Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Glencoe village is crammed with camera-toting coach parties, camper vans and day trippers. Yet above the village lies a very different world of moorland, craggy mountains, ancient forest and classical glacial valleys. Despite its murderous history, and a well-deserved reputation for bad weather, Glen Coe is the perfect choice for an uplifting walk taking in the glories of autumn.

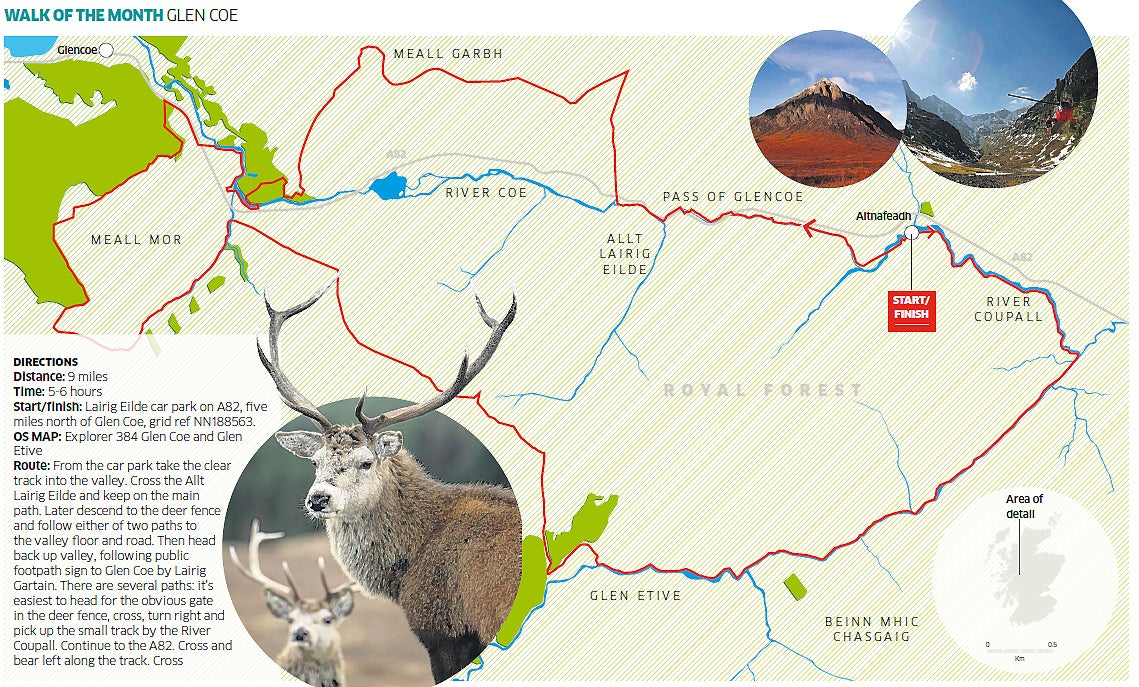

My route is straightforward if serpentine, coiling around two Munros and slithering up, over and down two perfect glacial valleys that cut south from Glen Coe. In autumn, as summer visitors melt away, the landscape assumes an atmosphere that makes the walker feel very alone.

Before setting out, I brush up on the dark deeds that tar Glen Coe's history. The 1692 massacre of the MacDonalds left 40 dead and sent hundreds more fleeing for their lives into a perishing blizzard. As I plod up the first traverse in the valley, crossing the river Allt Lairig Eilde, I don't quite feel as if I am treading on ancient bones but, zipping up my jacket against the wind, I can't fail to pick up Glen Coe's special atmosphere. The name, appropriately, is Gaelic for "Valley of Weeping".

Were that not enough to keep the imagination boggling, the route follows an old coffin trail. The medieval parish demanded any dead had to be carried over the passes to Glen Coe for burial. A stone cairn across the road from the car park is thought to be a remnant of this trail.

Huge mountains rise up, streams pouring down their flanks. Yet delightful as it is, this walk is no doddle. Ideally, you've packed gaiters and poles for this one, and it's best done anti-clockwise, heading first over Lairig Eilde. This is because the river can sometimes be in spate and impassable – if you've walked clockwise, it's an awfully long way back.

Lairig Eilde translates as "Pass of the Hinds", and Glen Coe is a prime spot for Britain's largest land mammal. The annual rutting season got under way this month and the grunt of a red stag echoing, funnelling down the valleys, is a sound you don't forget in a hurry.

The trail is lined with inexorable false summits, each coquettishly suggesting I am upon the pass before dashing expectations. Hanging, hidden valleys emerge, fingers of mist jabbing gibbet-like from their depths. The solid lump of Buachaille Etive Beag rears up to my left, its ancient bronzed rocks mantled with a patina of grasses and mosses. The mountain keeps me company for the entire walk. Its twin summits are both classified as Munros and are popular with baggers at all times of year.

Finally, I reach the top of the pass. Ahead is a head-swimmingly steep and lengthy descent – though on a good path – that slopes away to the distant valley floor of Glen Etive and a succession of dreamy lochs. I sit down and twizzle a sandwich in my hands. Coming up from the valley, part hidden by the angle of the climb, a beetroot- faced walker inadvertently springs himself upon me. He's startled and annoyed – reasonably I think – to find someone hogging the exact spot he's coveted for the past hour of sweaty ascent. "Worth the admission fee," I say brightly, by way of an ice-breaker, nodding at the view. He stares back, gives a slight but withering shake of his head and marches on.

The tramp to the valley floor is a journey of great beauty. Lonely birds of prey zip back and forward and there are glimpses of deer. I pass through a deer fence, whereupon the landscape is transformed and becomes positively tropical with lush, waist-high ferns drooping across the path.

The walk is like a bungee jump: finally reaching a paved road at the bottom of Glen Etive, I am immediately bounced back up the parallel pass of Lairig Gartain. It's a very different route, though. The name translates as "Pass of the Ticks" and, even at this time of year, it is well named: the midges here appear to have evolved into a subspecies that can drill through denim. And the track is much rougher, erratic and sometimes indistinct.

Confused by a plethora of paths, I make a dart for the deer fence, where I follow the fence line to the River Coupall and tackle the steep track. The scenery is simply sensational. I'm on a hidden path, inches from waterfalls, looking up at overhanging alders, rowan and birch trees. At times I heave myself over stones. My heart beating like the clappers, I think about the coffin trail. How often did the pallbearers tacitly agree to ditch the deceased into the deep peat and head off to a pub to synchronise their story?

At the top of the pass, I pause on a large boulder. Behind me the view swoops down the pass. Did I just walk up that? Ahead, the route is much flatter and the A82 is visible, perhaps two miles distant.

The final stretch is easier and I bounce over more huge rocks that navigate a path through the peat. It feels like a moonscape. As I arrive at the A82, a camper van tips out its occupants. They peer doubtfully down the valley before clambering back on board. As the VW's engine fades I prepare to get all romantic about the emptiness of the Highlands. Then I am forced to wait to cross the A82 by a succession of HGVs. Glen Coe never lets you settle.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

Getting there

Mark Rowe travelled by Caledonian Sleeper (08457 55 00 33; scotrail.co.uk), which serves Fort William from London Euston, via Crewe and Preston.

Staying there

He stayed at Natural Retreats’ West Highland lodge (0844 384 3166; naturalretreats.co.uk) at Tulloch Station, which offers a three-night self-catering stay from £570 (sleeps up to eight).

More information

visitscotland.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments