The Guides: Green and pleasant lanes

Betjeman's county-by-county companions were the first travel books to engage a nation of new drivers. Jack Watkins maps their appeal

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

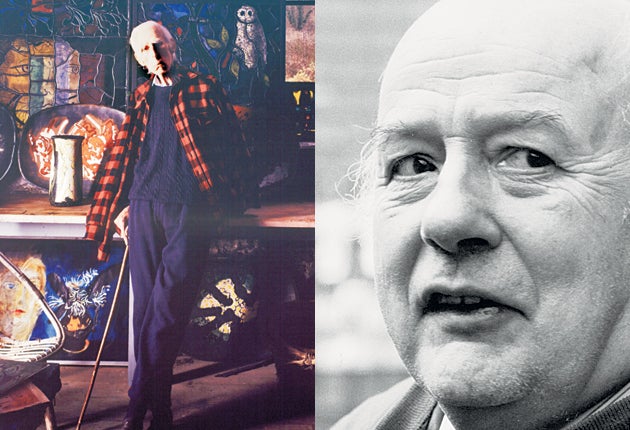

Your support makes all the difference.There have been few areas of John Betjeman and John Piper's creative lives that have not been pored over by researchers over the years, but the Shell Guides are not usually among them. The Guides, published as a series of handbooks on the British landscape between 1934 and 1984, are often dismissed as marginal to both men's work. Like a couple of classical actors slumming it in a soap, the pair's involvement in guidebook production has been viewed as a descent into naked commercialism and superficiality.

It's an interpretation that historian David Heathcote, author of the recent A Shell Eye on England, rejects, arguing that they helped shaped our modern cultural understanding of rural and non-metropolitan Britain: "The fact is that the pair involved themselves with writing and editing these books for decades, and a lot of learning and thought went into making them good. They were as serious a part of their work as Piper's paintings or Betjeman's poems."

For the last four years, Heathcote has made the Guides a subject of special study. The curator of a successful exhibition at the Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, in Hertfordshire, he's also written and presented a BBC4 documentary which, with its good humoured and Betjemanesque air of knowledge lightly worn, seemed to inhabit the Guides' creative spirit. His book can claim to be the first long study of the series, which he likens to "an early form of multimedia, part Picture Post magazine, part TV programme, but in book form".

"The Shell Guides were radical in their bold use of pictures," he explains. "Their creators grasped that the radio-listening, TV-watching masses of the 20th century needed something shallow and visual, something quickly accessible in the car and free from the long, stuffy narratives of most guidebooks of the time." In fact, for a generation of dwellers of the cities and suburbs, Shell Guides were the prime introduction to making the most of a visit to the countryside. It's a theme that seems strangely relevant once more as the National Trust rolls out its Outdoor Nation campaign, aimed at overcoming the apprehensions it says modern townies hold about rural Britain.

Heathcote believes the country versus town divide is artificial, but he can relate to the point. Growing up in south London in the 60s and 70s, his father was a civil servant who would pack the family into the Austin each year and head off for holidays in Cornwall. On arrival, the itinerary of "authentic" country experiences – Arthurian sites, ancient monuments, stately homes and cream teas – was shrewdly concocted from a Shell Guide borrowed from the local library. There's a mildly elegiac quality to Heathcote's writing in A Shell Eye on England, as he describes these British vacations "of a kind now lost in a rush to the sun by air: the Sunday drive, the weekend away, two weeks by the sea at Easter and the long drive".

Cornwall was Betjeman's favourite county too. A keen amateur botanist in his youth, he'd also become a confirmed church crawler, combining this with an ardent conservationist's predilection for Georgian and Victorian architecture. He'd nurtured the idea of a new type of guidebook for several years, before getting the go-ahead from Shell for a series aimed at the motoring "bright young things" of the period. The first Guide, by Betjeman on Cornwall, was published in 1934. It featured information on bird and plant life, local food, prehistoric Cornwall and, in what was to become a distinguishing feature of most of the Guides, an ability to find appeal in the seemingly mundane.

As an actual guide, Heathcote says it wasn't particularly good. But it sold well enough for Shell to commission more, with Betjeman's Devon Guide coming out the following year. The latter's photographs, including one of a winding, high-banked Devon lane, summed up the pleasure of travel on the open road, and the anticipation of rustic thrills ahead.

As Guides editor, Betjeman commissioned other writers, usually known to him, with mixed results. Christopher Hobhouse had participated in the Kinder Scout mass trespass of 1932, and his writing on Derbyshire (1935) conveyed a breezy love of the Peaks, and a warm fellowship with the inhabitants of the nearby metropolises of Sheffield and Manchester, who went for rambles in the hills. CHB Quennell and Peter Quennell's Somerset (1936) however, was merely windy. Its rhetoric must have floated over the heads of its intended readership and drifted off down the Avon.

Robert Byron's Wiltshire was much better, buoyed along by its travel writing author's love of antiquity and archaeology, for which there is scarcely a richer county in England. Its cover was fittingly eccentric, a Country Life meets Rodchenko montage of sheep, pigs, bee-keeping maidens, wrinkled old crones and whiskery rustics, topped by a Palladian bridge and a stately home – an indication that, even if the Guides were soft-left in sentiment, they tacitly accepted the rural social hierarchy.

Heathcote says it was the ability of the Shells to "see beauty in the quotidian detail", and to be enthusiastic even about quite ordinary places that hold the keys to their charm. "Most guidebooks today, by contrast, are only interested in places they regard as cool... dismissing vast swathes of the countryside as not worth visiting."

One of the most memorable of all the Guides is Dorset (1936) by the Surrealist artist Paul Nash, who took his commission so seriously he went to live in Swanage for a year. Nash suffered long-term shell-shock from the First World War , and found peace and solace in the countryside.

Visiting Wittenham Clumps, a pair of round-topped hills crowned by beeches, he'd sensed unease and loneliness, as well as a sense of history, and hatched the idea of "places" – areas "whose relationship of parts creates a mystery, an enchantment which cannot be analyzed... The secret of a place is there for anyone to find, though not, perhaps, to understand." In this, Nash uncovered not merely a fertile source of artistic inspiration, but the key to unlocking a true feeling for the outdoors. Heathcote says: "Nash found a language to tempt the tourist to a grassy mound by evoking the poetic."

I recently visited Heathcote at his home in Saffron Walden, an appropriate spot given that Norman Scarfe in his Shell Guide to Essex (1968) praised it as the best-looking small town in East Anglia, notable for the way it merged into the surrounding countryside. We went for a Shell-style stroll in what he jokingly calls the "Essex Heights", and for which he is campaigning to have its status raised to Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty as the "Hundred Parishes".

We followed the field edges bounding the prehistoric Icknield Way, looking over to distant views of the Fens. Heathcote pointed out farm buildings, visually appealing in a tumbledown way, a "magical" white hart in a herd of deer, and a buzzard soaring overhead. But we didn't pass another soul as we ambled along, most walkers being, as he says, "seekers of the sublime", whereas this long-tended, human-scale farmed landscape was a type much underrated. It felt to us like one of Nash's "secret places".

This relish in the "authentic" and unprimped countryside was, along with the emphasis on self-discovery, an idea Piper in particular was keen to promote in the later Guides. But it's a very different view, I'd imagine, from the one a new Outdoor Nation would expect – of special waymarked routes, interpretation boards, viewing points and, doubtless, a pricey restaurant coffee at the end of it all. Have the Shells anything to offer the new staycationers and potential country-visiting converts of today, or are they just a nostalgia fest for those with fond memories of childhood family holidays?

Heathcote thinks they do have something to offer "because they touch on the ugly, the arcane and the useful – not only the heritage beauties. None of the guides from the 1960s onwards is so out of date that they cannot be used as a Guide. In general, most of what is in them is still there. Their detailed look at quiet, remote villages and their photographs guide you to a country you might think lost as you whizz along the motorway."

I can imagine Heathcote, with his catholic tastes, and his feel for the past mingling with essentially progressive instincts, as a Shell Guide author. Unfortunately, travel guide books are notoriously unprofitable, and a Shell-like revival seems unlikely. But should any enlightened publisher be ready to give it a go, they know the man to call.

A Shell Eye on England is published by Libri Publishing (£24.92). To order a copy for the special price of £22.45 (free P&P) call Independent Books Direct on 08430 600 030, or visit www.independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments