Laurie Lee: Memories of the man

Jonathan Lorie reminisces with Slad locals and Lee's daughter Jessy

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

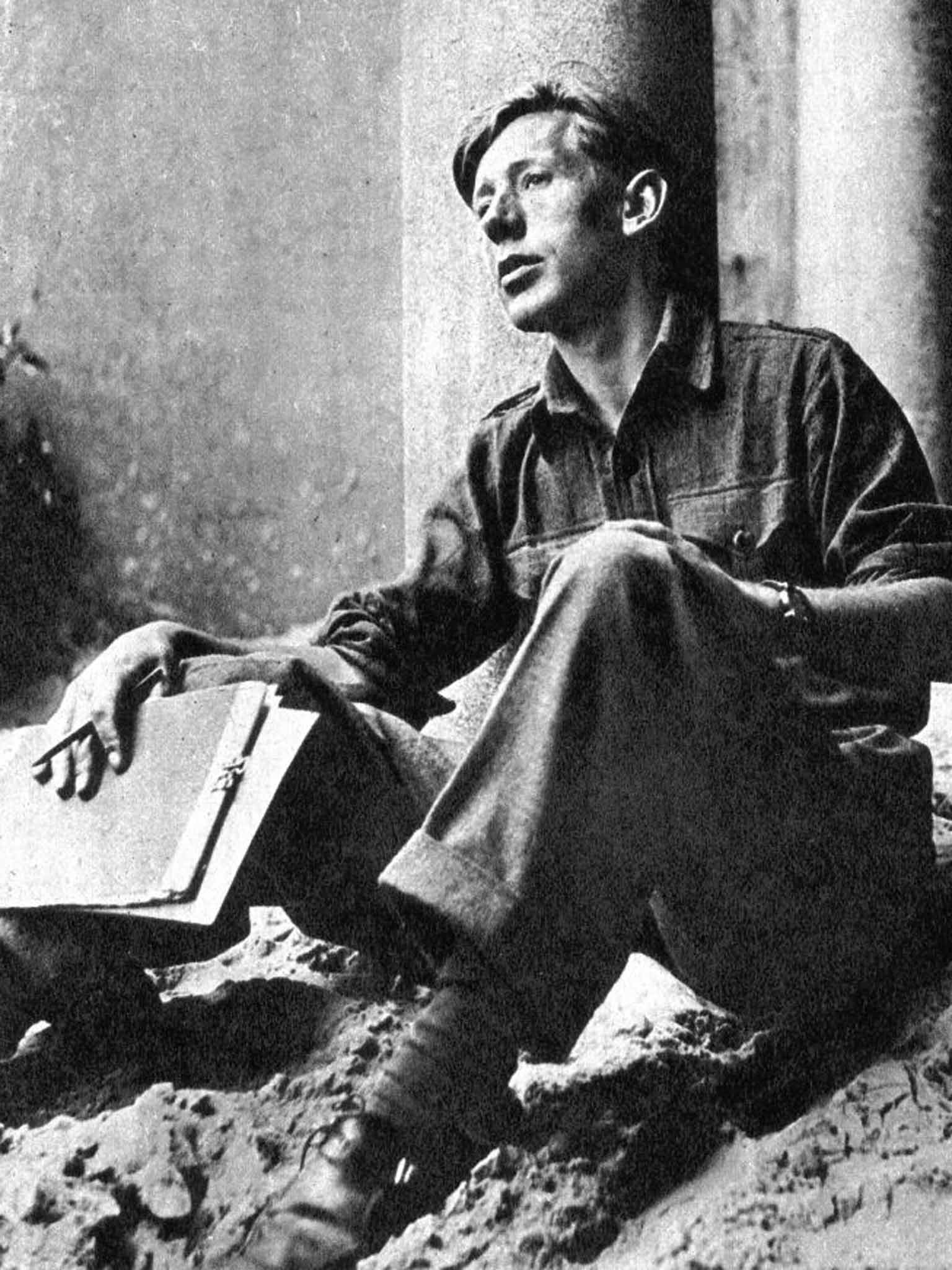

Your support makes all the difference.'My abiding impression of Laurie Lee," mused Adam, "is of him standing with his arms outstretched, a big smile on his face, a little tipsy – being roguish and charming." We were sitting on Laurie's favourite bench in Slad's Woolpack inn. Above the bar was a photo of Laurie in just such a pose. "He gave me a fiver once and said, 'Go and get drunk and write some poetry!'"

I had come to the village of Laurie Lee's childhood to meet those who remember him. Adam Horowitz is a younger poet who grew up in the valley in the 1970s and knew Laurie since then. "If you're growing up here as a writer, as we did, the landscape talks to you. Walking through it inspires poetry. It's both safe and wild. There's a continual cycle of death and life, change and decay, as any nature writer will tell you. At the heart of him, Laurie needed to be here, to reconnect. It was a grounding thing."

We ambled out into summer sunlight and Adam showed me the village. In the garden of Laurie's childhood home, a young mother was bustling around her children. I asked whether she ever thought about Laurie and his six siblings squeezed into the tiny, bleached stone cottage back in the 1920s. "Oh no," she said firmly, "not unless I've been watching the films. You don't live in the past."

The memories were still vivid up at Furners Farm, the last cider orchard in the village, where Julie Cooper sat me in her medieval kitchen and poured a glass of their home-made cider. So this was the stuff they drank back then. It was cool but fierce, like a gentle brandy. "We met the original Rosie once," she smiled, "if there was a real Rosie. About 20 years ago they brought her here for a documentary. She'd been a post-mistress in Cheltenham. She was in her seventies; she'd been to the school here. She was very sweet. But she didn't remember kissing Laurie Lee under a hay wagon."

Julie introduced me to her son, a handsome 13-year-old whose name was Laurie. As I turned to go, she said: "The kiss with Rosie happened in the second field beyond the stile. Past the old apple trees. Look out for it."

So I stumbled along there and stood on a field still laid to hay, sweeping down to the stream and the village. Laurie always said there were several Rosies, the book could have been called "Cider With Edna" or "Cider With Doreen". But whatever the truth, the setting for his delicious tale could easily have been this patch of earth.

In his essay on Writing Autobiography, Laurie said that "the only truth is what you remember". Critics have questioned how much of his famous trio of memoirs was literally true. The documentation does not exist to ever really tell. But someone who knows more than most is his daughter, Jessy, who still lives in the village.

I walked to her cottage. It had whitewashed walls and an inglenook fireplace and a garden bright with flowers. "This was my childhood home," she said, fixing me with enormous green eyes. "This is where we all lived. It was wonderful being brought up here, playing in the stream, picknicking on Swift's Hill. We were here together when he died. On a beautiful evening the sky turned totally black and a double rainbow stretched across the valley. It was extraordinary."

For the centenary she has published a book of Laurie's paintings and drawings, which she found after he died, hidden beneath a bed. "It's a homage really to Dad, because I never really thanked him." She pauses. "He did often seem tormented, which is one of the side effects of great art. But then he wrote wonderful celebratory poems about the landscape. And his prose was a long version of his poetry. I defy anyone not to get something out of his work."

There is one more memory of Laurie. I met him myself, at a poetry reading in the early 1980s. He read in a soft, heavy voice with a rich country accent, wonderful to hear. Afterwards I found him by the bar, nursing a glass of chilled white wine. "Aren't you drinking the cider?" I asked, pointing at a tray full of tumblers. "Oh no," he smiled wryly, "I don't touch it any more. You can get into trouble with that."

Getting there

The writer travelled with First Great Western (03457 000125; firstgreatwestern.co.uk) which offers advance single fares from London Paddington to Stroud from £23.30.

Staying there

The Falcon Hotel (01452 814222; falconpainswick.co.uk) in the village of Painswick has double rooms from £89, including breakfast.

Furners Farm (01452 813216; furnersfarm.co.uk) in Slad has one double room for £40, including breakfast.

Visiting there

Museum in the Park, Stratford Park, Stroud (01453 763394; museuminthepark.org.uk) will exhibit Laurie Lee's paintings from 6 September to 5 October; entry free.

Further reading

Laurie Lee: A Folio, by Jessy Lee (Unicorn Press, 24.99).

Laurie Lee: Life and Loves, by Valerie Grove (Robson Press, £12.99).

A Thousand Laurie Lees: The Centenary Celebration of a Man and a Valley by Adam Horovitz (The History Press, £12.99).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments