‘Portsea’: The ‘blink and you miss it’ isle

Simon Calder spends a week visiting islands around the UK. Part 4: Portsea

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Blink and you miss it. Whether you are on the railway line that curves around to dive south, or negotiating the A3 roundabout at the eastern end of the M27, you are unlikely to register that you are about to make landfall on Britain’s most populated isle.

An Ordnance Survey report in November concluded that Portsea Island has more addresses than all the other fragments of land scattered around the UK’s shores.

I bet some of the people living at the 74,645 residences did not realise they were islanders. Because Portsea Island disguises itself as part of mainland Britain.

This is especially at low tide, when the narrow and short Portsbridge Creek amounts to barely more than a trickle through a morass of mud.

Even when the water is highest tide, the creek resembles a canal more than what it actually is: a body of sea separating Portsea from the rest of Hampshire.

An entertaining YouTube film of an inflatable boat negotiating the channel shows how little clearance the bridges have. But it is more entertaining to reach the end of the road or the railway and explore the island of surprises that most people recognise more simply as Portsmouth – for centuries, England’s window on the world.

This week, the Historic Dockyard and the Mary Rose Museum awoke after their long hibernation. Visitors in limited numbers are once again able to book online and explore the naval heritage, now that the coronavirus crisis is subsiding.

But for a perspective on this singular city, visit instead the island’s museum: from the outside looking sober, lofty and provincial, but inside feeling as though you are being let in on some intimate secrets. Much space and thought is devoted to the goalkeeper for Portsmouth’s first football team – who you may know better as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

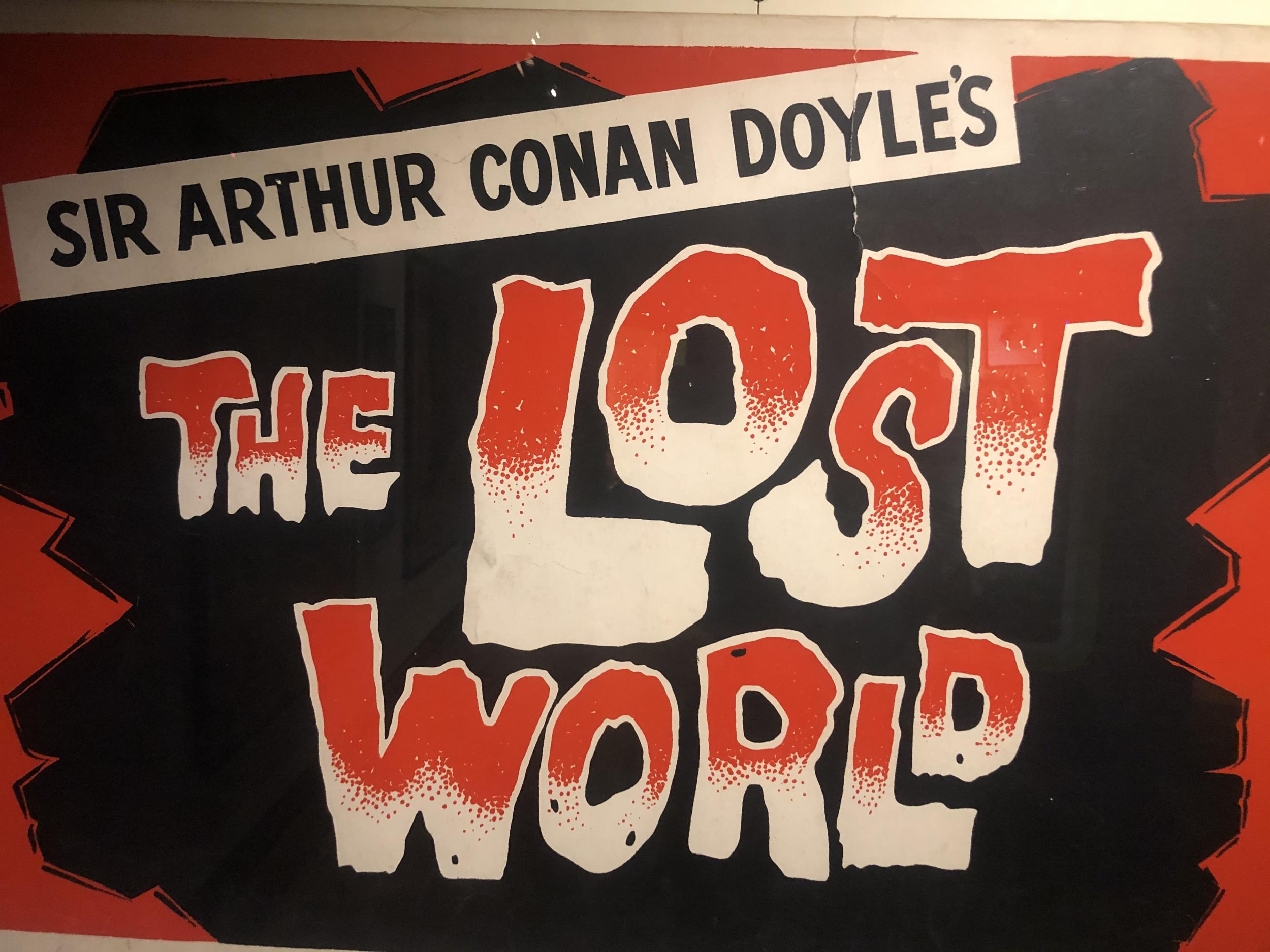

The Sherlock Holmes creator came to Portsmouth as a doctor and stayed only briefly. But another local, Richard Lancelyn Green, became the world’s greatest private collector of Conan Doyle memorabilia – and bequeathed it to the city. The collection goes well beyond the celebrated detective, and includes spectacular posters for films such as The Lost World.

“Come to Sunny Southsea where the death rate is only 9 per 1,000” may look like a message in a dystopian Covid-19 world, but was in fact a message in the Portsmouth and Southsea Official Guidebook, 1908.

The boundary between Portsmouth and Southsea, work and play, is blurred – but by the time you reach the seafront you are purely in pleasure territory. Circa 1960.

Yearning for a a rattly rollercoaster (Mad Mouse), proper Dodgems and a big wheel paying homage to the London Eye? Hungry for a “100-seat Wimpy Express fast food restaurant”? You are in the right place. With a decent sandy beach and even a stray Sixties piece of infrastructure, a hovercraft terminal, this is time travel that Conan Doyle could hardly have dreamed of.

East along the prom (built in the mid-19th century by convicts), the D-Day Story takes you back to 6 June 1944, and the planning, bloody execution and legacy of the Allied invasion of Normandy.

Even before D-Day itself, the human cost of the landings to liberate Continental Europe was immense. During exercises off the coast of Devon to prepare for the invasion, more than 700 American servicemen lost their lives.

Portsmouth itself was an inevitable target for Second World War bombing, which was followed up by inept town planning. In the middle of Old Portsmouth, the dominant structure looks as though it was rebuilt. Yet the “Cathedral of the Sea,” as it styles itself, was completed – on 12th-century foundations – only in 1991.

The city walls that protected Old Portsmouth have been lost to time, bombs and developers, but a scattering of gates and towers remain.

Beyond them lies the Point – a near-island-within-an-island. This thumb of territory, also known as Spice Island, was long known as an annexe of debauchery, patrolled by prostitutes and press-gangs.

Today it provides a good point-of-view for the Spinnaker Tower, the 560-foot-high needle (predictably sponsored by Emirates) that rises from Portsea Island.

Walk the now-salubrious streets, and as the sun dips below a miscellany of yard-arms, plan your next island escape over a drink. And reflect on an isle that has four main-line stations (accessible from Cardiff, Brighton and London); five ferry departure points; and even a hovercraft link to another island.

Portsea: gateway to the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments