamental impotence and irrelevance throughout.

It is important not to conflate the two wars. One, Afghanistan, was seen as fair and just, to remove a rogue government that had given succour to a cabal of terrorists who had launched an outrageous attack. The other, Iraq, was dubious in foresight and disgraceful in hindsight.

But there is a tendency, certainly among British people, to hold Tony Blair to blame for the war in Iraq. The events of the last few weeks shed some light on that. The Iraq war was happening regardless. The only decision Blair had to make was whether or not to hold America’s hand as it did so. (One foreign correspondent, who spent a long time in both Iraq and Afghanistan, once described Britain’s role in the former as that of “the condom in the rape”. To provide an almost laughable veneer of respectability to an act of complete abhorrence.)

The primary justification for the war in Afghanistan was to prevent another 9/11 from happening again. It can’t be ignored, though it is easy to forget, that there has been no terrorist atrocity on that scale ever since. The Taliban were driven back into Pakistan, Al-Qaeda’s leaders were hunted down and killed. The hunt for Osama Bin Laden took far longer than anticipated, though, and locked the US and its allies into a degree of attempted nation building in Afghanistan that perhaps it didn’t want or expect. It certainly didn’t bother doing the same in Iraq, which was not so much an attempt to “impose our values” on others, as it is commonly described, but to flip over the monopoly board and leave them to deal with the chaos.

It is this shifting of the calculus of risk that provides the only vague justification for the British lives that have been lost, but it is itself a dubious calculation. No terrorist group has yet acquired biological or chemical weapons. It may be that a hijacked plane flown into a skyscraper is the high watermark of evil that can be achieved, and in that sense, it is hard not to conclude that hundreds of thousands of lives and trillions of dollars have done less to make the world a safer place than a series of new and irritating airline boarding procedures. In the last few days, Blair has again warned of the risks of terrorists acquiring WMDs, a sort of neat dovetailing of justification for both Iraq and Afghanistan, but for now, that justification is not real.

Blair justifications have a knack of dovetailing well. He has spent almost 20 years arguing that it was correct to preserve the special relationship, and military action in Iraq was justified in any case. This week he has again stated that, “If you distance yourself from America, it is a long way back”. It is no doubt true, but it is not all that helpful. America is unstable. As of now, we have a prime minister who has racially insulted Barack Obama to the horror of his vice president at the time, who is now president, and who also aligns himself with Ireland over Brexit. This time last year, almost the diametric opposite was true.

For 20 years, British people have argued among themselves about the rights and wrongs of the wars in which they have gladly served on the periphery but it has made precious little difference to our politics. Blair’s reputation may be ruined by Iraq but it scarcely made a dent in his career, which had another thumping election win to come, and a retirement almost at the time of his choosing (the same is true of George W Bush). There were times at which Labour was considered fortunate to have leaders that had either opposed the war, or simply not been around to vote for it, but it didn’t help Corbyn or Miliband in the slightest.

Miliband, of course, did succeed in preventing military intervention in Syria, and may even have influenced events in Washington by doing so, but the consequences of that decision leave us with a clear like for like comparison. Syria does not appear to be better off for a lack of western interference. (Another convenient argument for Blair is the thought of how Saddam Hussein would have reacted to the Arab Spring. It is convenient, but not untrue.)

Blair in 2021 is more sceptical about the ease or the moral virtue of what we still like to call exporting our values around the world. But he is right to say that when the west doesn’t act, others, principally Russia, will gladly fill the void.

There are a number of new vexations to add to the already impossible dilemma. The values of liberal democracy itself – free speech, free assembly – are currently crippling it. Authoritarian countries are using social media to spread disinformation, distrust and fragmentation within free ones, and advancing their interests in the wake of others’ retreat.

For most of the Cold War, America was able to assert and protect its values around the world principally because it achieved a degree of bipartisanship in the realm of foreign policy. Now, Trump and the party that exists in his image make politics out of it. What the UK is meant to do about that is almost liberating in its futility. It can only wait and see what happens and hope for the best.

The last few years have not been short on general elections. In all of them, the only foreign policy question that ever seems to be asked is whether or not the leader in question would fire a nuclear weapon. In 2019, The Lib Dems’ Jo Swinson answered “yes” with an almost thrilling gusto. Two weeks later she was no longer an MP.

In such absurdity, much futility is revealed. Twenty years ago, it is arguably now clear to see that an act of unparalleled barbarity steeled America and its allies for too large a fight. Three weeks later, amid a frisson of bellicose excitement, Tony Blair would tell the Labour Party conference: “This is a battle with only one outcome: our victory, not theirs.”

Another 20 years later, that has not entirely come to pass. “Our victory” is not yet forthcoming, and “we” look to be too exhausted to care.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments